Back to selection

Back to selection

Blast of Silence: Independent Filmmaking, Then and Now

1961 — I drove up to the gate of 20th Century Fox studios and hesitantly gave my name to the guard. I had an uneasy moment watching him look at a pad before he greeted me with “Good morning, Mr. Baron” and waved me forward. I steered my car under the elevated train set of Funny Girl and passed several soundstages to a parking area with my name in large white letters written on it. I got out of my car and paused to look at the surrounding studio activity, and the question. “How the hell did I get here?” occurred to me, because just two years earlier I was a sometimes employed high-school dropout living in New York.

The fact is, in 1958 I was working as a freelance comic book artist and taxi driver. I also designed some sets for a low-budget exploitation film producer, Barry Mahon. In January 1959, he invited me and four of my friends to come to Cuba to work on a non-union low-budget film. Although I had no previous experience actually working on a film, nor did my friends, we were excited by the idea of going to Cuba. So, in February 1959, I and the rest of the crew left for Cuba.

We arrived only weeks after Cuba’s new leader, Fidel Castro, had taken over. I then learned that Mr. Mahon, the producer/director, had inveigled Errol Flynn, whose career was on the down-slide, to be in the film

I found it to be an extraordinary experience, which I detail in my memoir, Blast of Silence. Briefly, as bizarre as it may seem, Mr. Mahon never had a script depicting actual scenes. He would gather me, the cast and crew, and drive to a location where he would set the camera up and give the actors instructions as to what to do. Even though I had no previous on-set production experience, it did not seem to make sense; but it was a fun job and I was happy to be working on a 35mm film. By the time the shoot came to an end I learned that Mr. Mahon’s moviemaking knowledge did not go beyond the loading of film into a magazine and camera. (Years later, I learned that he was a World War II flying ace, POW and principal character in the actual Great Escape). As crazy as the Cuba experience was, I saw the possibilities of using a camera and making my own film.

In the fall of 1959 I returned to NYC and decided to make my own movie. Making an independent feature film then was expensive, extraordinarily technical, and if the film was completed the chance of it getting national distribution was equal to the odds of winning the Triple Crown in racing. Ignoring these facts, I decided to go ahead anyway. At the time it was a challenge thought to be undertaken by the psychologically underprivileged or unrealistic dreamers. Today, if one decided to make an independent film, the fundamental ingredients necessary could be described in one frame of an iPad. In 1959 it would have required many pages of a notebook to list the necessary ingredients. Following is a list of basic technical equipment and facilities necessary for making independent film then and now.

In 1959 the essential ingredients for shooting a film were:

A script.

A rented 35mm camera (to buy one would cost $100,000), 400 ft load magazine. 35mm film and raw stock.

Cable, lights, dolly, tripod.

Rental of a laboratory for printing and screening dailies.

An editing room with the rental of a Movieola machine and editing equipment.

Rental of a sound recorder with microphone and cable.

A truck or vehicle for carrying equipment.

A cast, and crew of at least five people.

In 2013, the following is all that’s fundamentally necessary:

A script;

A digital camera (an excellent one can be purchased for as little as $600);

A boom or wireless microphone;

Little or no lighting equipment;

A laptop for editing and viewing;

An automobile with a trunk to carry equipment;

A cast, and crew of a minimum of three people (a small advantage)

I rented a $20 per month apartment and started writing the script which I named Blast of Silence. I also drove a taxi to help pay for my fundamental expenses and connected with Mel Brody, an old chum from grade school who, at the time, was converting an old firehouse on 46th Street into a soundproof studio where some commercials were shot (in which I sometimes designed sets). I also befriended people at the “Camera Equipment rental company,” which proved to be invaluable for the production of my film. When I completed the script, Mel Brody and I had $3,000 with which we intended to start making the film.

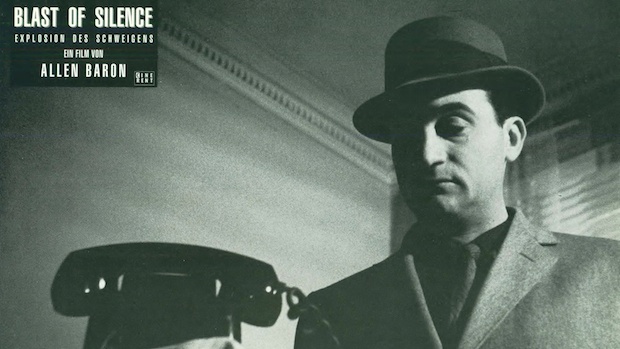

Bert Schneider, the owner of Camera Equipment Company, agreed to lend us a 35mm Arriflex camera for a few days. (Later I rescued a camera from Cuba, details in my book.) We bought “short ends” of film at a discount (these were leftover pieces of raw film stock sold by companies as opposed to discarding them). Our plan was to shoot five or 10 minutes of the raw stock we had acquired and hope to attract investors. When I failed to get Peter Falk to play the lead (he was a barroom friend) Mel suggested that I act the part of Frankie Bono in the film. This was not my original intention, but I had some acting experience, and after serious consideration decided that if this is what it took to make my own film, I would do it. My screen test consisted of my acting in a brief scene using a telephone in Grand Central Station. We thought my performance would work and the screen test was used in the completed film.

