Back to selection

Back to selection

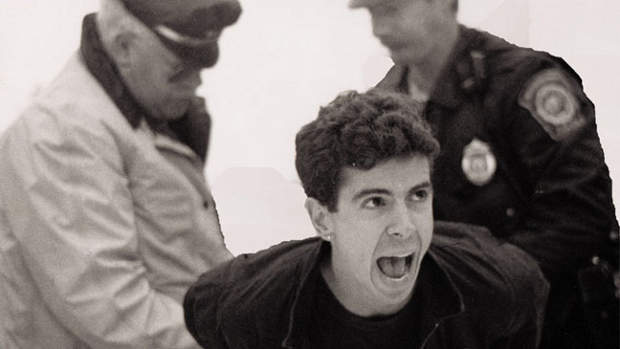

Of Time & The City

Artistry, despair and rage — the New York City of the 1980s and ’90s was defined by its fusion of these elements as artists and activists became frontline soldiers in the fight against the health crisis of AIDS. “Silence = Death” was the slogan of activist group ACT UP, an admonishment to all those who’d deny the severity of the epidemic by not taking a position. And as ACT UP members took direct action against fearful politicians, a generation of artists incorporated the movement’s anger and social critique into their own passionate work.

These New York years form the backdrop and subject in two new films, both of which premiered at Sundance 2012 and are set for theatrical release this fall. The first, Ira Sach’s Keep the Lights On, is a drama, and it’s not primarily about the AIDS crisis at all. Winner of the Teddy Award at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, it’s the story of a documentary film director, Erik (a magnetic Thure Lindhardt), and his tumultuous, decade-long relationship with a drug-addicted lawyer, Paul (Zachary Booth). But also, Sachs’ delicately etched film takes as its subject not just its characters but the years they move through. AIDS is, of course, in the backdrop, as are many other aspects of New York in these years, and the film is astute in assessing the evolution of gay identity during this time.

Director/producer David France’s debut documentary How to Survive a Plague is directly about AIDS. Comprised of rarely seen archival footage, it captures the ACT UP movement as well as another coalition, the Treatment Action Group (TAG), as they mobilize the gay community and pressure the medical establishment to devote resources to a cure. An award-winning journalist and a contributing editor at New York magazine, France brings an epic narrative sweep to this story, expertly capturing not only its public policy and science details but also the human faces of its various participants.

Filmmaker invited Sachs and France to discuss their films and themselves — how their life in New York City during these years shaped their identities as artists. Their conversation follows.

This September, Keep the Lights On is released by Music Box Films and How to Survive a Plague by IFC’s Sundance Selects.

IRA SACHS: For whatever reasons in the zeitgeist, this is a time when people are actually making films about the New York that both you and I lived in as gay people of a certain age. Why now? Why does it seem possible for us to now actually tell these stories of what it was like?

DAVID FRANCE: Well I guess the answer to that has to do with emotions and time. The traumatic plague years of AIDS were up until ’96, and we were suffering from having been through that. I think in our suffering, we stopped talking about the New York and the America that we had gone through in a way to try and allow ourselves some sort of life afterwards.

SACHS: We were in shock.

FRANCE: We were in shock, and remain in shock, I think. But there’s something about this interval of 15 years. Your film is very close to that — [set] in the late ’90s, I believe, right?

SACHS: My film begins in ’98. So, in a way, you could say there is continuity in our stories. You end your film with an afterword telling us what has happened to the people in your film. My story looks at characters who might have been involved in ACT UP, as I was, but in their private lives. In some ways, my film is the flipside of your film.

FRANCE: It’s kind of the next chapter in a way. In those [next] 15 years, we weren’t just trying to gain our footing again — we were also struggling to deal with the new reality, which was, in fact, quite shocking, that suddenly this cloud we lived under had moved on. You know, there’s a parallel in a lot of the work about the Holocaust, the films and books, in that the real thinking and processing of those ugly years started about 15 years later.

