Back to selection

Back to selection

“America is Desperate for a Narrative”: Courtney Stephens and Callie Hernandez on Invention

Invention

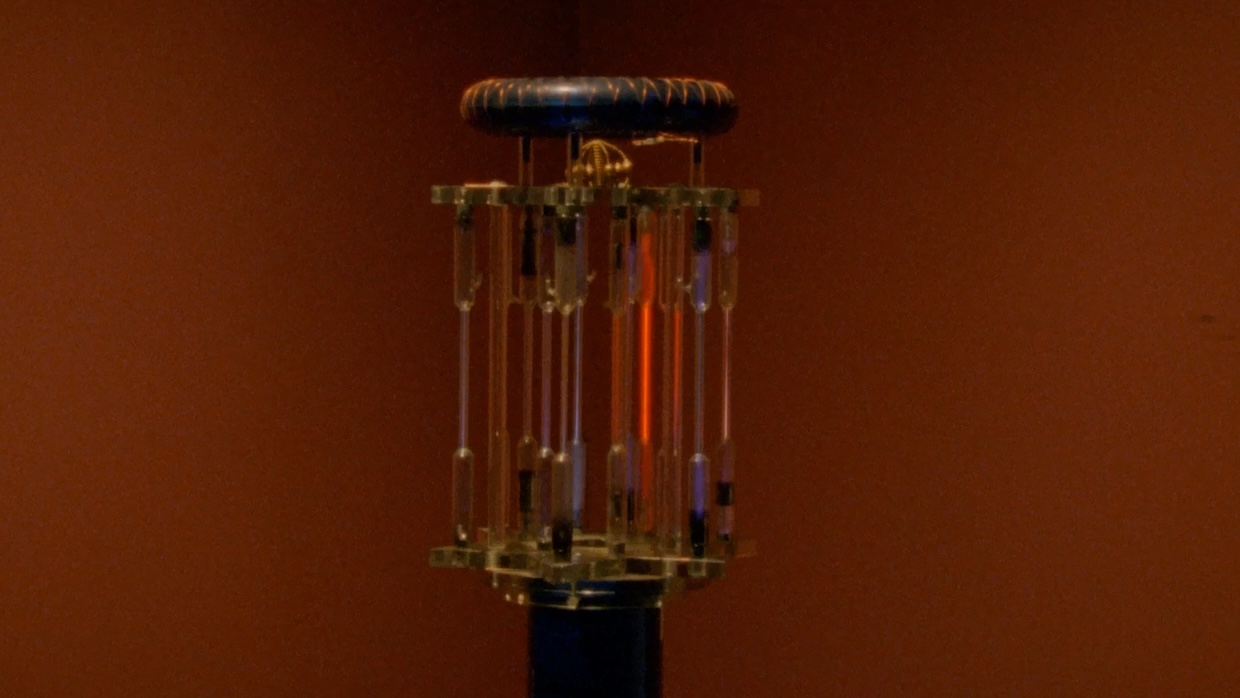

Invention Following a decade of work in experimental and documentary cinema, director Courtney Stephens steps into fiction for the first time with Invention, a remarkably resourceful microbudget drama that nonetheless resists strict categorization. Starring and co-conceived by Callie Hernandez, the film draws upon the actress’s real-life relationship with her late father, a medical doctor turned small-time huckster who made a name for himself on local television talk shows and public access programs in the ’90s and 2000s. In this fictionalized telling set in the Berkshires, VHS footage of those TV appearances weave through a story in which Hernandez, playing a version of herself named Carrie, discovers that her dad has left her a patent for a vibrational healing machine that may indeed be able to ease the pain of her loss.

