Back to selection

Back to selection

Andrew Neel and Louisa Krause Talk King Kelly

While there have been many films riffing on reality tropes in the last several years, few have been as cleverly conceived and entertainingly executed as Andrew Neel’s debut fiction film, King Kelly. Set in the world of amateur webcam porn, the film depicts a monstrously fascinating Tracy Flick for our oversexualized social media age. Played ferociously by Louisa Krause, Kelly is a high-school student who runs a profitable one-woman porn empire from her suburban bedroom, with her parents none the wiser. Stripping on cam, uploading details of her everyday life and ruling over her chat room with a gonzo glee, Kelly embodies oversharing capitalist narcissism.

Taking place during one 24-hour span, King Kelly has a speedy plot involving a bag of misplaced drugs which Kelly is forced to recover by an irate dealer. She enlists her friend Jordan (Libby Woodbridge) as well as one of her pay-channel subscribers, a state trooper who logs in under the name Pooh Bear. Still, though, Kelly can’t put down her iPhone camera, turning her own real-life criminal adventure into more fodder for her voyeuristic fans.

King Kelly is presented as if it’s all footage from Kelly’s iPhone, and, indeed, parts of the film were shot by the actress while in character. That said, this is no improvised, figure-it-out-in-the-edit-room mumblefest; Mike Roberts’ script is tightly structured, and the story builds from being a randy comedy of mishaps to a disturbingly trenchant take on the loss of self in the digital age.

King Kelly is a production of the Brooklyn-based production company SeeThink, which also includes Roberts, producer and director Luke Meyer, producer Tom Davis and cinematographer/producer Ethan Palmer. The group seems intent on constantly challenging expectations as their work includes documentaries on artists (Alice Neel, about the portrait painter), conspiracy theorists (the doc New World Order) and live-action role players (Darkon).

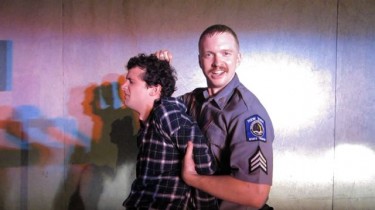

I spoke with Neel and Krause (pictured above) last week about the conception of the film, shooting while in character, and the perils of our digital age.

UPDATE: This article was originally published when King Kelly received its New York premiere, curated by Filmmaker as part of the Northside Festival. It opens this Friday, November 30, at the Cinema Village.

Filmmaker: We’ve seen several movies recently done in a kind of reality style, but yours reminded me of a film from years ago — Man Bites Dog.

Andrew Neel: I was thinking about Man Bites Dog a lot when I first started doing the script with Mike. I always loved that movie, and it’s obviously a film with a very unlikable main character. It’s also a commentary on what media can do to a culture and what an over-mediated culture can do it itself. I think King Kelly is an evolution of some of the concepts in that movie because, in King Kelly, the people are not being put in a movie — they are making their own movie. The thesis, the philosophical thread of [Man Bites Dog] is now evolving in this user-generated world. It’s intensifying. I think we’ve gone somewhere else now that we can create the media ourselves; we have access to the pantheon of celebrity. We may not be celebrities but we can believe that we are. The very fact that we can record ourselves is what makes us exist. Some people only believe in the things they see recorded. It’s like that saying, “Pics, or it didn’t happen.” If we don’t take a picture, it’s not real.

Filmmaker: Were there any models for this character? Either in terms of her personality, or, perhaps, a real-life version?

Neel: The character we modeled [Kelly] on was Cartman [from South Park]. We talked about Cartman a lot. The name “King Kelly” actually came from one of these [amateur webcam] girls. The opening porn scene is based on a number of sites, but the one I was looking on was My Free Cams. And there was a woman was named “King something.” I thought it was interesting that she was claiming male space, and in some ways our character does that too. She’s aggressive, and she tries to get what she wants, albeit by objectifying her sexuality.

Filmmaker: Louisa, did you have your own model for your character?

Louisa Krause: No, I just had that girl in me. [Laughs] I had never seen South Park so I really enjoyed watching Cartman. And then [Andrew] would send me a text like, “Transformers, she loves Optimus Prime!” I just love playing this “king” — she really does rule. She has all of her minions, she gets what she wants and she’s a total schemer. I felt the masculine power. And, yeah, Andrew told me about this one website I could go on to see these girls. I looked at a few of those just to get an idea of what was going on. Some of these women are filming from across the ocean in their bedrooms, and a lot of them don’t even take their clothes off!

Filmmaker: Louisa, did you have any worries about playing an amateur porn star?

Krause: A worry would be for people to mistake me as that character. But when I was playing that character I was like, “Bring it on, feast your eyes on King Kelly!” I was so comfortable working with Andrew, and his energy just fed mine, so it was this really easy project to be a part of.

Neel: Louisa took a lot of risks, especially in this day and age. I mean, apparently nudity and all this stuff is running rampant through our culture, and yet there’s still something conservative going on. You certainly see it in young actresses worrying about showing their breasts. I don’t know if people care about that in France, but here people do.

Filmmaker: There’s that, and the fact that the story doesn’t have a redemptive arc to make things all right.

Neel: The sexuality is not idealized. It’s raw. That sex scene at the end looks like a homemade sex scene because that’s what we wanted it to look like. That’s disturbing to people — people don’t want to see “real sex,” they want cameras dollying over, and [people covered by a] sheet. I think when you do show things in a “grey style,” how it really is, that unnerves people a little bit. And that was the point.

Filmmaker: What does the film have to say about privacy today? Even in today’s social media culture, Kelly is someone who has a radically different conception of privacy. She opens her life to the camera while at the same time fronts a persona for it for most of each day.

