Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Consider Myself a Sensitive Person”: Editor Carolina Siraqyan on The Eternal Memory

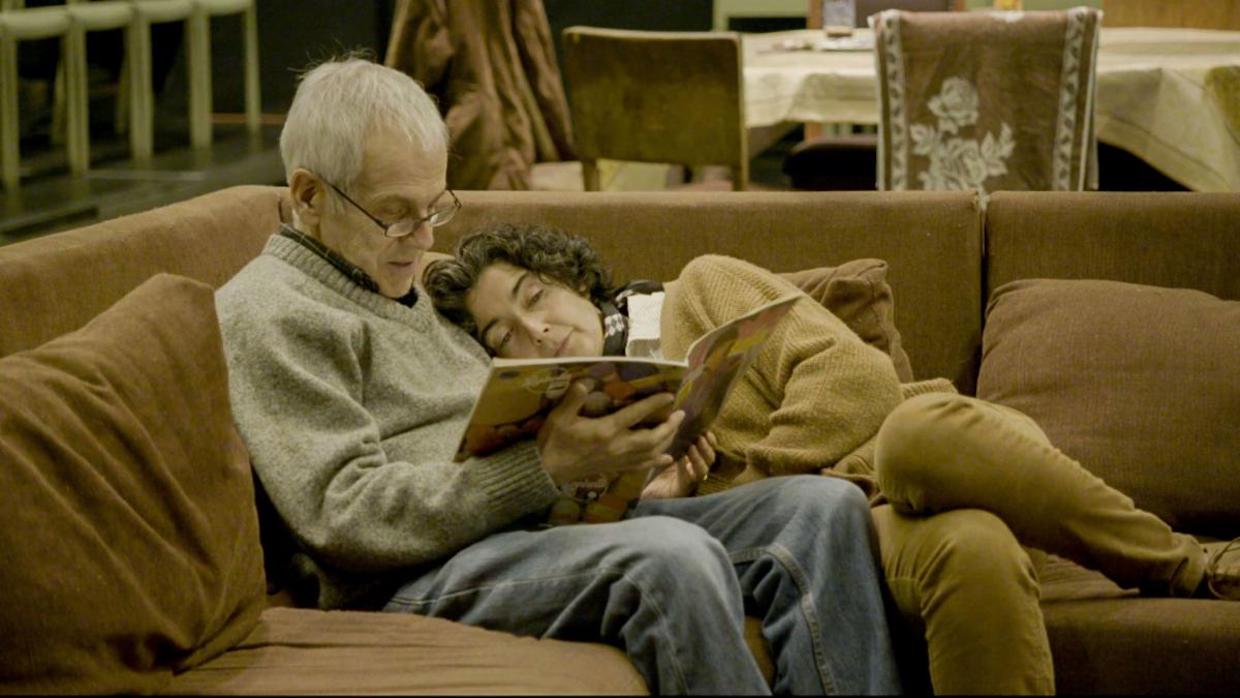

The Eternal Memory, courtesy of Sundance Institute.

The Eternal Memory, courtesy of Sundance Institute. The Eternal Memory, the latest from Chilean documentary filmmaker Maite Alberdi, follows a couple on a difficult journey after husband Augusto is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. They have been married for 25 years, and August has lived with the disease for eight years at this point. As his memory fades, wife Paulina takes care of him and ensures that above all, Augusto is cognizant of how much he is loved—even if he eventually forgets the woman who provides it for him.

Editor Carolina Siraqyan talks about cutting the film and the process of working with Alberdi.

See all responses to our annual Sundance editor interviews here.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Siraqyan: I have been working with [director] Maite [Alberdi] for years. We complement each other very well. We engage in a very stimulating working dynamic. It’s been years since the filming of this documentary started until its completion, and we both enjoyed the process in all its stages. I consider myself a sensitive person, with a lot of patience when faced with a lot of material and a great willingness to open up to changes.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Siraqyan: As an editor, my goal in advancing the film from its earliest assembly to the final cut was to balance the story’s emotional factors and to enhance and preserve the elements of the film that showed the love and care that the characters had for each other, despite the challenges they go through. Alzheimer’s is a harsh disease, and the situations were often difficult to watch. It was essential to find a balance between the dramatic scenes and the scenes of love, so that the viewer could watch the film without losing the emotional impact of a love story.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Siraqyan: One important aspect to achieve these goals was the emotional classification of the material, which allowed us to create a structure and generate the film’s desired arc.

The use of music, especially in the quieter moments, with covers of well-known romantic songs, helped us to tone down the denser emotions when necessary.

Once we felt confident with Maite in the film, we started showing it to specific film professionals inside and outside of Chile. This feedback helped us fine tune it and make the necessary adjustments, to ensure it was as emotional and universal as possible.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Siraqyan: I got into the business by studying audiovisual communication. I started working as an assistant editor and learned by working, since this specialty wasn’t offered in my undergraduate studies. During the 1990s, Chile’s industry was mainly focused on advertisements, trailers, and music videos, so I had a lot of experience working on those types of projects.

I was an assistant for three years for Carlos Marquez, an editor of much experience and sensitivity. He was always very willing to teach me. Thanks to him, I obtained the foundation I still use in my editing style. In recent years, I am dedicated almost exclusively to cinema, where working with Maite Alberdi has been very influential. She has a way of facing projects and a point of view that has been very inspiring for me.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Siraqyan: I used Premiere Pro as my editing system. I prefer this program when editing documentaries because of its compatibility with a whole spectrum of formats. I also like its editing interface, especially the timeline, which is very versatile.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Siraqyan: The most challenging aspect during editing was working with the archival footage. Throughout the process, a lot of archival footage surfaced, even near the end of the editing process. This often meant changing the film’s overall structure. Among the scenes with archival footage, the first one was the most difficult. It was necessary to decide what to say about each of the characters. Both of them are public figures with a lot of recorded history. Here I did many editing tests, and showing cuts to people unfamiliar with the characters and their backstory, mainly foreigners, helped us a lot.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Siraqyan: Maite always wanted this film to be about love, about how a couple who love each other face such an adversity as Alzheimer’s. From the beginning of the filming, Maite’s footage reflected that love. When the pandemic started, Paulina had to film during the confinement. We had access to an intimacy that further demonstrated this love. In the end I was very moved to see how the love between them still went on and that the memory of love is the last thing to be lost.

What surprised me, not seeing this irony in the beginning of the montage, was how the lifelong work of Augusto Góngora contrasts with his illness. As a journalist, he focused his work on maintaining the historical memory of Chile, recording it in many ways, visually, writing… The parallels between Chile’s historical memory through his archival footage and Gongora’s memory diluting because of his illness was very strong. Now that the process is finished, I feel that the documentary’s impact on people is greater than I imagined. It makes them analyze priorities and reflect deeply on love, caring and being cared for.