Despite the narrative framework, this Super 16mm-shot feature furthers Stephens’s longstanding interest in cultural memory, female mythology and the slippery notion of authorship. As the film shifts between archival material and loosely scripted scenes of Carrie’s encounters with a variety of her father’s friends and former associates—including an estate lawyer played by filmmaker James N. Kienitz Wilkins (directors Joe Swanberg and Caveh Zahedi also appear in small roles)—a slipstream of fictions and fantasies emerge from the fabric of multiple intersecting realities, a meta-cinematic conceit Stephens reinforces through use of on-set audio of the cast and crew recorded during production. With Invention, Stephens and Hernandez have fashioned a uniquely reflexive portrait of the grieving process, utilizing personal experience to articulate something universal about death and the ways we mourn the complicated figures in our lives.

I caught up with Stephens and Hernandez a few days before the film’s premiere in Locarno to discuss the collaborative nature of the project and how its multiple registers of reality are never free from fiction.

Filmmaker: Courtney, the first thing that struck me about the film is how different it is from your prior work. Had you always wanted to work in a more fictionalized or dramatic mode, or was it more a byproduct of collaborating with Callie on a film about her life that took you in this direction?

Courtney Stephens: I went to film school at the AFI and thought at the time I would go into narrative filmmaking, but ended up moving towards filmmaking that could be done for no money and focus more on ideas. When we started generating ideas for the project in late 2021, we were actually talking about making a much more straightforward fiction than it became.

Callie Hernandez: Our first film idea was called Dick at the Dump! It was going to be about this guy named Dick who ran the town dump.

Stephens: The title was enough. [laughs] But once we came to the idea for Invention, I understood that we would be using performance as a technique for nonfiction at some level, and that made it more comfortable. But drawing out a performance versus drawing a person out of themselves in, say, a documentary are different things. Callie’s dad also had this interesting archive of TV appearances, which allowed for some play in editing.

Filmmaker: How did you first learn about Callie’s dad and how did the project develop into a collaborative account of his life?

Stephens: Callie and I met 10 years ago through friends, then re-ran into each other in New York at a Hong Sang-soo film screening. A few months later, at a dinner party in LA, we were talking about losing dads, which was still very fresh for Callie. I remember we silo’d ourselves off and talked for hours about loss and our dads. It was almost like that scene in Boogie Nights where Julianne Moore and Heather Graham get into this manic all-night coke conversation.

Hernandez: We weren’t doing coke, though! [laughs]

Stephens: No, but we just started talking about all this stuff you don’t normally talk about when you talk about grief—things particular to the relationship of daughters and fathers. And we sort of said, “We should make a film!” From there, we started talking about the idea of aftermath and this fictional small-town world that could serve as a backdrop to loss. As I learned more about her dad, we began talking about ways to incorporate some of these real elements into it. The probate for her dad’s estate was still going on, so the more I was learning about all this, the more some of the real objects he owned started entering the fiction and taking over.

Hernandez: When we started talking it was very natural. When your dad dies, you tend to talk about it with other people whose dads are dead. It was pretty fresh. I had just wrapped a TV show, and for myriad reasons just felt that I wanted to rent a house in western Massachusetts, which I did for a year. The idea was to make as many microbudget films as I could in this house. And when Courtney and I started talking about our dads, I found the machine that’s in the film in my dad’s storage unit, along with a bunch of other stuff: a polygraph, illegal feathers—all sorts of shit. My dad was really weird. But I got really obsessed with this beautiful, four-foot-tall machine. So I approached Courtney to make the film in the house because I thought it would be cool, and also because I thought we had a similar understanding of having eccentric dads and a sensitivity to that. It just made sense to me: we should make a dead dads movie.

Filmmaker: Callie, what was your impression of your dad’s professional life growing up? Was there a moment when you realized he had, as The Executor says in the film, “a different approach to finances?”

Hernandez: I should say first that I think Courtney and I really didn’t want to make an “I hate daddy” movie. We both really loved our dads. And I still love my dad, and I’m sure Courtney still loves her dad. But growing up with it wasn’t as fun as you would think. My sister actually took to it a lot more. I was definitely the five-year-old being like, “Don’t get near me. I’m not going to get hypnotized. Get away from me.” And my dad would be like, “This is my best friend, Medicine Wolf.” And I would say, “Oh, you’re 206 years old? Yeah, right. Okay, whatever.” I was definitely a skeptic as a child.

