Back to selection

Back to selection

Power to the Priya: Ram Devineni on his Augmented Reality Comic Book Series

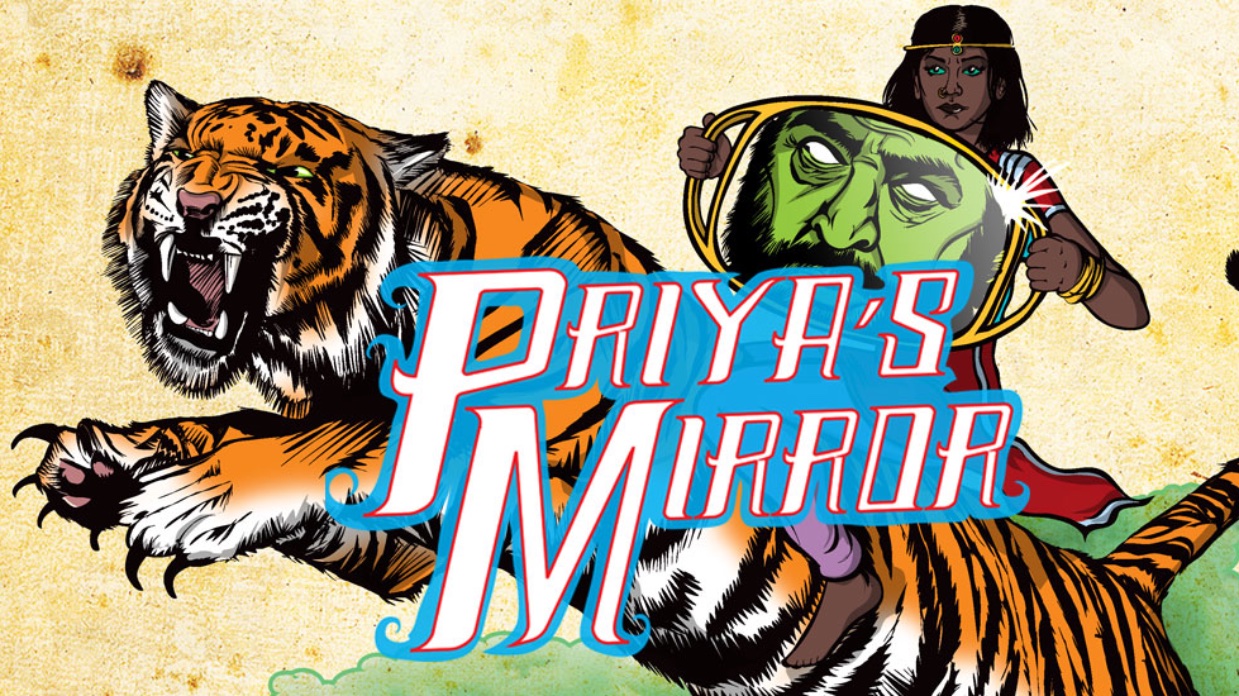

I first met Ram Devineni, creator of India’s first augmented reality comic book, Priya’s Shakti, at the FilmGate Interactive Media Festival in February, where he was presenting the graphic novel’s follow-up, Priya’s Mirror. (This work ended up taking the FilmGate Special Jury Award). With the series Devineni and his co-creators have revolutionized the comic book form, and not just technologically but also culturally. A survivor of gang rape in the first installment, Priya joins forces with acid attack survivors in the second, rendering the titular super-heroine tougher than your average Western badass chick.

Devineni is participating in the Art, Technology & Change discussion at this year’s CPH:DOX, and Filmmaker was able to catch up with the AR artist prior to the fest for a brief chat that ran the gamut from comic cons, to the Sistine Chapel, to creating sociopolitical art for a global audience.

Filmmaker: Can you talk a bit about what inspired Priya’s Shakti? This seems quite a heavy subject to tackle in comic book form.

Devineni: I was in Delhi when the horrible gang rape happened on the bus in 2012, and I was involved in the protests that soon followed. Like many people, I was horrified by what had happened and angered by the indifference exhibited by government authorities at every level. There was an enormous outcry, in particular from young adults and teenagers — both women and men. At one of the protests, my colleague and I spoke to a Delhi police officer and asked him for his opinion on what had happened on the bus. Basically, the officer’s response was that “no good girl walks home at night” — implying that she probably deserved it, or at least provoked the attack. I knew then that the problem of sexual violence in India was not a legal issue; rather it was a cultural problem. A cultural shift had to happen, especially views towards the role of women in modern society. Deep-rooted patriarchal views needed to be challenged.

What I noticed after talking with both rape survivors and acid-attack survivors in India is that society’s reaction and stigmatization of them intensified the problem and their recovery. How they were treated by their family, neighbors and society determined what they did next. Often they were treated like the villains, and the blame was put on them. Our comic book focuses on this and tries to change people’s perceptions of these heroic women.

I think the power of our comic book series is that we are presenting very difficult topics — gang rape and acid attacks — in a very approachable and empathetic way. Readers can relate to the characters and story, and especially the main character Priya, and understand these problems without being turned off by them. Creating a female superhero and using the genre of “superheroes” provides readers with a familiarity and accessibility to the comic book and these problems. The goal of the comic book series and our partnership with the World Bank’s WeVolve program is to reach teenagers.

Filmmaker: Why utilize AR to realize the work? What does augmented reality allow for that traditional graphic novels (or even film for that matter) don’t?

