Back to selection

Back to selection

Director Micha X. Peled on Bitter Seeds

Monsanto, the agriculture biotech company maligned in such docs as Food, Inc. and King Corn, found renewed opposition this month with the launch of an online petition gone viral called “Tell Obama to Cease FDA Ties to Monsanto.” The petition protests the president’s 2009 appointment of the company’s former VP, Michael Taylor, to the position of senior advisor to the FDA. That this years-late call to action has inspired more than 380,000 signatures attests to the toxicity of this particular marriage between government and a multinational corporation.

If you’ll remember, Monsanto is the company that brought us DDT and Agent Orange, both of which were banned at some point for their harmful effects on people and the environment. As the world’s largest producer of genetically modified (GM) crops, the company has achieved its position through a means of strong-arm tactics, ambitious mergers, and, as the petition points out, collusions with the U.S. government.

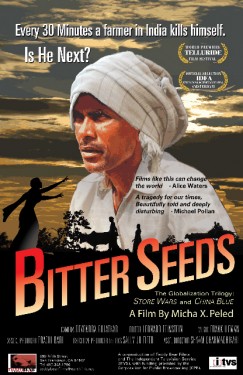

If these points don’t spark your indignation, then Bitter Seeds will. The documentary, directed by Micha X. Peled, traces Monsanto’s sizable footprint on an agrarian community in central India. The film has been traveling the festival circuit since last year, winning the “Green Screen Competition” Award at the 2011 IDFA (in a jury presided over by Joe Berlinger). After garnering acclaim at last month’s Palm Springs International Film Festival (PIFF), it is featured in the “Meet the Docs” series at the Berlin Film Festival.

Bitter Seeds sets down in remote village in the state of Maharashtra, where locally grown, renewable seeds have been phased out by genetically-modified, non-renewable seeds. In a region where the majority of farmers are rain-dependent and unable to pay for the fertilizers that GM seeds require, the influx of the new product into the marketplace has caused extreme indebtedness, leading as many as 25,000 farmers to take their lives since 1997. Bitter Seeds asks the question of whether a cotton farmer, Ram Krishna, will “be next.”

If that sounds sensational, it’s because it partly is. Contrary to the film’s conspicuous marketing, however, the documentary is among the most subtle and artful condemnations of the food industry’s Darth Vader. The film parallels two subjects: Ram Krishna, a cotton farmer struggling to pay for a dowery for his daughter; and Manjusha Amberwar, an aspiring journalist covering the farmer suicide crisis that claimed the life of her father. Micha X. Peled, an Israeli immigrant to the U.S., patiently observes Ram Krishna’s year from sowing to harvest, letting Manjusha’s journalistic process place his situation in a broader context. Where her inquiry reaches its limits, Peled picks up by interviewing a range of subjects from seed providers to environmental activists. The end result is an indictment of the agricultural biotech industry tightly wrapped within a gripping character-based narrative.

Filmmaker sat down with Micha X. Peled in Amsterdam last year to discuss the evolution of Bitter Seeds, the Indian farmer suicide crisis, and his status as an outsider living in the United States. Peled’s films are distributed through ITVS.

Filmmaker: Bitter Seeds comes after Store Wars: When Wal-Mart Comes to Town and China Blue, films that make up your Globalization Trilogy. How would you contextualize this film within that framework?

Peled: The Globalization Trilogy has three films. The first focuses on consumerism in the United States. It’s a story about Wal-Mart trying to get into a small town, and the residents of that town organizing to stop the largest retail company in the world from coming in. The second looks at how the cheap goods that Wal-Mart sells are made. So that took us to China, and it’s the story of one girl who has to leave her village to get a job, and ends up in a jeans factory where she descends into sweatshop hell. The third one takes us to the raw materials. I filmed this in India, in an area of cotton growers where their harvest gets exported to China’s garment factories where they make the jeans that Wal-Mart sells. So that’s the connection between the three. And in each step we found the globalization angle, where a Western corporation is dominating the lives of everyday people somewhere far away.

Filmmaker: Did you tackle all these projects with the theme of globalization in mind, or did they incidentally fit into that framework?

Peled: I’m primarily a storyteller. That’s where I start from. And the overall theme is globalization because I think that that is the overriding theme of our times. And unfortunately, I think that economics determine a lot of the calls that our leaders make at this day in age. As far as the particular topic goes for each of the films, I was looking for something that I didn’t know about, figuring that I would be sort of representing my audience. “If I haven’t heard of it yet, then maybe other people haven’t.”

Filmmaker: Were you familiar with the farmer suicide crisis before starting this project?

Peled: I was not. Sometimes filmmakers are lucky enough to find their next film in a film festival. And that’s what happened here. I was in the Thessaloniki International Film Festival with China Blue, and Vandana Shiva, who is a world-renowned environmental activist, was sharing a panel with me and saw my film that evening. And she said, “You should come to India for your third one.” And I told her, “Well, actually that’s kind of what I had in mind. But what do you got?” And she said, “The farmer suicide crisis. Every 30 minutes a farmer kills himself.” And I thought she must be exaggerating, because I had never heard of it. So I started investigating it, and I asked her, “What’s the globalization angle?” And she told me, “It’s because of the seeds that Monsanto sells.” And three months later I went to India, and she made the arrangements for me to meet people and start traveling around.

Filmmaker: How did you come across your subjects, Ram Krishna and Manjusha Amberwar?