Filmmaker: What does the film have to say about privacy today? Even in today’s social media culture, Kelly is someone who has a radically different conception of privacy. She opens her life to the camera while at the same time fronts a persona for it for most of each day.

Neel: I think the film begs the question, “Does she even know where that boundary is? Is there a difference between the person [on-camera] and the person [off]?” That kind of bifurcation of self is really difficult to navigate, especially for a young person.

Filmmaker: I love that the film doesn’t try be a story of redemption.

Neel: We were told to do that but we didn’t!

Filmmaker: So you never thought, here has to be a sweeter, more “human” core to this character of Kelly?

Neel: There were always people talking about that kind of dynamic — you know, “Who’s likeable in this movie?” We didn’t do that. But, I like King Kelly! I think she’s a really funny, hyperbolic, American puppet of sorts.

Krause: I read the script, and I thought, wow, I would love to play such an unlikable character — this would be a real challenge. I believed in what the film was doing, this commentary on extreme internet culture. I believed in the shocking moments of the film — that’s why I fully committed to them. What I found attractive about Kelly is she’s still holding on to her phone at the end of the movie. The [camera] phone is her power; she’s still shooting herself after all this messed-up stuff has happened. I believe she’s an extremely admirable character in that sense because she’s still holding on to what she believes in even though she doesn’t know who she is. I did know, going into it, that she’s an unlikable character, but she’s funny too — she’s a character you can love to hate.

Neel: I don’t know if there’s redemption for her. I wanted things to be open-ended at the end of the film in a narrative sense. I felt like I’d given the audience enough of a story so that I could get away without building that classical, “we figured ourselves out” [conclusion]. Which can be very valuable sometimes but also can be just synthetic and silly. I think in this movie redemption isn’t real point.

Krause: The movie happens in such a short time too — just a night and a day.

Filmmaker: Louisa, were you actually shooting some of the movie?

Krause: Yeah, I shot most of the film!

Filmmaker: Were you thinking about your shots as if you were the film’s camera operator, being conscious of the image, of composition? Or were you just shooting the way your character would?

Krause: I saw it as an extension of the character. I wasn’t worried about technical stuff. But a week before we started shooting we had [camera] lessons and blocked out some scenes with the d.p. I actually made the great switch — I used to be an Android person and now I’m an iPhone person. I was practicing even when I was in L.A. before the film. And [after the shoot], it took me a while to get over making these obnoxious videos. Even after shooting, I kept wanting to shoot. I was visiting my brother again in L.A. and he was shooting up these rockets and I would make all these obnoxious videos of him and send them to Andrew.

Neel: We would do rehearsals using the phone, making kind of sketches, which was cool. To speak to the complexities of shooting that way, it’s kind of an actor’s dream. The camera doesn’t exist, it’s part of the scene. Often we would clear the set and because of the technology and the 360 shooting we couldn’t monitor what was happening; we could just listen [from outside the room]. Ethan, the d.p., and I would be at the door like, “What’s happening in there? What are they doing?” That made it kind of challenging because we had to choose whether to review the take or just do another one, which took roughly the same amount of time.

Filmmaker: When you were casting the film was Louisa’s ability to operate the camera something you considered? Because it seems to me like you could have cast an actress who would have been totally incapable of operating the camera.

Neel: No, but she turned out to be great. When Susan [Shopmaker] and I were doing the auditions for Kelly, we gave a phone to people, which actually freaked some of them out. But we were very worried about the jiggle effect. I think most people don’t have a problem with it, but a few people might think the film is too shaky. I watched The Blair Witch Project before shooting and thought, we gotta do better than that.

Filmmaker: Did you do any image stabilization?

Neel: We did. That’s why a good portion of the movie was shot with a small consumer camera [instead of an iPhone]. It was a Cannon Elph, and it costs about $200. Unlike any other camera that size it has a gyroscopic stabilizer.

Filmmaker: But you did use some iPhones?

Neel: We did, because the iPhones were in the scenes. They were a prop that had to be in but the film, so we intentionally shot with them. Sometimes the d.p. would be operating for Jordan (Libby Woodridge), but she would have an iPhone too so we could do multi-angle. What we didn’t want to do is shoot with the weird depth of field [of a professional camera]. It always had to look like a camera phone. I hate how some films “fake the dirty.” They put a little “record” symbol at the top of the frame and I’m like, yeah, “That’s really 35mm.”

Filmmaker: We haven’t talked about the state trooper character, Pooh Bear. I found him fascinating. He starts off not wanting to be on camera but winds up going along with it.

Filmmaker: We haven’t talked about the state trooper character, Pooh Bear. I found him fascinating. He starts off not wanting to be on camera but winds up going along with it.

Neel: This subject matter has interested me since I wanted to make movies ten years ago. I have two other movies that I’m trying to make that are about internet identities. I almost made a movie about a Pooh Bear-type character, the same story [as King Kelly] but from the other side. There’s real tragedy in that guy. When you have this concept of who somebody is and you then confront that in reality and it’s incongruent with your perception of how they’re supposed to be, it can be tragic. And the thing is, he buys in!

Filmmaker: And he’s a cop, so he should be especially concerned about being on camera.

Neel: Cops have cameras on them all the time, and they do things like having sex on the hood of their car, beating guys up, and it’s like, the camera is running! It’s not like most cops are running around doing horrible stuff, but some cop just shot some dude in the back of the head, and it’s on camera! And this ties into the discussion about our perception of reality. Does the camera muddle our sense of what is happening or not happening? You see [Pooh Bear] fall into Kelly’s creative reality — I believe someone would do that.