SACHS: You know, when I first started working with Mauricio Zacharias, my co-writer on this film, we talked for several months about making a film called Oh Fuck, I’m Going to Live, which was the idea of men, those who survived, starting to realize that their lives were going to continue. I think that the stories we’re telling are about the impact of AIDS and the AIDS epidemic, but they’re also about the impact of the closet in general, and the phobia that our generation grew up in. I mean, I think that’s really in a way what your film is about — fighting that culture [of phobia], you know?

FRANCE: But, they can’t be disentangled. It’s surprising to people today that as recently as the late ’80s, early ’90s, that gay people still had no role in civic life. We weren’t at the table. And it’s remarkable because of how much we control the table today. We haven’t finished this process of civil rights and integration, but the advances over the last 25 years have been so fast and remarkable — I can’t think of another community that’s made that journey in such a short amount of time. And that’s also disorienting. I mean, it’s one of the reasons why I think the trajectory of our history, this narrative line, got broken. People don’t know what happened, in part because we haven’t told them, and in part because everything has been so kind of trippy in its developments over the years. It makes last year and the year before seem like ancient history.

SACHS: Right. I think the only thing we can’t sort of forget is that so many of the people who would’ve told the stories disappeared.

FRANCE: That’s true. We lost continuity.

SACHS: We lost the people. I made a short film called Last Address. The movie was about that absence, the absence of a generation of artists, specifically, that we lost in New York, who were creating culture and then stopped creating culture due to AIDS and disappearance.

FRANCE: A beautiful film. And, you’re right. And that film shows this, this absence. It’s palpable. It’s visible.

SACHS: What’s exciting now is that there is a new interest in trying to create a presence. I think that’s what your film really does — it actually makes concrete, this form of history. You’re also clearly a storyteller. And I’m curious, as someone who came from print and magazine writing, what was it like for you to try to tell a story in a different medium and in film?

FRANCE: Well, the reason I went back to that old footage was that I knew it existed. As a journalist on the ground covering AIDS at the time, I knew that cameras were everywhere. I knew that people were buying prosumer video machinery to record what the larger culture was ignoring. And, I felt that if I went back to that footage, I could see and feel once again what it was like then in a way that maybe print [journalism] couldn’t do as strongly or as emotionally. It was a very traumatic experience to go through 700 hours of this footage, to try to remember just how dark and bad those years were. But they were also brilliant. In the midst of all of this, there was the development of the AIDS activist community as well as the social, political and medical responses to AIDS, which were an inspiration. And the America we’re enjoying today is a direct product of AIDS and AIDS activism and that period of entrenched terror, ingenuity and heroics.

SACHS: When did you move to New York?

FRANCE: I moved to New York in June 1981, about 10 days before the first New York Times piece about this mysterious ailment afflicting 41 homosexuals. I had a week of innocence. [Laughs]

SACHS: A week of fun.

FRANCE: Yeah, and it was mostly spent unpacking.

SACHS: I came to New York for the first time in the summer of ’84. So, in many ways, we lived in the same city. I’m curious, how do you feel it’s a different city now, and how do you feel it’s similar? I feel a lot of continuity to that time in terms of my interests. I’ve wound up being an activist and community organizer, and I think that development came from arriving in New York at the time when it was necessary to get involved.

FRANCE: It’s interesting — I don’t see a continuity. I moved to the East Village, which was a place of incredible artistic innovation and experimentation that was pummeled by the epidemic in the early years. It was also assaulted in a really hideous way by drugs in the ’80s. It was very exciting — which doesn’t mean that I want to go back to that time of warfare, but it was a really thrilling time with thrilling people. As the epidemic grew, I spent less time doing the nightlife of the neighborhood. My boyfriend was sick, and he was not at all sanguine about his battle with the disease. Nor was he an activist. He didn’t see a role in that for him. And so, I guess by the late ’80s I developed a kind of domestic life in the East Village, hoping in my journalism on AIDS — I’m primarily a science journalist — that I would help find the people who were doing the work that would make a difference. And who would ultimately save his life. And his life was not saved. It just didn’t come in time. And now we have lost so many of those people. We have lost the neighborhoods, and we have lost this idea that New York is the global center of a kind of creative processing of contemporary history. I miss all of that. I mean, I’m still in the East Village, and kinda stuck here, I guess, in a way.