Peled: I was looking for a farmer’s daughter who would be bright and energetic and an interesting subject for a film before I was looking for the farmer himself. I figured that the farmer probably wasn’t going to be able to carry an entire film on his shoulders, because they struck me as taciturn and often depressed. So I was going to a lot of high schools to meet with the female students of the graduating class, because I knew that in a few months they would be marriage candidates, and I was already aware that many of the farmers commit suicide because they cannot afford to marry off their daughters. And when I would find [students] who looked promising, I would ask to go to their villages to meet their family. That’s how we did the research. A couple weeks down the line we met Manjusha, and she said, “My dream is to become a journalist.” And I just thought, “Wow, this is precious.” And in fact, that very day we said, “Are you ready to try something on camera?” And she said, “Sure.”

Filmmaker: That must have been very fortunate for you, not just because Manjusha was like a field producer built into the narrative, but also because her quest to become a journalist provides some relief from the heavier side of the story, which is Ram Krishna’s plight.

Peled: Yeah, I definitely think I had a lot of luck. But I also feel like we create our luck.

Filmmaker: To what extent was Ram Krishna informed of your approach? Because the underlying suspense of the film—and it’s explicit in the trailer and the tagline— comes from the question, “Will he be next?” Was he aware of your general angle of the film?

Peled: He certainly wasn’t aware that I was wondering, “Will he be next?”

Filmmaker: What pretext did he think you had for pursuing the project?

Filmmaker: What pretext did he think you had for pursuing the project?

Peled: It was very simple. We just said, “We know that you farmers are suffering a great deal. So we want to understand that better and we want to tell your story to the whole world. So we’re going to be following you through entire seasons so we can see exactly what’s going on.” I think one of the challenges is that it’s hard for us to feel connected to people whose lives are so vastly different from ours. When I’m in San Francisco, it’s always hard for me to walk into a restaurant where right in front there are people begging for food or trying to make a bed for the night. That alone is difficult. So to somebody who lives on the other side of the planet, who doesn’t speak your language and who lives a different life, it’s really so much harder. So part of what I’m trying to do is humanize them. It’s easier to absorb one farmer who you spend an hour and a half with–who you see is an honorable man just trying to feed his family–than 3 million farmers who are having a hard time making a living.

Filmmaker: Beyond connecting us to an individual farmer, though, you’re also making the argument that the genetically modified seeds are contributing to the increase in suicides. Which is a hotly contested position, no?

Peled: It is a very complex issue, I agree. To put it in the simplest terms, I would say that the seeds are the main thing that has changed over the last decade or two. Yes, there are many other burdens on the farmer. For example, in the West the price of cotton is kept low because we subsidize the cotton industry so we can dump our product on the global market below the cost of production. But the main new ingredient is the seeds. And the seeds were brought in to supposedly help the farmer by reducing the cost, because they would not require pesticides. Which is plainly not true. Also, it’s plainly clear to me why these seeds are not suitable for them. To get a large crop from genetically modified seeds, you have to give the plants a lot of fertilizer and water. However, 90% of the farmers in this region do not have irrigation. They depend on the rain gods. So already, the whole concept of making genetically modified seeds that depend on a regular time table of watering and fertilizer is already wrong for this population. I don’t feel that we need to go any farther than that.

Filmmaker: Do you think the farmers are adequately informed about the requirements of the GM seeds?

Peled: My impression is that they know in general terms, but the instructions are very specific. And on top of that is the financial aspect. The idea of genetically modified agriculture is you put in more money in the beginning of the season, and because you should be getting a big harvest you should be able to more than pay back your expenses. So that requires taking loans, which requires some line of credit. 80% of these farmers cannot go to the bank because they cannot pay the bank for last year’s [loan]. So their only recourse is to go to money lenders who charge them very high interest rates. The farming costs are much higher than a corporate farm that would have a lot of credit at the bank. Already they have to bring in a higher income just to pay their expenses.

Filmmaker: One question that lingers in the film is, what happens to the surviving family members? Are the existing government subsidies effective?

Peled: There is a one-time grant or subsidy to a widow of a farmer who committed suicide because of farming difficulties. However, like everything else in India, it comes wrapped up with a few obstacles. First of all, the way they define a farmer — and it seems reasonable to us — is somebody that can prove they own a piece of land. But many of these farmers never bothered to go to the Deeds office and transfer the land from their father when it was passed to them. And some of them maybe didn’t even own their own land to begin with, maybe they worked out a deal with their neighbors. So a large number of them end up not qualifying for the loan. The other element is that there is corruption. When the farmers do qualify for a bank loan, they get a loan of, say, 20,000 rupees. It’s completely [conceivable] that the clerk who handles their loan at the bank would actually give them 19,000 rupees and keep 1,000 for himself. And [the farmers] wouldn’t dare to say anything because they assume that’s how the world turns.

Filmmaker: What can be done to remedy this issue, and how would you like your film to function within that cause?

Peled: I would be very careful to prescribe solutions, and would rather defer to organizations who have been working on these issues for a long time. I’m also very reticent to figure out solutions for other countries. I’m not qualified to say what we should do in America, but at least there I have opinions, you know? (Laughs) Part of what drives me is the fact that the company behind all of this is in the United States, and is enjoying a very privileged relationship with our government. There’s one little text point in the film that refers to the fact that [Monsanto] participated in drafting agreements between the U.S. and India. And that’s not only with India. There was a Wikileaks cable that recently showed that U.S. diplomats were working on behalf of the agriculture biotech industry in Europe, putting pressure on European countries to relax their regulations against genetically modified crops.

Also, there are ways that this story can raise awareness among American voters. For example, this coming year, there are two statewide ballot initiative campaigns to label food that has genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in it. I believe that a lot more American consumers would turn away from GMOs if they only knew that one product has it and another one doesn’t. If you decided that you don’t want to eat that stuff, then it’s easier to convince you that a farmer on the other side of the world shouldn’t be forced to use that in the first place. In this case, these happen to be cotton farmers, but this is affecting farmers in India who are growing anything else. We have to make sure that it starts with what the farmers grow. They should have other options.