Back to selection

Back to selection

Tech Talks: The FilmGate Interactive Media Festival

The 2017 FilmGate Interactive Media Festival, which took place February 3-5, was a bit different from prior editions I’ve attended. For one thing, the fest was now headquartered in the heart of Hurricanes-land — over Super Bowl weekend no less — at the University of Miami School of Communication (rather than in trendy South Beach). For another, accommodations this time included a lovely historic house rented in Coconut Grove, where I found myself one of four born-and-bred Americans, along with three other artists originally hailing from India, Serbia and Turkey. Very Real World meets virtual reality.

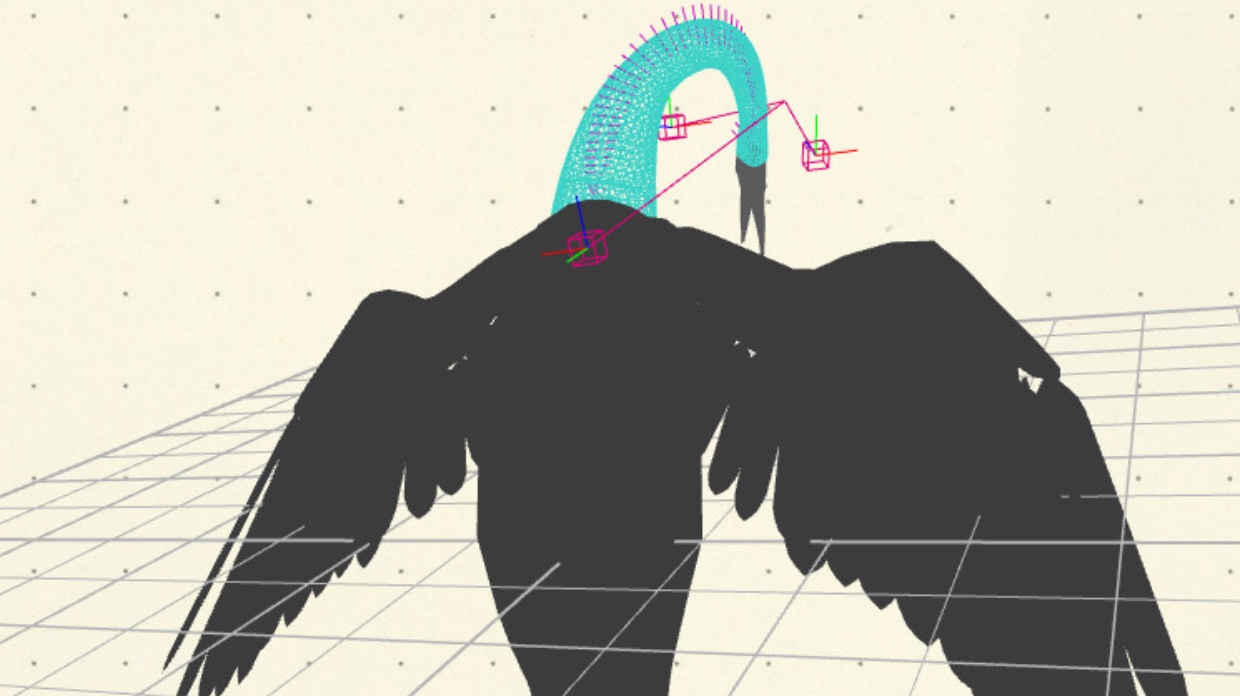

But perhaps the biggest difference was the exciting extent to which the panel discussions nabbed my attention this year. (Though it would have been cool to have VR presentations presented in VR, alas, we’re still in the old-school age). Sure, works like Ram Devineni’s much-heralded Priya’s Mirror — a one-of-a-kind, 21st century (social issue) comic book that added the FilmGate Special Jury Award to its long list of accolades — lived up to its hype and then some. (Green readers take note – Devineni confessed to me that he not only subscribes to the print edition of Filmmaker, but “recycles” the magazine by using the pages as shipping padding for the augmented reality artwork.) And Nick Hardeman’s Snakebird felt less like a work-in-progress than a really fun way to kick back and relax by tossing fish to an oddball bird, pushing a creeping fog away, and interacting with a snake and alligator that appear at random in a virtual Everglades. (That said, the educational component has yet to be realized. I didn’t learn a thing about the anhinga — other than it likes seafood and finds reptiles annoying.) But these were projects that I assumed I’d find engaging. Panels are always an iffy prospect, highly dependent on how well the media-maker is able to translate the creative process into layman’s language.