SACHS: That’s something that’s so dramatic in your film — the sense that so much would happen too late for the individuals who could actually make the change. I mean, you’ve created a really wonderful sort of hero-building story, a myth-making story, which I think are really important for a culture.

FRANCE: And what makes it kind of even more heroic is that they were exercising agency at a time when so many more people were like Doug, my boyfriend: incapable of finding hope and just furious that this was happening to them, and paralyzed, really, by it.

SACHS: We both used the music by the composer Arthur Russell in our films. When I hear Arthur’s music in my own film, I think about the preservation of certain things about that culture that I feel are important to me. One of the things about Last Address is that it got me interested in the art of the people who were dying of AIDS in the ’80s, and they were such counterculture people. They really looked at art in a different way. I find that incredibly challenging and inspiring. Arthur was making music for himself, in a lot of ways. He was trying to make it for others, but much of the music, including the stuff that’s in both our films, was never heard during his lifetime.

FRANCE: How did you choose his work for your film?

SACHS: I saw Matt Wolf’s wonderful documentary about Arthur and his life, Wild Combination. As a filmmaker, I’m interested in defining people by their time and their history, but also through the guise of their personal story and their relationships — how they lived, how they loved. I think I was struck by the sort of human resonance of Arthur’s music. It’s so incredibly imperfect and messy and beautiful, and I thought it could be a character in the film in a certain way.

FRANCE: It’s interesting, when I saw Keep the Lights On, I felt that you interpreted his work sadly. And I see it as more celebratory, in a way.

SACHS: You know, there is a wide range of emotions, including a lot of humor, in his work. Most of it I think of as being deep and soulful more than sad. The soulfulness is the part I was looking for in my own film, which is a tough story, but I don’t think it’s a sad one necessarily.

FRANCE: It’s heartbreaking, though.

SACHS: I guess there is loss in my film, but I think there’s also growth in the story.

FRANCE: And discovery.

SACHS: I guess there’s a parallel with your film in terms of like, what we can learn from these really tragic experiences. Not to compare AIDS to a bad love affair in any way, shape or form, but I think that’s the nature of narrative. You try to make progress in the course of your story. At one point, I actually thought of calling my film two things. One was Shame, and the other was The Closet. It’s a film about life in the wake of growing up as men who learned about sex in secret and in shame, and how we’ve held onto that within our relationships and within gay culture. And I think that’s what I tried to at least bring up as a conversation, without judgment: what are the things we have learned to do as gay men communally that are no longer working for us? And I think a big question in that sense is the question of drugs. In the same way it was a fire and a fuel for the African-American community in the ’70s and ’80s, it burned through the gay community after the AIDS epidemic. And it was a mess. It was a real mess.

FRANCE: Which we’re still struggling to recover from in many areas. You know, I started on How to Survive a Plague as a direct outgrowth of an article I did for New York Magazine about one of the heroes of the epidemic in New York, Dr. Gabriel Torres, who was the first AIDS doctor to start working at St. Vincent’s. He built from within this hostile institution a world-class residential AIDS treatment facility, the first AIDS ward on the East Coast, only the second globally, and a model that was being studied and replicated throughout the world. So, ’96 comes, and the hospital emptied out. His purpose was undermined. The thing that he had spent his entire adult and professional life working on was no longer needed. And I found him just two or three years ago homeless, drug addicted, facing multiple felony charges and HIV positive himself. And so, I thought, “What happened to our heroes? What happened to this moment that should’ve been one of those signal historic moments in the gay community — not just in the gay community, but in America?” An enormous accomplishment in American history that belongs in the canon of civil rights achievements. Why didn’t we celebrate those people who did those things? Why did we let them fall like that? I think that it was largely this unprocessable grief.

SACHS: One of the things about drugs is that they are usually stronger than humans. People might begin with a certain kind of justification of usage, and then ultimately, you know, drugs tend to grab on and hold on to people in a way that is brutal.

