Back to selection

Back to selection

“You Get To Be In Places You Have No Business Being”: Political Filmmakers Talk About Telling Big Stories With A Small Focus At IFP Week 2019

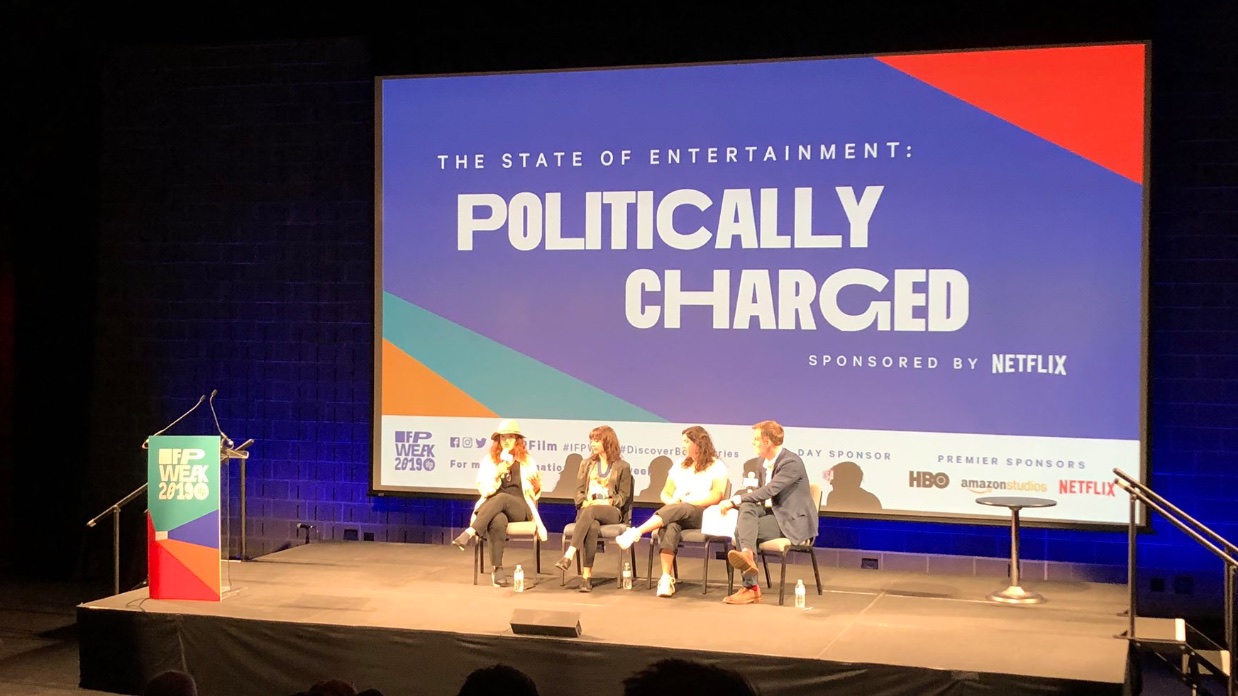

(l to r: Jehane Noujaim, Rachel Lears, Alison Clayman, Christopher Booker)

(l to r: Jehane Noujaim, Rachel Lears, Alison Clayman, Christopher Booker) For documentarians, especially ones who focus on politics, it’s not enough to have a strong and vital subject. You need a way to get audiences engaged. The participants at the “Politically Engaged” panel at IFP Week 2019 know that all too well. Take Jehane Noujaim. Along with her creative partner Karim Amer, she makes docs about hot topics: the Egyptian Crisis in 2013’s The Square, the Cambridge Analytica Scandal in this year’s The Great Hack. But they’re not expository info dumps. They’re verité, following people, not merely ideas.

Noujaim realized that earlier on. She got her start working with the legendary non-fiction team of Chris Hegedus and the late D.A. Pennebaker. One of her first films with them was Startup.com, released in 2001 and following one of many digital companies that suffered a quick death in the dot-com bubble during the early days of the online revolution. It was a break-out documentary that year, but not only because of its timely subject.

“Audiences were fascinated with what happened to these characters,” she said. They cared, she believes, “because we told the story in a very personal, very human way.”

When it came time to make her solo feature debut, 2004’s Control Room, Noujaim did the same thing. She decided to tackle the media coverage of the newly-launched Iraq War by zeroing in on the employees of Al Jazeera, based in Qatar. “I thought if I could get people to really stand in the shoes of people whose perspective we don’t usually see,” Noujaim said, “that would be the best way to deal with these political subjects I thought were so little understood.”