Several panels stood out as being particularly effective. Though “PM Haptics: Sensory Storytelling” wasn’t on my must-catch list (I’ve never even used the word haptics before this paragraph) I luckily wandered into the early afternoon session. Having briefly met the deceptively humble presenter Dave Birnbaum (design director at Immersion Corporation, whose bio includes being “named as an inventor on over 70 patents in the fields of user experience, wearables, gaming, medical devices, mobile communication, and rich interactive media”) at the opening party the night before, I was curious to learn more about the world of sensory immersion.

Right from the start, Birnbaum’s emphasis on all the senses, most certainly including touch, struck a chord. Or as Birnbaum put it, “Otherwise it’s just VR for the eyes.” (When it should be virtual “reality.”) Indeed, I’ve long thought that we’re beyond the point of filmmaking’s “show don’t tell” mantra. Future media will require an “immerse don’t show” mindset.

What’s more, the speaker’s focus on tactile importance, on haptics technology itself (which even works in 360), on “hedonics” (sensations that feel good or bad), was easily digestible. Intriguing questions such as, “Exactly how much vibration is necessary to make your story come through on mobile?” were brought up. Haptics works best as an enhancement rather than as an add-on or afterthought, Birnbaum offered at one point. He also noted that, “vibration is seasoning.” (And at this point I have to confess, as a CineKink alum with a keen interest in how VR — and especially tactile technology — is primed to transform porn, visions of 21st century peep shows were dancing in my head by the end of this insightful lecture.)

On the second (and last) day of FilmGate, “The VR Generation” panel put an international perspective on the new medium. The discussion featured the creative forces behind Giant, which debuted in the New Frontier section of last year’s Sundance Film Festival (and which, incidentally, makes terrific use of haptics) and Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness. (Both projects also played the festival, with Notes ultimately, and unsurprisingly, taking Best of Fest that evening.) Milica Zec, who’s spent close to a decade working with Marina Abramovic (including on MoMA’s “The Artist is Present” show), explained that Giant, based on her own experiences as a child growing up under the bombing campaign in Serbia, was originally intended as a short film. But as Winslow Porter, her co-director and a new media vet (Giant marks his fifth VR project) added, it needed to be a VR piece — the medium providing the only way to put the viewer inside of the harrowing experience.

When the moderator inquired about audience response, Arnaud Colinart, a French producer (whose brain I’d already picked in this piece) noted that people cried during last year’s Sundance premiere. Even more powerful for him, though, was the response from their subject John Hull’s wife, who told the creators that John experienced rain just as they’d presented it. Colinart’s fellow Parisian Fred Volhuer, who handles marketing and distribution for the VR project, theorized that “left brain” people like the “learning about” aspect of this new universe, while it’s the “right brain” folks who are moved to tears. (I guess that makes me a left-right brain person.)

The moderator then asked about revenue models for VR. The panel seemed to agree that it’s not much of a user market yet. (And also that we’re way behind China — surprise, surprise — when it comes to the number of VR companies.) Porter brought up the differences in the various gear; Samsung VR, which Notes utilizes, has a computer built in, whereas Oculus Rift (and others), which Giant uses, are tethered. “We’re still at the phase where people are more focused on the technology than on the content,” Colinart concluded. “We’re just starting to care about content.”

And concluding the event (prior to the requisite Super Bowl party, of course) was a big screen showing of Peter Middleton and James Spinney’s award-winning documentary Notes on Blindness, which made for a lovely “companion piece” to the VR star of the fest. Though to call either project a companion to the other is more than misleading, as these are two separate artworks in their own right. It was a smart, 20th=century way to close out another successful FilmGate and to usher in a medium that will one day be considered cinema’s equal.