FRANCE: Why does your character Paul fall into drugs?

SACHS: My film doesn’t go back and look at the reasons for usage; it sort of brings them up as a form of conversation. I think you start with drinking and alcoholic tendencies, and then you enter into the gay sex world, the drugs are there and it’s the very simple step. And then, I think you have lots of other histories — histories of alcoholism, of self-hatred, which I think is a central element within any drug use on some level. And then, trying to feel comfortable somewhere. Even with the negative, destructive elements of their relationship, these two men [in my film] are connected because they are in it together in some ways. That becomes a very obsessive kind of situation, but it also becomes very comfortable because at least it’s their own, and it’s something they can do together, in private and with intensity.

FRANCE: You hinted at this connection between our films, that we both have done stories about our own lives and experiences. Mine was really about people who took a different road than me, and yours was really much closer. Did you learn anything by making the film that you didn’t know already about your own past?

SACHS: Well I think by the time you’re able to tell a story [about yourself], at least for me, I’m at a point in which I both have great intimacy with the story, the subjects and the world, but also a certain amount of analytic distance. I’m able to “report,” in a certain way. In a way, I think of us as similar because, as a fiction filmmaker, I feel I’m creating a documentary of some sort of reality that I’m trying to depict. I’m trying to do that as would a social scientist, not to be too dry, but to be appropriate with my anthropology, my sociology and the sort of details of psychological life that make it real. But I think what has continued to be illuminating to me, and in a way rewarding, is how by being very specific about a personal story, I seem to trigger in a lot of people an openness about their own relationships. I’ve had a lot of people talk to me about their marriages, their relationships, their sex lives, their questions about monogamy and their questions about divorce. All these things come up when I show the film.

FRANCE: Why in the end of your film was the ultimatum so finally drawn by Paul that they are either traditionally coupled or exiled from one another? Why so black and white? Why so dichotomous?

SACHS: I think often it’s just hard to break up as it is to stay together. In this situation these men were unable to voice, perhaps, their growing recognition, that to be apart would be best for both of them.

FRANCE: So you’re saying it’s a false binary?

SACHS: It’s a false binary. Or it’s a struggle, you know? How do we separate from something that seems to become so much of ourselves? I mean, in that way, it does seem a little like your film — what do these men who connected so closely to this fight do next, when the struggle no longer becomes a thing that can keep them going?

FRANCE: That can give them life, power and purpose and energy.

SACHS: You know, both our films are in some ways about obsession.

FRANCE: Yes.

SACHS: And I think one of the reasons people get obsessed is because they want to close out the rest of the world. And you can do that in an incredibly positive way as everyone in your film has done, and you can do it in a way that’s more destructive, which is perhaps the story of my film. It’s an obsessive relationship that these men establish that cuts out the rest of the world.

FRANCE: It artificially keeps the walls of the ghetto up because it creates this nocturnal parallel universe.

SACHS: Right, right. I’ve often thought that there is a great similarity between the crack den, a church and an ACT UP meeting — they’re all places where people feel comfortable with others who are like themselves. They can feel for a moment that they don’t have to have shame, that they can drop their disguises. [Laughs] It’s very comforting to be in a group of people who think what you’re doing is right. I mean, I was in those rooms — I’m in the back left corner of almost all the images of your film, metaphorically, because I just felt at home in an ACT UP meeting. I was never a leader there, but I was arrested many times, and I experienced great comfort in that group.

FRANCE: That’s fascinating, because being in those rooms made me feel more and more cowardly.

SACHS: Why?

FRANCE: Because I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t do what they were doing. Which is why I wanted to go back and underscore the power of what they did because most people couldn’t do what they were doing.

SACHS: Can you talk a little bit more about that? So do you feel directly this film was kind of your attempt to make up for the work you had not done in the ’80s?

FRANCE: No, I don’t think so. I think I learned personal truths through it, but I don’t think I was prosecuting myself, although maybe I deserved prosecution.

