Back to selection

Back to selection

From the Archives: A Hard, Wonderful Look at the Movies in Manny Farber’s Film Class

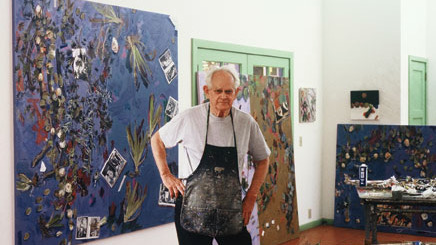

Manny Farber

Manny Farber This piece by filmmaker Barbara Schock appeared in our Summer, 2005 issue.

The phenomenal painter, teacher and film critic Manny Farber called his film class “A Hard Look at the Movies.” It was the first upper-division college class I took. I’d transferred from a small college in the Midwest to the University of California at San Diego, and I’d never seen a foreign film, unless you count the Sergio Leone westerns. We watched the following films in a 10-week period, and it turned the way I looked at movies upside down: Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Max Ophuls’s The Earrings of Madame de…, Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: the Wrath of God, Joseph Lewis’s Gun Crazy, Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout, Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy, Werner Schroeter’s The Death of Maria Malibran, Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le fou and Les Carabiniers, John Boorman’s Point Blank, Eric Rohmer’s La Collectionneuse, Joseph Losey’s Accident, Robert Aldrich’s The Grissom Gang, Luis Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid, Frank Borzage’s Man’s Castle, Nagisa Oshima’s Diary of a Shinjuku Burglar, Jean Cocteau and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Les Enfants terribles and several Buster Keaton films.

The first class I attended was packed and there was a circusy feeling in the air. It was rumored to be the last film class Manny would ever teach. People said he’d grown increasingly disillusioned with teaching film, that he preferred teaching his smaller painting classes. Manny was cranky — the story was he’d recently quit drinking. Supposedly in the old days he drank scotch up in the projection booth with the student projectionists.

Manny had a somewhat adversarial relationship with his film students. He didn’t want the class to be like basket weaving, something you took to satisfy your visual-arts requirement. Partly to thwart those looking for entertainment, he never showed a film straight through, a practice that annoyed many. Instead he’d screen one or two reels of the films in the weekly class, often out of order, sometimes stopping the film to replay a part. If you wanted to see the whole film you could watch it in the sections run by his teaching assistants, which was time-consuming if you had a full class load. Manny would get disgusted if anyone was talking in class, abruptly end his lecture and throw up a reel.

But most of us were enrapt because Manny’s lectures were mesmerizing. Considered by many to have reinvented film criticism with his brilliant, electric prose, Manny had a similarly inventive — and tremendously entertaining — manner of speaking. In vivid, staccato sentences (sounding like a cerebral Edward G. Robinson), he took a run at films. He was terse but rhapsodic; non-academic but deeply analytic. Drawing on a vast range of references to other art forms and with his keen grasp of the times, Manny always got at the guts of a film.

It was fundamentally the painter in Manny who urged us to “look hard at the frame.” He contended that a filmmaker, much like a painter, disclosed himself in a single frame. Manny had us focus on everything in the frame but the subject of the shot — what he termed the “negative space” — like the color and lighting, the scenery, the dialogue, the camera angles, where the character entered the frame, how the camera moved to pick up the smallest detail. Manny favored what he called “termite” artists, filmmakers who aimed not at product but who were interested in the activity of “burrowing into their media.” He wanted us to be termite critics, to burrow into the corners of the frame, where much would be revealed about the filmmaker’s intent.

Being a painter, he analyzed a film as though it were a moving collage of many elements, and those elements interested him more than the story the filmmaker was trying to tell. Sometimes he would run a scene backward and without sound so that we could discuss its visual components. But that surface examination was only part of his approach. While Manny wasn’t much interested in analyzing a film’s plot, he did want us to consider the cultural, historical and artistic impulses behind it. (Of course, it would have been pretty hard for us to analyze a film’s narrative without having seen the whole film.) Manny taught me more about film than anyone.

He called Double Indemnity a “low-down movie,” he talked about how singular and brilliant Wilder and Raymond Chandler’s dialogue was, how it kept cheapness and corruption in its focus at all times — he said the film had a “diseased attitude about disease.”

He described Out of the Past as a nasty middle-class tragedy with a melodramatic sense of light and dark: it was “chiaroscuro with a vengeance.” He explained that The Earrings of Madame de… was a social documentary about the bourgeois that caught its characters in a “dappling of life.” He said that Fassbinder had an eye for domesticity and that he used an “apartheid” effect in his interracial love story Ali: Fear Eats the Soul to “pin the characters with lighting.”

The severe up and down angles in Losey’s Accident made the scenes “prying and covert,” turning a story about social conscience into a thriller, a film whose characters chopped away at each other in fragmented sentences, in “mutilated, savage acrimony.” The characters in Boorman’s Point Blank were not people but puppets in a languid, sensual plastic world “engulfed by the decor.” Aldrich’s movies contained “marred” people, and Aldrich cluttered up his frames of The Grissom Gang with garbage so that the characters were forced to “knife through shit” and live life at a “cesspool level.” Losey, Boorman and Aldrich made “entertaining, degenerate” films about “self-serving, greedy people” who didn’t have much affection for one another “unless it was perverted.”