Ever since I can remember, it was like UFO detectors and shit. He was a strange bird from the get-go. He was curious about everything, and sometimes you were part of that experiment. There’s a photo—when I got my wisdom teeth taken out, my dad decided to wrap my whole head in these wires. And then there was a laser box where you put your hands in. My dad had so many of these weird machines. He was like, “Put your hands in here.” Then he wrapped my face and I have these huge chipmunk cheeks. I’m looking at the camera like, “I’m gonna fucking kill you.” But it was an experiment to see if it would help the swelling go down. Things like that were part of every day. So I wouldn’t say I loved it or hated it. I was cautious.

Filmmaker: How familiar with the VHS footage were you before making the film?

Hernandez: I remember it really vividly. My dad was a small town hero in a certain way, so it wasn’t news to me. But I was surprised that he had kept everything. I knew that it was documented somewhere, but I didn’t know it was so carefully documented. It wasn’t really my dad’s style to be organized like that, so it was surprising to me that it was all in one box, and that it was all there. But it wasn’t like, “Oh, wow, I had no idea that he had this.” I had never gotten to watch it post-childhood. Being around it as a kid hits different compared to watching it twenty years later.

Filmmaker: How much of this material is there? Was there a lot to go through?

Hernandez: There’s more than what I gave Courtney, because I found more as stuff as the estate was settled. My sister really handled his estate. There were always more things being found. He had lots of different bank accounts and storage units. He had a storage unit in Denver I didn’t even know about. I was like, “Why is there a storage unit in Denver?” He never lived in Denver. Just really strange.

Stephens: We were probably working with five hours of video, maybe four—mostly TV morning shows, but also some public access shows and footage from a public speaking workshop.

Hernandez: And a shit ton of audio.

Stephens: A lot of other archival material that ended up being used in the film in a more abstract way was other stuff from those VHS tapes, advertisements and other segments. A lot of San Antonio specific material, but also just this late ’90s TV zone.

Filmmaker: Courtney, how much of your relationship with your dad is in the film?

Stephens: There’s a fair bit of autobiographical stuff woven into the fictional storyline, which involves Callie’s character trying to salvage this failed business venture, or wondering if she should, and dealing with angry investors. My dad had patented this building technology towards the end of his life, and was trying to build these prototype houses in Phoenix when the 2007 housing crisis hit and everything fell apart. My brother and I made an attempt to save it, but it was impossible and the bank took everything. I remember secretly sitting in on these investor conference calls. It was all super surreal.

Both our dads were these charismatic men in possession of big visions and ideas. I felt instinctually that we were dealing in similar realms of grief, where you also are grieving their fantasy worlds. We process not just the loss of the person, but the loss of their self-mythologizing. My dad always had this sense of his own immortality, throwing down 200 vitamins a day and shooting ginseng, but also reckless in other ways. He was a very intense person who I loved with all my heart. There was a lot in that wake and I had to process it alone, and that was never really going to get resolved. You lose not only the person you love, and who you loved to love, but the mythology they have around themselves, and even fantasies about themselves, which as someone’s child you often enter because you’re very little, and it’s the way to be close to them and to love them. It’s a lot to let go of.

Filmmaker: We started by discussing how different the film is from your prior work, but there’s still a strong documentary element to the film. Can you talk about the film’s relationship with nonfiction?

Stephens: The way the film probably intersects the most with my past work is in terms of media itself. The archive we worked with, these TV shows, are personal for both Callie and for “Carrie,” her fictionalized character, but they’re also in this register of daytime television and national memory. For me, that suggests the way that one’s own family is a kind of media sphere in and of itself, one that generates belief systems but also affect. It’s really one’s first picture of the world, and when we end up in conflict with those belief systems later on it’s often a real struggle to remove the shape of them.