SACHS: It seems like our films kind of represent who we have become as adult men, as artists, writers and storytellers, and that becoming the person who tells whatever specific story we might tell is a process. I wasn’t ready to tell the story of Keep the Lights On for 20 years, myself. It wasn’t that the events happened 20 years before, but to actually tell a film that was honest about my life and my behavior was very, very hard until it wasn’t hard.

FRANCE: And by that you mean the complicity — that both those characters were involved in this drug addiction, that it was not just one.

SACHS: The first scene of my film is a guy on a phone sex line. That wasn’t stuff that I was sharing with the world. It wasn’t even stuff I was very comfortable sharing with my therapist, to tell you the truth. What has been interesting about gay life in New York is that there was a whole world in which you were comfortable with those behaviors, but they weren’t shared outside. And that creates a lot of tension, right?

FRANCE: From the time we’re very young, we learn to practice deception and partitioning of our lives, right? And we get very good at it. We can convince people that we’re not who we seem to be. Hey, tell me about how you cast your people? Like, the actor who plays Erik.

SACHS: I had a hard time casting in America a film that was intended to be very naked in its approach, both physically and emotionally. I got a response, for example, from one agency in Hollywood who said, “No one in our agency will be available for your film.” I then heard about an actor named Thure Lindhardt, who I was told was “the bravest actor in Denmark,” which sounded good to me. I sent him the script and he auditioned by himself in a hotel room in Spain, and he chose to do all the scenes that were about people alone, about the character alone, which meant all the masturbation scenes. I sensed that he was someone who would be very comfortable with the material, as well as someone who would be very energetic as a presence on screen. My films are a lot about people who don’t make choices, characters who are struggling with taking action in his life. And it benefited the film to find an actor who was all energy and all activity. I’ve got a question for you. What were the biggest challenges in telling your story in terms of finding the narrative in what is essentially a found-footage documentary?

FRANCE: The trajectory of how the AIDS treatment activism movement goes from 1987 to 1996 is a very indirect route with an ultimate dead end in which they realize that everything they spent the last six or seven years doing was in the wrong direction, had produced catastrophic failure, and cost lives and money. And then, they had to find the proper path and get themselves onto it. And that was really tough to tell economically in such a short period of time. How to tell it in a way that actually transmitted that point to an audience, that this was a late, second act readjustment? That was tough. It was a real challenge to find the visual language to be able to do that, without resorting, as the majority of documentaries do, I guess, to somebody appearing from today on the screen to tell you the whole thing. Which would’ve been the easy way.

SACHS: One of the things that is interesting about now — that was also true then — is that people are picking up their cameras, and that they are engaged in trying to tell their stories. And I think, in that way, our films are also very similar in that we attempted to tell our stories. I know you also separate yourself from the story, but you actually make visible a story that had become invisible in a lot of ways. I think [filmmaking] and activism have kind of merged in a certain way. And that gets me back to this idea that there is something different happening right now, that there’s a kind of waking up: Our stories are valuable, they are possible to be made and there’s support for them if we look for it and if we fight for it. And there’s something extremely powerful and political about doing so when we come from a history in which are stories are not wanted.

FRANCE: I think you’re right. But I should add that I don’t consider myself an activist.

SACHS: But whether you consider yourself or not, your film is a form of activism.

FRANCE: Well my film is a story of activism, I think. And if that story sponsors and spawns future activism, I think that’s the power of the story itself. But, I think even as an almost nonparticipant in the story that I told, at least from back in that time, I needed to make sense of that time. Maybe that’s a function of where we are in our lives, that it becomes essential to look back and tell not just the story, but the meaning of the story and to situate it in the larger human context. You know, before I started working on the film, I traveled around the publishing world for years with a proposal to tell this story as a book. And I was told repeatedly that there is no market for gay stories. There is no market for AIDS stories. It’s rejected history. And I think that that’s changed. I don’t know that you and I have changed it with our films — maybe we’re just lucky to have made these films at a time when it was changing — but I think that that appraisal of the so-called marketplace is passé. I think we can hammer through that now in a way that we couldn’t before.