Manny’s language was hard-boiled — sometimes it felt as if he were going to get into a fistfight with the film he was critiquing. You never really knew where he came down on the films, it wasn’t a “thumbs-up, thumbs-down” kind of criticism, although there were directors he seemed to love, like Buñuel. He said that Buñuel’s films were haunting and forbidden, something inexpressible and private, like your favorite pornographic novel.

Manny loved the actors too, especially the “bit” players, but he rarely talked about how well they played the role or how they sought an emotional truth. He focused on the actors’ gestures, how they occupied the frame, the “psychological space” the actors inhabited. In Les Enfants terribles, Melville and Cocteau’s story of a doomed brother-sister relationship, a high angle on the siblings in their “dyspeptic, gloomy, dun-colored” bedroom made them seem like “chess pieces in a hopeless drama viewed by God.” Manny was interested in the actor as a living piece of the whole production design.

In his insightful preface to Manny’s book of film criticism Negative Space, Robert Walsh writes that Manny was a “seer about the relations between film and its historical moment” — which is very true, and was part of his genius as a teacher of film.

In one of his most brilliant lectures, Manny described Walkabout as being “sinister and perverse” and emblematic of the films of the 1970s. He talked about the voluptuousness of the 1970s, about how one thing led to another and “things just happened, man.” Manny said that Roeg’s endless dreams, focus changes, off-angles, his going from macro to micro shots in Walkabout showed the multiplicity of choices for the human being in that decade.

Manny talked about the grand sense of terrain in Aguirre, the Wrath of God and said that even when a Herzog shot was standing still, it still had a “whoosh.” He mainly used Aguirre to talk about the director’s subversion of narrative form, as he did with Godard and Oshima. Manny explained that most films try to impersonate life but that Godard mocked and picked on life “like a sniper.” Oshima was a collage artist who “at all costs wants to deny you a plot.” While Herzog was a more compassionate filmmaker, he inhabited an “irrational movie area” where there was no space for human relationships. Herzog seemed to have a soft spot for “demented people,” but he treated actors as pictorial ideas rather than actual people who needed “feeding, or anything.” All three filmmakers rejected old-fashioned, “boxed-in” drama and relied instead on other art forms to create their films, challenging us to find their motivations, which were “well worth digging for.”

Manny said there was a certain sexual sadism to be found in the long takes in Gun Crazy (I understand that better now than I did at age 19). He helped us understand why we can frequently rewatch Eric Rohmer’s movies even though they appear to be simple. He said Rohmer has an ability to sustain natural talk and keep the viewer intensely involved in what’s said, because thoughts, not actions, are important in his films. That Rohmer’s naturalistic dialogue and lighting style (a feeling of “nature caving in from sunlight”) stemmed from Rohmer’s belief that any passage of time reveals a person — it doesn’t have to be a big moment. He also called Rohmer a voyeur and a “soft-porn artist.”

Manny’s final lecture that year was on Buster Keaton. He talked about Keaton’s subtle, quiet, profound grace, his feeling for other people and sense of environmental proportion. I think he taught Keaton as a kind of respite from the other filmmakers. Keaton’s camera wasn’t “parasitic” — it didn’t chase the characters when they exited the frame; it held on the lovely outdoor scenery until someone else came along, giving the films a “comfortable, luxurious” feeling.

Thankfully, my first class with Manny turned out not to be his last. He taught for another decade, continuing to expose his learners to the latest European filmmakers, such as Wim Wenders, Marco Bellocchio, Marguerite Duras and Jean-Marie Straub, and continuing his love affair with the American “B” directors he’d been an early champion of, like Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray and Raoul Walsh. Sometimes I think Manny read too much into avant-garde filmmakers like Straub and Duras, while giving short shrift to more established European filmmakers like Fellini. But he took risks in teaching and championing both emerging and forgotten filmmakers like Fassbinder, Borzage and Aldrich. As a result his students were steeped in dynamic European and classic underground American cinema.

With remarkable wit, feeling and insight, Manny introduced us neophyte film students to grown-up, sophisticated ideas about the artistic process, pop culture, the human psyche and even sex. To those of us fortunate enough to study with him — people like novelist Rex Pickett, critic Carrie Rickey and filmmaker Michael Almereyda — it is wonderful news that he is still around, painting beautifully and creating film series (for P.S.1/MoMA and the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, which both also recently showed retrospectives of his paintings).

Most of my friends think I am too critical of films, and so I tell them about Manny. He didn’t merely give me the license to criticize but the means. As a filmmaker living in Hollywood, I find it easy to get distracted by the commerce, by what Manny called the “hard-sell”; Manny puts me back in the dark, watching the films unfold and learning from that human, pleasurable experience. In a time when what is hip is marketed to us in more sophisticated ways than ever, Manny points us to the real outsiders in the way they approach the film frame. Like Edward G. Robinson in Double Indemnity, I feel I’ve got a little man inside me, with a voice a lot like Manny’s, who helps me identify a fake. While Manny can be a curmudgeon about films, he is also generous and inspiring, and he’s not a snob. He loves comedies, Laurel & Hardy, gangster films — all that’s unpretentious in the “movies.” I think about him at least once a week and about the great influence he’s had on how I view film art.