We purposely wanted to leave ambiguous many aspects of the invention that Carrie inherits from her dad and how exactly it works, but one thing this machine does is generate fictions. Following from that, the film has multiple registers of reality, and none of them are free from fiction. There is the TV archive, which is nonfiction but also a space of private memory, a kind of alienating screen upon which to long to connect with someone you’ve lost. It’s very inaccessible. There is the fictional plot of the film, which is shaped from a fusion of largely real experiences Callie and I lived, and there are some hints of the making of the film, which are, of course, also tied to fiction. Then there are these conspiracy theories many of the characters offer Carrie, almost all of which we encountered while working on the production of the film. So, even in those spaces of “invention” we are trying to document America in the present. Actually, America is desperate for a narrative.

Then there is even this element of the other filmmakers who appear in the film, and the sense of their own bodies of work bleeding into the scenes, which adds another later of nonfiction, their real life personae and self-mythology. We were drawing on the bodies of work of those filmmakers in ways we found fun.

Filmmaker: How conscious were Caveh Zahedi, James N. Kienitz Wilkins and Joe Swanberg that you were drawing upon their personas and filmmaking styles in their scenes?

Hernandez: It’s funny, James actually emailed me this morning because I sent him the film, and he was just like, “Oh my god, I’m so buttoned up in this!” He was having a crisis. He was like, “Maybe this is who I really am!” And I was like, “No, you did really well. You played the executor perfectly.” [laughs]

Stephens: It’s crazy, James only mentioned on the day of shooting that his mom is actually an estate lawyer. [laughs]

Hernandez: I didn’t even know that! Let’s see, Joe came in because—I had worked with him a few years ago and we were thinking, who can play this mechanic kind of guy, and Joe was like, “Well, I have a mullet right now, can I keep it?” That’s how he got involved.

Stephens: Just talking about Joe, Caveh, and James: They each are working in these different genres of the real. James’s films are really exploring media and fiction and metafiction. But all of them work with documenting reality and then in some ways framing that as fiction, or within the gaze of fiction. James’s scenes were actually the only scripted scenes in the film, because they needed to be precise with the patent law stuff. With all the other scenes, we were generating and finding the text together. We knew they’d all be comfortable with some level of improvisation, and I even feel like we dipped slightly into their filmic registers. In James’s scenes, we’re not exactly in one of his films, but his amazing delivery, he can’t escape it, you know?

Filmmaker: Yeah, those scenes could pass for one of his shorts.

Hernandez: And Joe, too. When he comes on screen, you’re like, “Am I… in a Joe Swanberg movie?” [laughs]

Stephens: We were working out that scene with Joe the night before, remember? We had all these different ideas—like, “Should there be some kind of seduction? What should it be?” And then Joe was like, “What if I lead her in a prayer?” It was such a great instinct, because it leaves this open tension of whether this person is trustworthy or not. Is he just trying to help heal her? And that was right for the themes of the film.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about the idea to incorporate behind-the-scenes audio into the film?

Stephens: It was truly an experiment. I wasn’t sure we’d ever use the behind-the-scenes audio and rehearsals, but I was pretty interested in that documentation even while we were shooting, because so much actual, emotional stuff was being discussed and coming out. Because we shot on film, I did the audio syncing and ended up listening to all of that again, and just remembering our time on the set and everything that was in the air and being talked about—because of course many people had experience with loss. As we said, it isn’t a strictly fictional, improvised film; it’s an attempt to shape real emotions and experiences into coherent scenes, and some of the production audio helped to reveal that.

Sometimes it was even more emotional than the fiction, which has all these scenes of bureaucracy and other ridiculous elements of estate stuff. With the opportunity to reflect on it you can find humor and pain in it all. Callie, the scene where you play the music for Caveh that you played when your dad was in the hospital is so beautiful. There are these moments in there that I feel are tender because they’re just real.

