Back to selection

Back to selection

This Gun for Hire

Both a Cannes sensation and a hit television miniseries in France, Olivier Assayas’s Carlos, an incisive and exciting look at left-wing mercenary Ilich Ramírez Sánchez and the political culture that sustained him, now comes Stateside.

One of the wonderful things about Olivier Assayas’s sprawling new French television-produced Carlos, a picture which demands to be seen in cinemas and in its entirety, is that it observes a man who could easily be both vilified and mythologized but refuses to do either. (Carlos is most fully realized in a three film, five-and-a-half hour format, shown in marathon Cannes and New York Festival screenings; IFC will open it this fall in both full and truncated versions, and it will also play on the Sundance Channel.) Villainy and mythology are the stock and trade of contemporary politic discourse, perhaps dangerously so. To watch a mind as sharp as Assayas’s honestly navigate the thorny legacy of 1970s leftist terrorism is an exhilarating experience.

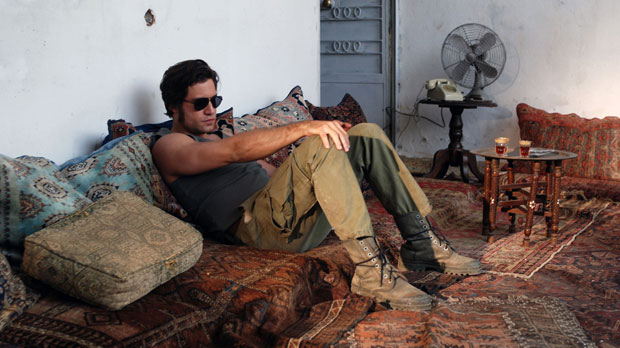

Carlos, in its intellectual freedom and engagement, is as potent and riveting as anything of its kind. The sheer mastery of craft on display combined with its grand historical and ideological sweep make Carlos the gold standard in a genre (the rise and fall of a left-wing guerrilla) that has seen more than its fair share of gems in the last decade or so (Che, The Baader Meinhof Complex, The Legend of Rita all immediately spring to mind). The two d.p.’s, Denis Lenoir (Demonlover) and Yorick le Saux (Boarding Gate), bathe scenes in golden light to contrast a palette heavy on deep blues, browns and pale greens, and the 50-something director uses his signature loose, sensual, montage-heavy style to elegantly represent the life of Ilich Ramírez Sánchez (played by Édgar Ramírez), the Venezuelan-born left-wing mercenary who was behind some of the most daring acts of political terrorism of the 1970s.

Over the course of such an exuberantly long running time, Assayas has the opportunity to create an immaculately complex tapestry of European, Middle Eastern, Asian and Latin American activists, freedom fighters, terrorists, government intelligence agents and oil ministers, most of whom maintain their fair share of secrets and double agendas. Yet he never loses touch with the romantic ideologue at the center, one whom the audience will be hard-pressed to pass swift judgment on, whose longings for human intimacy and love come smack up against his own deep moral failings, his womanizing and grandstanding, and the system of international terrorist networks and their sponsor states which uses and ultimately discards him. Whatever his Marxist ideals, Ramírez Sánchez, who lives on in prison and infamy to this day, is like many Assayas protagonists, stuck in a dehumanizing series of circumstances that are of his own doing, fighting against the binds nearly all of us are privy to: the sick and untenable game of craps that is the current system of international wealth distribution, where most are both human actors in need of livelihoods and mere commodities to be traded or disposed of.

Assayas, who is the subject of a complete retrospective at BAMcinématek this October, spoke to us about his new film on the eve of its New York Film Festival premiere.

