Back to selection

Back to selection

Getting Friends and Strangers to Watch Your Short Film: Frank Mosley and Hugo De Sousa on Good Condition and The Event

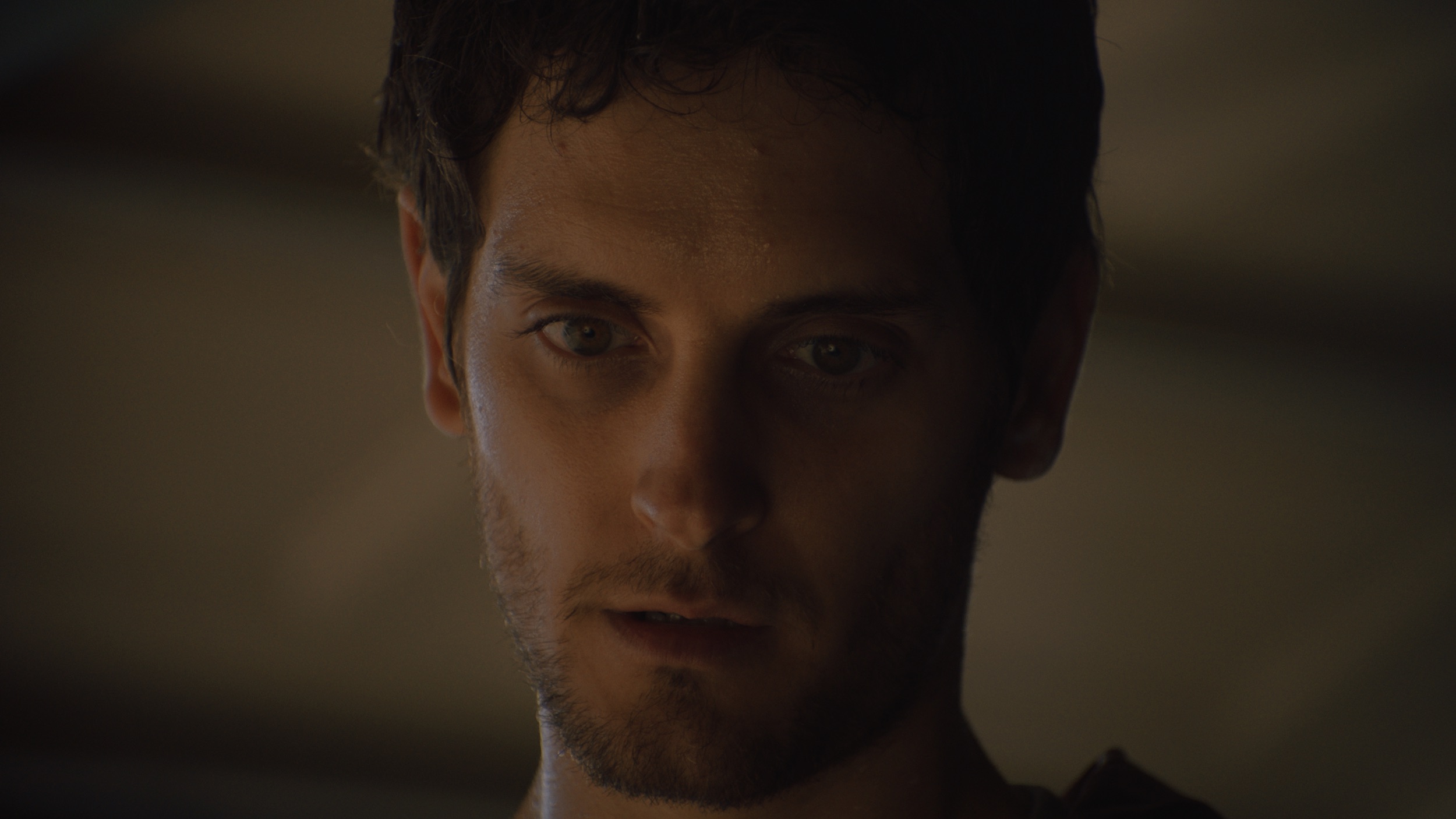

Hugo De Sousa in Good Condition

Hugo De Sousa in Good Condition Good Condition is an eight-minute meditation on loneliness, technology and new beginnings. It marks the second collaboration between filmmakers Frank Mosley and Hugo De Sousa after their 2022 comedy short film, The Event, in which a filmmaker wakes up his roommate in the middle of the night to ask why he hasn’t watched his short film. This time, they embark on an eerie trip to the suburbs, following a melancholy man named Barry (Hugo De Sousa) trying to complete a transaction with a ghostly figure who keeps evading him. Good Condition premiered at Aspen ShortFest and Fantasia earlier this year, and will finish its run this November at the Cucalorus Film Festival.