There’s another perk to foregrounding people, not subjects: Those people can help lead you where you need to go. For The Great Hack, Noujaim and Amer structured the film around people involved or affected by the Cambridge Analytica scandal. “We needed powerful characters to take us into these rooms you don’t otherwise see,” she said. “That’s the fun thing about verité: I go into these films with so many questions, and you don’t know the answers and I don’t know where it’s going to lead us. You’re so ignorant about the topic that you don’t even know what questions you’re supposed to ask. Often times you’ll just film what’s happening in a room.”

The panel’s other filmmakers are also advocates of telling big stories with a small focus. Alison Klayman made her directorial debut with 2012’s Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, which traced the activist artist’s belligerent relationship with China’s restrictive authorities. That film depicted its subject as a hero; her latest does not. The Brink trails Steve Bannon, the notorious Breitbart honcho-turned-Trump administration architect. Bannon’s infamy was such that he was the star of another recent doc: Errol Morris’ American Dharma, done in Morris’ signature epic sit-down style. But with The Brink, Klayman — who was hired to make the film, and had no interest in Bannon prior to the gig — treated him to the vertié approach. But she knew even when being a mere fly on the wall, she still had to tread carefully.

“I was making a film about someone I wasn’t trying to endear audiences to. To me, the worst outcome would be if it furthered his cause in any way,” Klayman said. She ensured he had no input in her edit; her pitch to him was that she would be “fair.” Still, Klayman sensed Bannon might not have understood that he wouldn’t come off all that well. “My feeling is he didn’t really know the power of verité.” For her, a fly-on-the-wall approach was the only way to deal with someone who’s a manipulator and a propagandist. “I believed it was not his film; it was my film. There was a way to have him be the center of a film but it not be a commercial for him, and yet still be journalistically fair.”

How did a filmmaker who’s worked with Ai Weiwei manage to not enrage one of the far right’s most paranoid noisemakers? “My goal around him was to be a pleasant person with no needs,” Klayman revealed. “I tried to never seem hungry, or that I needed to go to the bathroom. I didn’t need help with anything. All I wanted him to think about me was that I wanted to film and turn the microphone on.”

As a result, Klayman enjoyed one of the perks of being an adventurous documentarian: Bearing witness some crazy stuff. “You get to be in places you have no business being,” Klayman said. “In this case, I felt an extreme sense of mission. It was not enjoyable for me to be in those rooms, but if I was filming I was happy because I was capturing it to craft something I can share with everybody else.” And she knew it can’t hurt to ask. “I was always amazed at what people let me film.”

Sometimes getting people to let you film them, to sign the correct forms, can be tricky. With Knock Down the House, Rachel Lears had incredible luck: She had a camera trained on Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez before she’d even decided on her congressional run, and thus got to document her rise from working class prole to scourge of the right-wing. One person who wouldn’t participate: Joe Crowley, the longtime representative Ocasio-Cortez would defeat.

“None of the incumbents wanted to participate in Knock Down the House,” said Lears. But as filming wore on, it was clear she needed Crowley, to some capacity. Luckily the debates were open to the press; during some of those, Lears was the only person with a camera running. On top of public appearances, she could rely on news footage. “We wanted to make sure that his voice was in the film. When we edited those debates, we really tried to make sure he got across some of the main points he was trying to get across. We had no interest in making a hit piece.”

All three filmmakers are making timely films during a chaotic period in American history. But these films will live on. After all, they’re documents of a time that will be studied, scrutinized, in a hopefully much calmer future. What will people of 20 years from now think about, say, a documentary that follows Steve Bannon? But that they filmed him at all will surely be appreciated by ensuing generations.

“The thing I always think about is, what if we had a camera on the inside of the Nazi headquarters when they had dinners,” Klayman postulated. “What would their conversations be like? Would you actually find Goebbels kind of funny sometimes?” She believes such a film would destroy the notion that they were merely bad apples but rather real people who were able to get away with the unspeakable. “You can’t pretend they’re monsters or aliens or robots; it’s actually safer to think of these bad actors like that.”

Noujaim hopes — and she admits it’s a big hope — that The Great Hack will stand as one of the things that inspired the populace to start thinking about their relationship with data-collecting companies. She also imagines future audiences will look at her films the way she looks at older documentaries, like 1993’s The War Room, the classic Clinton campaign doc by her old colleagues Pennebaker and Hegedus. “When I watch them, they’re like time machines,” Noujaim said. “They take me back to a time I’ll never get to experience.”