This film takes on a historical scope and temporal size that is new to your work. In terms of the time span it covers, the various geopolitical issues that is delves into, and its extraordinary large cast of characters speaking in nearly half a dozen different languages, how did your methods have to evolve in order to pull this off? Every single film defines its own style, defines its space, defines its own language. You have your own style, of course, but then your own style [adjusts] in different ways depending on the core issue and subject matter of the movie that you’re making. I always “discover” films rather than have any kind of preconceived notions of how I’m going to film them or what they are going to look like. I hardly ever know what the film is going to look like before I’m way into it, and the film just kind of swallows me in. I think the most interesting, exciting part of the process of making Carlos is the sense that I was experimenting, and to this day, I don’t even understand how I got away with experimenting on that kind of scale. When I approached the screenplay, the way I kind of structured it, the way I wrote it, was by using mostly documentary elements. It’s extremely factual, and it tries to deal with simultaneously the broader framework of history and the individual identity of its protagonist. When I was writing it, it felt right, it had its own energy, but it was completely different in its approach than anything I had done, or anything I knew of.

How about on the business side? What was the process of getting such an ambitious film green-lit? [Making Carlos required] someone to say, “Okay” when I brought them a five-and-a-half hour film without any kind of name cast. But the reason this [could happen] was because I was within a TV framework. A TV executive said, “We’ll just trust the film.” So once I had his green light for three movies on Carlos, which I knew would be only one movie in the end, I had space to improvise, I had space to invent, space to experiment, and I was accountable to no one. I would send them the dailies once in a while, and they were extremely happy. They came to the screening and were raving about the film. So in that sense, it was a fairy-tale situation. But it was also extremely difficult — we were also making this film with much, much, much less money than we needed, so it was terribly tough.

When did you first hear of Carlos — Ilich Ramírez Sánchez? You were approached obviously by the producers with the idea of this film, yes? Well, I was a teenager in the ’70s, so I remember Carlos in the headlines. I did not know much more than anyone on the street knows. This kind of bogeyman, this kind of evil character who’d pop up once in a while and pull off these operations. I never had any illusions about modern terrorism. I really think any terrorism is basically state-sponsored, part of the geopolitical game. I never bought the revolutionary Carlos myth. But then I knew nothing about his backstory. So when I received a four-page synopsis from producer Daniel Leconte of how Carlos was arrested in Sudan, I kind of scanned it and [thought] it was not very interesting material. But all of a sudden what clicked was, “How come no one has made a movie about Carlos?” He’s such a powerful modern figure, and I was sure there must be something behind [his story]. I was sure there must be material for a film. So I called back and said, “I think you have something here — you have Carlos.” And [Daniel] told me, “If you are interested, tell me how you would handle it. Do you want me to send you our research?” I was like, “Yeah, I want to read the research.” So he sent me 100 pages, which was basically a chronology of Carlos, and when I started reading it, I realized there were more fascinating established facts about the life of Carlos than I imagined. And also, there was a coherence. It was not the silhouette [of someone] involved in different disconnected operations — it was an individual and his history [seen] through a modern view of politics. [Carlos] was a pretty extraordinary character who led a pretty extraordinary life. But through him, there were modern politics — the mixture of Secret Service work, and [political] manipulation that very few movies have managed to capture. There was a strong frenetic story that dealt with things I’ve always been interested in but never really seen completely reflected by a movie. I thought that Syriana came close to something exciting in terms of dealing with geopolitical issues, and [Carlos] gave me some energy in terms of trying to go in that direction.