For the online release of Good Condition, Mosley and De Sousa sat down with filmmaker Patrick Brice (Creep, The Overnight) to discuss their two collaborations. Click here to watch Good Condition.

Brice: I love these movies on multiple levels. With The Event, you guys tapped into something universal when it comes to the community of filmmakers I know, this idea of making something and putting it out in the world, and the fear and anxiety that comes with [that]. Will someone like the thing that I made? Will someone even have the time in 2023 to watch the thing I made? Let’s start with where that idea came from and what your personal experience is.

De Sousa: We know it’s impossible to convince strangers to watch our stuff, but it’s equally impossible to convince people that love us to watch our stuff. They want to watch it, but for some reason, they don’t get to it. I just felt that was funny.

Brice: Was that something that ever hurt your feelings?

De Sousa: I mean, yeah. I’m the youngest in my family, so it’s hard to get people to pay attention to you—I still have that in me a little bit. I’ve been in both places; I empathize with both characters, and that was really important to us. This couldn’t be just me getting back at people for not watching my stuff. I do the same thing too. So, I’m calling myself out.

Mosley: We want to provide a whole triangle of perspectives—not just warring between these two sides, but then you have Jen Kim, who is almost like an audience surrogate watching this unfold. You always have the person on the outside of these situations who’s like, “Look, I don’t really want to be pulled into this.”

Brice: I found myself in that position many times. Once you make stuff that’s being seen in the world, you have people wanting to send you work. I mean, you guys literally did it to me. I’d be curious to go back into my emails and see the time between when you sent me the link and when I watched it. I bet you it was at least a month. Sometimes it’s harder to watch a short film than watch a feature. I don’t know why that is. When I talk to film students and they ask for advice about making stuff, I’m always like, “Just don’t make anything over 10 minutes.” No one has the attention span to watch anything longer than that for some reason. You might as well be just making a feature. Same with how much money and time and effort goes into making a movie, and that’s the other thing you guys did really well. You were so economical and smart and deliberate with your choices. You fully understood your constraints going into it. Can you talk about how that was built from the script stage and considering what it would look like as a production? How long did it take to shoot, by the way?

Mosley: One long night—12 shots, 12 minutes. Everybody involved knew what we were going for, in terms of, we’ve got to get everything this one night.

From my perspective, this started as a great opportunity to have a two-hander with Hugo as actors. There were a lot of ideas floating around, but ultimately we settled on making something at Hugo’s house, which we knew we had control over, with a small cast and crew. If we know we’re only going to have 12 shots, then we use that time to make sure each shot is exactly what we want rather than scrambling to shoot twice as much in one day.

Brice: And you’re getting a new piece of information with each shot. There’s no double beats in it, which is refreshing. Hugo, I’m going to say you’re the antagonist.

Mosley: I always love it when I hear who says which character is the antagonist. You talk to a different person, and the answer is always different.

Brice: It’s fun to watch Hugo needle Frank, but it’s also really fun to watch Frank get needled. And from an acting standpoint, I could tell you guys listen to each other. Did you guys have experience acting together before this?

De Sousa: People are very surprised when they hear this, but we met in person for the first time during the location scout in my house. We’d been talking on the phone or Zooms and decided to co-direct before even meeting each other in person. It’s something that could have only happened in 2020. But people are surprised; they think we’re like old friends when they watch it.

Brice: By the way, they’re both Valley movies. I’m sure you guys are aware of that too.

Mosley: That makes us so happy, because we kept thinking about early PT Anderson. Looking at those trees down the alley at the beginning of Good Condition, this could be Punch-Drunk Love.

Brice: Yeah, early morning in the San Fernando Valley, there’s something very specific about that. It’s desert adjacent, so it gets cool at night, but then it warms up really quickly. So, you get mist in the air and that nice, soft golden light.

Going on to Good Condition, was it you guys taking that same model and saying, “How can we make something in a day?”