Bert Schneider, the owner of Camera Equipment Company, agreed to lend us a 35mm Arriflex camera for a few days. (Later I rescued a camera from Cuba, details in my book.) We bought “short ends” of film at a discount (these were leftover pieces of raw film stock sold by companies as opposed to discarding them). Our plan was to shoot five or 10 minutes of the raw stock we had acquired and hope to attract investors. When I failed to get Peter Falk to play the lead (he was a barroom friend) Mel suggested that I act the part of Frankie Bono in the film. This was not my original intention, but I had some acting experience, and after serious consideration decided that if this is what it took to make my own film, I would do it. My screen test consisted of my acting in a brief scene using a telephone in Grand Central Station. We thought my performance would work and the screen test was used in the completed film.

I knew that New York City could not miss as a background for the film, and I also thought that only gray days would add a grim tone. We decided to shoot the ending scene first, out of sequence, to use as a teaser for potential investors. When we arrived at the location in Jamaica Bay with me, two actors and the crew, it was a sunny day I thought that would never work for the general look of the film and the specific killing scene which required that I got shot and fall into the bay. So we waited (10 days) until the weather got cold, grey and stormy and shot the scene with me falling “dead” into the water. We used the last of our raw stock for the scene.

That night while I was recovering from my ordeal, I was in Downey’s restaurant eating dinner. I explained what I had been doing to several men that day and they asked to see what we shot. When they saw the footage they decided to invest in the film. We naïvely traded 50% of ownership of the film to the three of them in return for $18,000 which, with deferments, we thought would be sufficient to complete the film.

We decided to shoot the film “guerrilla fashion,” which meant shooting at locations all over the city without any permits. Among the things, on the very first day, the camera was mounted on a tripod designed for 16mm camera and it toppled over and fell. Shooting in the hallway of the building we had to stop to allow tenants to pass by. We often had to bribe cops (with our lunch money). We continued filming a scene on a barge in the East River while a watchman threatened to arrest us for trespassing. The police tried to arrest us for having a hidden camera in our Volkswagen bus because they thought we were spying on their illegal activities.

In spite of these difficulties, we subsequently completed the film. One of the investors immediately contacted a relative who worked for Universal, who then purchased the United States rights to Blast of Silence for $50,000. We later regretted this hurried transaction because 20th Century Fox subsequently offered three times that amount, but unfortunately, the verbal deal with Universal was already made. With hindsight, I realized many mistakes were made after we completed the film, but we were very naïve and just thrilled that a major studio was going to release our little film. A positive aspect of it all was that I was put under contract, which began my 50-year career in film and television.

Attempting to make an independent film today as opposed to 1959 would present a far different set of problems. For one thing, in 1959 I doubt if more than a half-dozen independent movies were attempted to be made. Today, because of the use of a digital camera, literally thousands of independent movies are being made. While I’m sure that among the many thousands there are probably some very excellent movies, the crowded field makes it very difficult for distributors to make a selection. Today, anybody can go into a store, purchase a digital video camera and start shooting a movie. This was absolutely impossible in 1959 because of the use of film and expensive equipment that was necessary to shoot a movie. An additional point that emphasizes the difference between then and now is the fact that in 1959 I doubt if there were more than half a dozen film festivals in the world. Today there are literally hundreds.

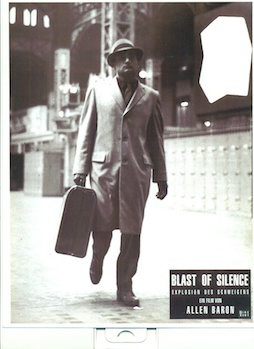

Allen Baron directed the cult classic 1961 film, Blast of Silence, and went on to have a successful 25-year career in Hollywood and television. His critically-acclaimed film noir is discussed in his newly released memoir, Blast of Silence. Baron has directed 250+ television episodes for numerous hit shows, including Charlie’s Angels, Fantasy Island, Love Boat, The Brady Bunch, The Dukes of Hazzard, M*A*S*H, and many others. Baron was a director, producer and writer foe 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., and Allied Artists, Universal, and CBS. His feature films include Blast of Silence, Pie in the Sky; Red, White, and Busted; and Foxfire Light.

Baron was born and raised in Brooklyn. He grew up poor during the Great Depression. The son of Polish and Russian immigrants, Baron quit high school on his 16th birthday and took a job with the War Department, working on the atomic bomb. At the age of 17, he joined the Navy during World War II. At age 19, he enrolled in the School of Usual Arts in New York to study illustration. Baron had many odd jobs for several years, including driving a taxi and drawing for several comic book publishers. He enrolled in his first acting class at age 25, where he met his wife. In 1959, he began filming Blast of Silence.

Blast of Silence: A Memoir by Allen Baron is now available from Parker Publishing.