One of the things that I think is so exciting about the film is how you take a tremendous number of different perspectives on various issues that we’re still living with today — the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, or the various rivalries among Middle Eastern states — and give us a glimpse into multiple points of view without endorsing any of them, or without judging the characters for their various actions. There’s something comprehensive about the way that you approached the material that is very unusual. Did you think that you would find your way into any hot water over that? Was that ever a concern of yours in the script-writing stage? I think there are two layers there. One layer is the ’70s political debate. The political debate in the ’70s was completely disconnected from reality on many levels, but still there was a level of sophisticated political reflection. People were obsessed with politics. For youngsters, it was at the center of the culture. People would be defined by the political discussions they had, even if they were using a very stereotyped language. So one part, we’re recreating the mood, we’re recreating the language, we’re recreating the way of thinking of those times, and even its complexities. The question, “Why am I not involved in this [political] struggle?” was [for people in the ’70s] an extremely relevant, extremely serious [question] dealing with much broader historical issues. So I suppose that’s one part of it. The other part is, even in terms of today, is how do you deal with the complexities of politics? Now people seem to be happy with a completely simplified notion of what politics are about, whereas I think that the modern world is growing more and more complex. Geopolitics have always been an extremely complex domain because they have to do with waging some kind of underground wars. It includes a mixture of getting information, undercover operations, over-the-cover operations and connecting the underground struggle with the broader political codes. It involves the eternal conflict in the Middle East, which is an extremely complex mosaic of different interests. And usually, the tact people have taken is let’s just simplify it so that people can make sense of what’s going on. My approach was the exact opposite. My approach was, if I don’t feel the complexity of those contradictions, ultimately I will give a faint image. I won’t really be dealing with the most fascinating, the most truthful issues of those things. So to me, the politics [portrayed] in the film were always about complexity, being true to the complexity, true to the contradictions, true to the conflicts that basically define the geopolitical game.

I know that you’re quite fond of David Fincher’s Zodiac, and watching this film, I couldn’t help but think of that film. That film is a police procedural that honestly depicts the complexity of what it’s like to search for a serial killer. It avoids the clichés and simplifications that we find in most films of that ilk. Likewise, your film avoids the simplicities that we find in films about terrorists, or films about geopolitical operators. In the screenwriting stage, how do you find your way to that complexity that you were referring to while still making the story work dramatically? It’s really interesting because I never thought of Zodiac that way, but after making Carlos, I saw it in a slightly different light. What Fincher did in Zodiac is very interesting and ultimately very similar to what I’ve been trying to do. When you create scenes based on reality, on something that has happened, you are dependent on the testimonials of witnesses, which means that you are dependent on the fragmented sections of these events. Meaning when Fincher recreates the murders, he doesn’t fantasize about the murders, he reproduces exactly what is known. And when you deal with this kind of precise recreation of reality, obviously you are in the framework of fiction because you are using actors, cameras, whatever. But you are also trying to deal with the witnesses of reality and with the strange twists and turns of how things actually do happen. They have absurd elements, or contradicting elements. You have to integrate that stuff into your filmmaking, into the way you’re telling these events. When I was writing Carlos, I was not functioning as a screenwriter. I was functioning as a researcher, as someone who was trying to find specific materials about specific moments. And once I had gathered everything I could, I kind of just cross-checked the material. And you have one part of the story, and then there’s [another] part of the story in this other book, and you have conflicting elements. So you constantly have to do a kind of police work just to make sense of what’s believable. I was not inventing — I was reconstructing, constantly. But reconstruction can only function if you have believable individuals defined by believable convictions who are specifically believable within a historical context. Who think like people would think in the ’70s and ’80s, which is obviously a different way of thinking than our own worldview in the 21st century. You obviously have to give more layers [to your characters] than what you have in police transcripts. You have to give them flesh and blood, you have to give them passions, you have to breathe life to those characters.