Mosley: We had a lot of fun with The Event and it was like, what could we do as a follow up that could be another collaboration, but in a way that was very different than what people might expect coming off of The Event? Not just in terms of the story, but the tone and aesthetics—it’s not just locked-off camera work for the most part. But again: using our resources, how can we do all that at Hugo’s house again in one day with a really small crew?

De Sousa: Every short is an exercise in simplicity, because it’s hard to justify spending a lot of money on a short film, so we have to be inventive.

Brice: I’ve thought a lot about this experience of purchasing something on Craigslist, what can happen when you’re putting yourself in that position and the risk that you’re taking. Even when it’s a table, you’re still saying, “This is worth putting myself in danger.” Have you guys had any Craigslist experiences that inspired this?

De Sousa: Not really. I mean, I have the most pretentious answer for how I came up with the concept. I was reading a Kiarostami book, and in it, he tells his students to make a short film set in an elevator. Everyone makes a short film set in an elevator. I’m like, “OK, I don’t have access to an elevator, but what else in my house is cinematic? My garage is the only remotely cinematic thing.” And as soon as I pictured my garage, I immediately saw a coffee table in the middle of it. That was my starting point.

Mosley: We were talking a lot about paranoia in the piece and how to really bring that to the surface. Is he being watched by someone? Perhaps his gaze at the table is being mirrored by someone else’s gaze. One of the things we watched right before shooting was Samuel Beckett’s sole movie, Film, with Buster Keaton. There’s this comic energy to it, yet there’s a desperation for this person who’s running the whole time. It’s a chase movie, and you don’t know what he’s running from. Then you realize at the end, “Wow, the thing he’s running from is us, is the gaze of the camera.” We wanted to have that kind of feeling. We’re always trying to lock into Hugo with the camera as he’s going through these actions of trying to do something as simple as getting a table. Each time those zooms start, it’s almost like the trance begins. By the last zoom shot, we’re as close as we are allowed, because he lets us in on the porch during that monologue. You know, vulnerability.

Brice Back to the minimalism of it all, like no music. Music would only get in the way. You guys are wanting us to focus on one or two things, and that’s it. So, how do we make those one or two things interesting and propulsive and fun to watch? Were you guys fully aware of this minimalism? Was that something that you were like, this is what we’re doing? Or was that something you stumbled into with The Event and then decided to take further with Good Condition?

De Sousa: I think we have the same taste when it comes to that. We were interested in how much we can do with nothing. We’ve been pushing that further with every short. The first one is a super-contained story—two people stuck in an apartment—and then the second one is an actor and a coffee table.

When we were sending out the short for notes, it was hard to navigate, because everyone is so different. Some people want answers and some are cool with not getting all the answers. It was really tough to navigate that process and not feel like there was something wrong with the short. It was our intention to do something super-ambiguous. I really like Cruising, and the ambiguity in that film is so beautiful—that was the goal going in. But it’s tough when you see that some section of the audience is like, “I don’t know what’s happening.”

Mosley: You have something very grounded and literal as the conflict at the heart of The Event, but with Good Condition, so much is ephemeral. The themes are floating around one person, an unreliable narrator who has no bounce board other than the audience. Is it true what he’s saying? Is it exaggerated? Is it not the whole truth? Which we found really exciting. The first half is almost completely silent, then the last half is a big monologue. And that was really exciting for us, to have that bifurcated structure.

We really love economy. Anytime I start making a movie, I try and say, “What am I not going to do with this movie?” I think that’s a great place to start, just making rules and boundaries for yourself because the toy box is unlimited. But if you’re like, “What’s the right toy for this? These are the only two toys I’m going to use,” then it gives me confidence when making the film.

Brice: That idea of showing your work to people was something I think I learned the hard way as being good medicine when it comes to the post stage. It’s tough a lot of the time—not only in terms of the ego death you have to experience with taking criticism, but also knowing you’re showing this thing that isn’t finished and wanting help. Also, weeding out emotional opinions versus practical opinions, weeding out people’s taste versus what you want—it’s really an unclear zone that you’re living in when you’re exposing yourself in that way and opening yourself up and saying, “Help me.” You’re probably going to hear some stuff that you didn’t want to hear, some stuff you didn’t think about.