Filmmaker: In one of the audio clips you actually hear someone say, “We’re making an improvised film.” Can you expand a bit on what you were saying regarding the improvisation and how that worked as far as writing and creating on set?

Stephens: We had an outline, but that outline was shifting as production went along. We had a crew of three people: me, Callie and our heroic DP, Raphael Palacio Illingworth. So we could move pretty nimbly, and things could shift in real time. Things were very flexible but I really wasn’t sure it would all fit together in the end. As for individual scenes, usually we had some lines we’d thought of and a trajectory of the conversation, but for the most part the details were being worked out with the actors on the day of.

Hernandez: I made a film around this same time called Jethica (2022), with my friend Pete [Ohs]. The way we did that film was we shot it in the same house, with a very small crew and half an outline going into it, very similar to this film. We would write scenes the day of—bad, loose versions of what we felt the scene could be, or what we wanted it to be, and then it would sort of evolve on its own. So, I was sensitive to the fact that that way of approaching a quote-unquote improvised film—one with a loose map that we could do a day at a time—might work for this.

Stephens: But we were shooting on film, so it was super stressful.

Hernandez: Right. Jethica was not shot on film, but we did have a more limited amount of time. Shooting film definitely had an effect on what you see, but I’ve found that limitations also make the film become itself, in a way. So I told Courtney, “You know, this worked in the past. I think it might work for this. That’s the structure of how I made the other film in this same house.” I guess I was also sensitive to the fact that the narrative aspect was new for Courtney, but also that she’s very well versed in narrative, even though her films are more experimental. It just seemed to me that it would work.

Stephens: A lot of the improvisation came out of stories that Callie and I had been sharing—or turns of phrase that Callie would use or that someone would say during our research.

Hernandez: And the actors.

Stephens: Yeah, a lot of the actors are drawing on their own lives. There were a lot of blurred lines.

Hernandez: It was extremely collaborative.

Filmmaker: Would you say that this approach helped ease the emotional difficulties that might have presented themselves for you as an actor if you were to have dwelled more on the material ahead of time?

Hernandez: I was doing a lot of different things, whether that was charging batteries or trying to help gaff or running sound or writing or cooking food. I definitely didn’t want to make this film as a display of my actorly talents. I just wanted to make this film with Courtney—together and with everybody that came on board. So I don’t know that anything helped my acting in this film necessarily. [laughs] In terms of the personal nature of it, because there was so much going on, it made it less intense while we were shooting.

Stephens: There was a lot of space to just talk about life. I think you were able to draw from your actual life and that made the scenes make sense in a different way. It wasn’t like, “How does this scene reveal character?”

Hernandez: Yeah, there was an inherent understanding of this world, for sure. For instance, in the first part of the film, I’m quite reserved, almost wooden I would say. That wasn’t something that I was thinking about as an actor. I was thinking about the discomfort that I felt talking to a lot of people who said a lot of similar things after my dad passed away. But it was complicated to find the lines of fiction versus how much I wanted to perform with my dad in mind: what I wanted to reveal, what I didn’t want to reveal. Being busy on a set helps with not overthinking too much. But I would say my real life experience absolutely informed the first portion of the film when my performance is sort of wooden, because it is deeply awkward and uncomfortable after losing someone—you’re not sure what to say and do. Then, as the film progressed I found myself opening up more. When Carrie meets Sham (Sahm McGlynn)—that’s somebody that she feels comfortable opening up to, then she sort of starts to unravel but also open up at the same time. That was definitely my experience as a human. But I wouldn’t say I had any technique in mind. I had no sense of this as an actor. I just knew I was a tool for this film, and that’s what I was interested in.

Filmmaker: Courtney, you’ve acted in the past. Did your experiences as a performer influence your approach to directing actors?