Devineni: From the beginning I wanted the comic book to have an interactive component that is accessible and to reach wide audiences in India and around the world. It was only when I traveled to Italy and spent time in the Sistine Chapel did the idea of augmented reality fully come to me. I was captivated by the splendor of Michelangelo’s achievement. Each fresco panel told a distinct story, and together illuminated a greater and divine experience. I wanted to go deeper into each painting, but was limited by the periphery of my senses. That’s when the idea of using augmented reality technology came to me as a way to experience the real world without being removed from it. Augmented reality compels you to interact with your surroundings and gives you additional information and a new perspective on what you see around you.

What is amazing about augmented reality and comic books is that it allows us to embed many story layers into the artwork, and allow readers to go beyond the story. The images are markers that are activated through the Blippar app (our AR partner). The image can be mounted on a wall, printed in a comic book, seen on your computer screen, or even on a large mural on the side of a building — and the AR will still work. The AR is really effective when you see it on a printed comic book or on street art; they are the perfect format for AR.

On a technological level, we believe the use of augmented reality has a significant impact on readers in India who are not as familiar with this approach. There is a huge “wow” factor when readers first experience augmented reality. Whenever we show the AR at festivals or at the comic cons audiences are impressed. When they see what is being presented they are then moved and inspired.

Filmmaker: How did the U.S. government-sponsored tour of India come about? And how did audiences there receive it?

Devineni: The U.S. Consulate in Chennai had an open call for organizations and individuals to do workshops and lectures on using comic books and cartoons to address social issues. We applied and they loved our application. We held events in two cities officially through the consulate, but ended up doing lectures in many others.

All of the events were a big hit, and also surprising because there is no comic anywhere close to Priya’s Shakti in India. The use of art, technology and social activism is very unique in India — and revolutionary.

Filmmaker: One of the themes of the Art, Technology & Change panel you’ll be on at CPH:DOX is art’s potential as an activism tool. I know you’ve been distributing physical copies of Priya’s Shakti to rural schools across India in an effort to increase awareness of rape and to encourage women and girls to speak out. However, I’m also wondering if there’s any effort to reach what seems to me to be an equally important audience: the adult men (many of whom frequent events like Comicon, I presume), whose patriarchal ideology is at the root of the problem of gender-based violence.

Devineni: I just need to clarify that we actually have not been able to reach rural areas or schools in rural areas, mostly because this is an issue of scale. We have printed 20,000 copies and have been distributing them at comic cons in India and soon in schools in Delhi through the Lions Club of India. And we’ve had over 500,000 digital downloads and over 500 new stories reaching 26 million people worldwide. (And millions more through the murals and social media.)

For many organizations this is a lot and effective, but I also understand the limitations of our efforts. India has over a billion people and to even reach a small percentage of that requires an infrastructure, partners and scale that I do not have. Even the best NGOs in India (or anywhere) only reach a small drop of the entire population. What I am hoping will happen is that the school distribution and testing through the Lions Club of India will lead to a large distribution plan. I think the most cost-effective way to reach teenage boys is through the schools.

To answer the question of adult men, I have not been tracking this, and most of the people who pick up the comics at the comic cons are teenagers, and also parents picking them up for their children. Again, this is an issue of scale. We have no problem distributing or reaching men, but our main focus has been on teenagers because they are at a critical age at which they are understanding gender roles, sexuality and relationships. So I think the comic book can be an effective tool for them.

Filmmaker: So what’s next for Priya’s Shakti? Will the series continue? Are there plans to take the outreach global?

Devineni: The first chapter, Priya’s Shakti, was very particular to India, but to our surprise it became a global hit. Even though we designed the first chapter with Hindu images and a storyline that every Indian will understand there was something about the main character Priya that resonated all over the world.

For the second chapter, Priya’s Mirror, about acid attacks, we expanded the focus and included acid attack survivors from other countries, but still it was very Indian. I think the next chapter about sex trafficking called Priya and the Lost Girls will still be set in India but will not utilize the Indian mythological elements. The story will be closer to Tolkien and fantasy. And we are doing this in order to reach a global audience since the problem of sex trafficking is very similar on a global level. We hope to partner with NGOs all over the world to spread the comic book and utilize the VR. One of our big NGO partners is Apne Aap, which is based in Kolkata and works to educate and provide alternative paths for exploited women and their children.

(Digital comic artist) Dan Goldman and I were in Kolkata in October and interviewed exploited women in the red-light areas. We plan to recreate the Sonagachi, the largest red-light district in Asia, through a mixture of AR and VR. This is in the early stages of development. The major issue of filming in Sonagachi and interviewing exploited women working there is that they do not want to be filmed — even though they want their stories to be told. So creating a virtual city might be a good alternative. We feel it is critical that audiences understand the location and situation they inhabit. Sonagachi is a very surreal place — a city within a city.

Many of the women we interviewed were unknowingly lured into the brothels of Sonagachi. All of them were destitute and came from rural areas and lacked any education. A lot were from Nepal and other bordering countries. Some of them were in abusive relationships or violent situations. The women often trusted a distant relative or remote friend who told them that there was good work in Kolkata. Once they arrived in Sonagachi, they were immediately sold to a brothel or pimp who forced them into prostitution.

We will create a highly engaging virtual reality experience set in Sonagachi and featuring the voices of the women living there. The power of virtual reality is that it makes you feel like you are physically in the story, and immerses you into the surroundings. The VR experience and Google Cardboard headsets will be free to NGOs in Nepal and India so they can show families and educate women about the brothels so they will not be falsely lured into them. Virtual reality is a powerful and affordable educational tool alongside the comic book.