Also, you’re going to hear an opinion a lot of the time that I think goes back to a line in The Event where you say, “I’m your friend, I’m not your audience,” which is the thesis statement of that movie in my opinion. A lot of times the thing you’re making just simply isn’t for that person. And that’s fine. I’m very lucky, because I had the experience of doing that with my first movie, which was a very different movie than it ended up being, partly because of that experience of showing it to people and getting advice and hearing what was working and what wasn’t. I had the extreme version of that. Now when I show a cut to people of movies I’m making, I feel like I’m a little further down the line of what it could be, and have a better idea of weeding out someone’s knee-jerk emotional opinion versus, like, “Here’s what I can actually take from that feedback and apply to this movie to make it the movie that I want it to be.”

Mosley: The best notes are when someone gives you a note and you’re like, “I don’t really want to do that thing they suggested, but there’s this kernel of truth in that note that I can pull and it can make me look at the film in a different way.”

De Sousa: After getting a lot of notes, Frank and I were a little lost in the sauce for a while. Everything came together really fast: We shot it a month later, we had a cut and we were so giddy about it. Then we went through that process and had to remind ourselves, “Remember when we really loved this thing? We loved it.” So, we went back to that first cut, because we remembered that feeling when we watched it and had to trust that. We toyed with it—we changed the text messages that he receives. But we were stretching the short in every direction trying to please everyone, then we were like, “Let’s just go back to the one that we really loved.” And it’s hard to justify—just, you know, the taste thing.

Mosley: It’s also about intent. We made all these choices in pre-pro to make that first cut of the movie that we loved. There’s something to be said for what Hugo’s saying, that raw first cut and feeling of: “That was our script-to-screen translation, and we did it.” That’s why the editing was so swift because, again, we love economy. The other notes that we got—to your point, Patrick, there were some people whose note was, “Once you put in some music, that is going to be really great in this shot.” They had no idea that we had no plan of putting any music in there, because we don’t want to tell them how to feel. It can be scary and funny and sad all at once without a score. But if you want to make one choice of what type of score, then it becomes this one thing.

De Sousa: And it’s tough with links, because in a movie theater, at least you’re controlling the setting of how they’re watching your movie. But one person was like, “Oh, I watched it during my lunchtime listening to music, and it was too slow.” I also think that’s probably a more accurate representation of how people would actually watch this thing out in the world—sending it to them, knowing that they’re going to be watching on some device that’s got a bunch of tabs open and this is just one of a thousand.

Brice: That’s just the reality of living now. My introduction to cinema was watching VHS tapes, not a movie theater, because I grew up in the middle of the woods. There was a movie theater, I did go see movies there, but in terms of falling in love with movies, it was going to the video store, renting a movie, taking it home: “That’s the movie that we’re watching tonight. We have to watch it tonight because it needs to be returned tomorrow.” Outside of that being a perfect setting to focus on something, it was a different way of experiencing cinema than now, where you can watch it on anything. There is a small part of me, as a filmmaker, that resents the options that we have now. I resent it for myself. My ideal viewing experience for a movie is 10 a.m. with a cup of coffee in an empty movie theater. That is when I know I’m going to be able to focus, to receive, to be moved, to be able to learn. I enjoy watching movies at night, but it’s definitely more of a one-sided experience that way then if I watch it in the morning, when I have time to think about it for the rest of the day. But as a filmmaker, I don’t begrudge anybody that watches my movie in any way. As long as you’re watching it, I don’t give a shit. It’s different when that person’s giving you notes or feedback. But how do you guys feel about people watching your stuff? Do you care?

Mosley: I’m more in your boat. I’m just happy that it’s seen at all. Really, once it’s done, we have no control over anything. We have only as much control as we have making the damn thing. After that, it’s like pushing it off the school: “There you go. Take some steps, see how you’re received.” You have to let go a little bit.

De Sousa: But it’s harder when you’re making something that’s supposed to be a little slower and meditative, and it’s not super choppy and in your face. You get a little insecure when you’re like, “OK, you’re watching on your phone, with some noise around.” They’re not really going to be fully immersed in the tension that we’re trying to create.

Mosley: But when we are having a theater screening, then I want to make sure it’s the best version possible: do a sound check, make sure the DCP is right, all that stuff. There were some screenings of The Event that Hugo and I were at—I think one was the Santa Barbara Film Festival—and we just smiled at each other afterward. Seeing it on the big screen, it looked the best, it sounded the best that it ever had. It was the best version of the movie ever. It was really special.

Brice: The fact that you guys have had the chance to see these in a theater with people, but also know you’re okay with it going out in the world on the internet, which is where they’re going to live now and hopefully have people come and find them, feels like a best case scenario for me, especially when it comes to where and how short films can exist in this world.