Stephens: I really don’t think of myself as an actor. [laughs] But I have acted a little, yeah. Earlier I said that I feel that I’ve sort of migrated into this space, especially with my last film, Terra Femme (2021), where voice and persona are being used as vehicles for exploring ideas. I had a professor at the AFI who said “Cinema is a great vehicle for emotion, but not a great vehicle for ideas.” I always found that so reductive. We can be moved by all kinds of things in films, and I think ideas can be very emotional. I don’t see a divide there. Here I really was interested in how behavior and encounters can hold ideas about the country and medicine and the last 25 years of technology. So, there was a lot of material in this that was not just about character and performance. At the same time, I was humbled to find the limits of planting information in a narrative film, especially this film, because the film is about an interior wilderness of grief.

Filmmaker: Is there something about the collaborative process in the films you’ve co-directed or made in tandem with another person that you find unique or inspiring in comparison to your solo work?

Stephens: Yeah, this film is completely co-authored. Callie losing her dad was the starting point. I’m kind of a responder as a filmmaker—that’s a mode that I like working in, responding and taking the puzzle of the world as it is, and shaping it into some kind of form that helps to articulate it. Collaborating can always be challenging, but it’s often so much richer. This film ends up being so many aspects of both of our instincts and personalities.

Hernandez: The things you’re saying, Courtney—that you’re a responder: I think that speaks to your background in documentary. That’s your backbone. Ironically, I studied documentary in college. I guess I’m just agreeing that you’re a person who responds, and I think that was necessary, or helpful, for this film.

Stephens: In other films I’ve co-directed, like The American Sector (2020) with Pacho [Velez], we were doing different things on set, so it was almost like splitting the job in two. Here, Callie and I were really looking at it all together but from difference distances.

I remember there was this time period before we started shooting where it was like the film was making itself through a kind of shared set of references and instincts. It was saying yes to what was real and then also trying to embellish that and formulate outlines and structures. Taking scraps of things that don’t all go together and maybe aren’t going to fit in the same film and trying to figure out a way to make them fit, or find a container for things. It’s an editorial sensibility, but it’s something I like doing. I felt like this was an opportunity to be really receptive and hopefully help shape those scraps into something.

Filmmaker: The last thing I wanted to ask you is about the scene in the cornfield with the Alice in Wonderland theme. Do you feel there’s a symbolic connection between Carrie’s and Alice’s stories, or did you just happen upon this location?

Hernandez: We got lucky!

Stephens: Yeah, it was just happening, and we liked it. Because we were thinking so much about fantasy and fairytales and also the structure of conspiracies that get woven by the public—fantasy is so much a part of the news cycle—it seemed great. And in these female-driven fairytales, this idea of all roads lead to home—that was interesting for this film.

Hernandez: I want to shout out [sound designer] Emile [Klein], who put in some really fun easter eggs with the Alice in Wonderland theme throughout the film, which I thought was really special. If you catch them it’s really fun. And I will say that when Court and I first started talking about making a film together we traded books and she gave me one called Basic Black with Pearls [by Helen Weinzweig], and I gave her a book, and we had no idea what these books were about. We just blindly exchanged.

Stephens: Callie gave me Pitch Dark by Renata Adler. And we both read each other’s books and realized that they sort of have the same form, where some kind of un-processable grief has caused this narrator or this fiction to start spiking in directions that start to fall apart or make some new meta-fiction. So we read those and I think understood, “Okay, that can hold the things we want to talk about. It’s about fiction or fantasy as a coping mechanism.” I don’t know if that’s what’s going on in Alice in Wonderland, because she actually just tumbles into a hole, but…

Hernandez: I think it is similar, even if it’s necessarily particular to Alice in Wonderland. But what it is particular to is entering a fantasy world, and being not exactly sure how to distinguish one thing from another. The books that we traded were about two separate women, two separate stories, with un-processable grief and a confusion of what was happening and what wasn’t happening—kind of conspiratorial, which is something that Alice in Wonderland very conveniently lends itself to as well. When we were shooting in the cornfields we just happened upon this area and it just happened to be Alice in Wonderland-themed. So it just made a lot of sense in terms of where the film began—the seeds of the project. It brought everything together.