Back to selection

Back to selection

“Have You Been in Jail Recently?” Chris Doyle on How to Be a Cinematic Artist

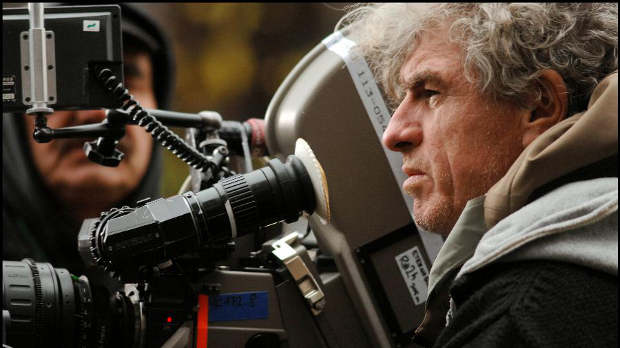

The preacher in torn blue jeans and brown suede boots sipped his pint before delivering his sermon as video projections all around flashed clips of films. The church was the open-air foyer at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in downtown Toronto, and about 60 of the faithful gathered Saturday night to hear world-renowned d.p. Chris Doyle pontificate about cinematography, aesthetics, and his alter ego, Dù Kefeng.

Last week, Dù Kefeng was one of the stars gathered to launch TIFF’s Century of Chinese Cinema summer program. The program will present the likes of action superstar Jackie Chan and heavyweight producer Nansun Shi, who will give public talks and introduce Chinese classics to Toronto audiences. Since Doyle is a white Australian, his appearance looks like a mistake, but Dù Kefeng has shot films for Zhang Yimou (Hero), Chen Kaige (also at TIFF last week) and of course Wong Kar-wai. “I’m a Chinese with a skin disease,” Doyle has often said.

TIFF invited Doyle to introduce Comrades: Almost A Love Story and Chungking Express, and to unveil a video installation called Away With Words (which recycles the title of his 1999 feature). On seven TV screens, Away With Words juxtaposes clips from In The Mood For Love, Hero, Happy Together and Ashes of Time against a new video loop that blends still photographs (i.e. “Dick Flick,” over a pile of bricks lying on the street), abstract images, bits of autobiographical data (i.e. a young Doyle studied Mandarin in Taiwan) with a split-screen of Doyle waxing in English and Dù Kefeng talking in Mandarin.

“Away With Words is a statement on cinematography,” Doyle explained earlier last week as he insisted I help him finish his tin of German lager. It was almost noon. “Away With Words is a way of dealing with words. It’s a way of getting away from words, for example taking a script or a dialogue of an actor and trying to give it the resonance or the impact or the integrity it needs.”

Doyle always carries this mindset when he handles a motion picture camera. “You see some words [in a script], and it says, ‘It’s very wet,’ or ‘It was a dry, dull day.’ How the fuck do you film a ‘dry, dull day’? So you have to get away from words. You have to find a way to give ‘a dry, dull day’ an image. That’s what cinematography’s about. It’s this balance between respect for words and giving words a resonance if they didn’t have a visual….” Here he pauses to think. “…context. That’s what cinematography’s about: making the images more than the words, and yet also being respectful to the words whether they’re spoken or written enough so that the context is clear.”

That may be so, but what can he do in the age of smartphones and the Internet where there are so many moving images? Doyle’s eyes light up. “If we actually ask people to pay for this stuff that they can get free on YouTube, then we have to do better than YouTube.” He is pleased that everybody has a camera now and that most people know what “aperture,” “F-stop” and “framing” mean. “It’s a great incentive to be better,” he declared.

Does that mean learning to do things like shoot in different formats, like 3D? Doyle shakes his head. “You get better by being a better person,” he said. “Art is what an artist makes. The point is to become an artist. It’s not to become a YouTube person.”

So, how does one become an artist? Doyle sips his beer from a coffee cup. “I like to drink. I like women.” He added that he stayed up the previous night to prepare the installation. That’s an artist. That and reading a lot or studying for a PhD in some German university. “It has to be about life. If we have something to say, it’s because we have something to say, not because we want to say something.”

Film school grads always ask him, “I wanna make films. How should I do it?” Doyle answers: “Have you been in jail recently? Have you fucked a black woman? Have you been in a car crash? If you haven’t had any of these experiences then what the fuck are you going to talk about?”

Age, experience and attitude create an artist, Doyle remarked, and he sees few artists creating today’s movies. “That’s why there are so many franchises, bceause nobody is living. Nobody is living, therefore they think filmmaking is about filmmaking. The French have told us how big a mistake that is.” Doyle laughs.

That said, Doyle admits that he’s no example for anybody. “I wouldn’t change anything in my own life, but I wouldn’t recommend it as a choice for others.” Serendipity led him from studying Chinese to eventually shooting Wong Kar-wai’s stunning string of movies in the ’90s, starting with Days of Being Wild.

At his TIFF performance, Doyle showed a clip from that 1992 classic of Leslie Cheung dancing before a mirror. “That was the greatest actor ever,” he sadly noted of the Asian James Dean who took his own life 10 years ago. That was the most touching moment in Doyle’s hour-long presentation, which veered from philosophical musings to dancing with an audience member while Latin music and pop songs echoed off the Lightbox walls. The visuals were mostly taken from his installation and added home footage of things like an elderly person hugging a tree in Beijing.

Though his performance was scripted, Doyle hurled several off-the-cuff remarks, like, “Fuck The Departed (I love you, Marty)” to rousing applause, obviously unhappy with Scorsese’s remake of Hong Kong’s Infernal Affairs that he worked on. “Asian film is like a mandala,” he said in a more serious moment. “You look at it and go further and further into it and you realize what it’s really about.” Towards the end of the free presentation, he noted, “An idea takes you somewhere special when you share it with the right people,” people like Maggie Cheung and Wong Kar-wai.

Earlier that week, that name came up when I asked him if he will work with WKW again? “You’ll see,” he said with an impish laugh.