Ramírez Sánchez became much more of a mercenary, and a gun for hire, if you will, as his career went along. Do you think by the time he was finally caught, in the Sudan, he had essentially given up the revolutionary ideals that had pushed him into this sort of life to begin with? Or do you think he ever really truly held them? It’s interesting that the film doesn’t necessarily answer that question for us so cleanly. No, it does not, but somehow I think in that sense that there’s something universal about him. Beyond the political questions, beyond the idea of terrorism, it’s more about, how do we relate to the ideals of our youth? I kind of accept the idea that Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, before he became Carlos, was a genuine believer in the ideas of internationalism, of Communism. He was a believer, and he had convictions, and he decided to fight for his convictions. And then he was not alone. It’s the story of his whole generation. He just went further down that road, but basically he was very similar to the people of his time. [What happened to] the ideals of the ’60s or the ’70s is something that concerns a lot of people. In terms of his exact positions, I’m sure he would say that he still believed in the things that he believed in when he was a young man. But those ideals, how much do they really stick in terms of pragmatism, in terms of grown-up life, in terms of confronting them with the world and with reality? Carlos begins as a militant, but once he has run the Vienna operation for OPEC and they have frozen him out, what space is left for him, really? He has basically been thrown out of the Palestinian movement to which he has dedicated his life. And it’s not like he could move and somehow be involved with some other Palestinian groups. The Palestinian militant framework, it’s a closed circle. So he ends up just being a professional terrorist. We are talking about becoming a mercenary, but also we are talking about surviving. His involvement with the revolutionary ideal, obviously it had to move to some kind of pragmatism and adapt to the situation at the time. Gradually, when the world changes, when history changes, and there’s less and less space for these ideals, [Carlos] becomes nothing more than a mercenary. I don’t think in terms of ideals he has changed, but he’s had a hard time connecting his ideals and his actions. We could say the same of a lot of people on a smaller scale. How do we manage to adapt our ideals to the world we live in, to the reality of growing up, of raising a family, dealing with the complexities of life, and our world?

How did you settle on Édgar Ramírez for this role, and how did you help him through the challenges of playing a character over the course of well over 25 years? It was a huge undertaking for Édgar. I had a narrative of how he went for it, how simple the decision was for him, and once he’d made the decision, how powerfully he took it over. I think the most important thing I could give him was my full confidence. Sometimes I would help him to refocus this or that moment in terms of the emotions of that character, in terms of the politics of that character, in terms of the empathy or non-empathy we should have for him in this or that specific moment. I gave him all the research I could. But all that stuff is abstract because most of it just happens prior to the shoot. The actual things happen on the shoot. So the one thing you can give to an actor who has to do something this difficult and risky is the best people to work with in terms of makeup, hair, costumes. And give him all the space he needs on the set. Édgar was more than the central character in this film. He was the film. We were making a film together, and he had a complete awareness of how we were doing it, how we were approaching it. I think it was all about mutual trust.

In an interview about Boarding Gate, I asked you when you knew you were ready to shoot a scene. You replied, “I’m ready to shoot a scene exactly when I am not ready.” With its action sequences and its overall complexity, Carlos seems like a film that would have required a more formal approach to the production. I know exactly what you mean. But in Carlos, I went further than whatever we had been doing in Boarding Gate. We did not rehearse at all. We would stage these really long, complex shots without any rehearsal, meaning no tech, no rehearsal for the actors for sure, but not even rehearsal for the crew. I would explain these really long tracking shots to the crew, and we would just go from there. We decided that we had no time to try and figure out the [blocking] — we would just do it. And I would not describe the shots to the actors. The only thing I would [say] is, “This is what happens. We need this reaction shot, the [camera] stops here and there, but in the middle, react the way you would normally react. If someone bursts into the room and starts firing a machine gun into the ceiling, just react naturally.” When you’re dealing with so many characters, and such complex action, you [initially] have no idea how it will look. Often I would just not rehearse — I would shoot the scene just to know what it looks like. When you’re specifically dealing with action scenes, it’s the energy, the drive, it’s the effect of surprise the first time that gives you the most powerful moments. But once I had shot a specific action scene, I would basically watch the shot on the replay, and I would instantly understand what we were doing, which I did not exactly picture before. I would know exactly what worked, what didn’t work, and I could instantly fix it. So after the second or third take, everything would be totally in place. If I had spent an hour trying to figure things out before doing the first shot, maybe I would have arrived at more or less the same conclusion. But just going straight for it, it’s faster, more organic and much more satisfying.