Back to selection

Back to selection

Editing Today: Beyond the NLE

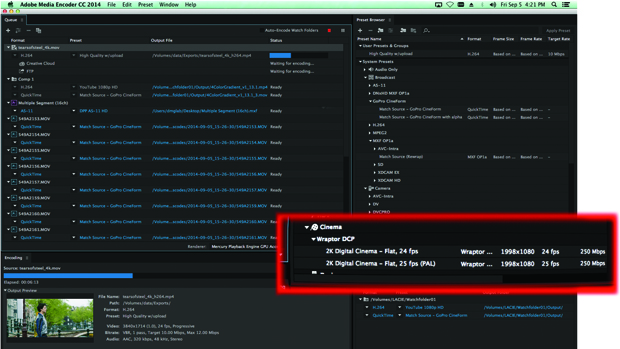

QuVIS Wraptor 3.1 plug-in (enlarged section) enables do-it-yourself 2K DCP in Adobe Media Encoder CC (Photo courtesy of David Leitner)

QuVIS Wraptor 3.1 plug-in (enlarged section) enables do-it-yourself 2K DCP in Adobe Media Encoder CC (Photo courtesy of David Leitner) David Lean once called editing the soul of filmmaking. Today it’s more like the Mission Control.

You’ve got to understand pixel counts, bit rates, bit depth, color sampling, sampling frequencies, frame rates, codecs, RAW files, deBayering, audio channels, waveform displays, vectorscopes, audio levels, LUTs, proxies, file-wrappers, Log gammas, XML, titling, effects — need I go on? Arcane stuff that used to be the domain of video engineers with EE degrees.

To ensure a smooth and efficient postproduction “workflow” (term borrowed from I.T.), you must know about cameras too: which frame sizes they capture, which codecs they employ, which gammas they apply, which file wrappers they add. Speaking of I.T., you must know how much disk storage you’ll need for both media and render files, how blazingly fast your drives must be (RAID 0 anyone?), and how fat the pipes must be — FireWire 800, USB 3.0, eSATA, Thunderbolt 1 & 2, in order of faster throughput.

As you ingest camera footage, you must decide how to organize it for the edit and beyond. Will it be backed up? How much will be archived? To optical discs, hard drives, linear tape, the cloud? How will you keep track of everything during post? How will someone in the future figure out what’s what, and where?

This is light years from cutting 16mm, where editing meant Iron Age chopping plus tape-splicing skills and perhaps a knack for rewinding. Today’s nonlinear editing (NLE) apps can’t stop morphing and metastasizing to accommodate ever-sprawling complexity. Not to mention the demands of new, more efficient codecs like HEVC (H.265) and Sony’s XAVC, new frame sizes like UHD and 4K, new camera gammas (that milky gray look) requiring look-up tables (LUTs) for proper viewing, and new output formats for theatrical and streaming.

This is one reason Apple attempted to rethink, distill and streamline NLE functionality when they introduced 64-bit FCP X three years ago, to howls of indignation. True, early FCP X was undercooked and lacked basics like EDL, OMF, multicam and FCP 7 compatibility, but I think the underlying complaint of many FCP X naysayers was, and remains, rooted in the significant investment in time and experience needed to master a modern NLE, no less adopt a radically new paradigm. Most FCP editors simply wanted a faster, brawnier version of what they already knew.

Since its debut in June 2011, FCP X has undergone 13 free updates, averaging one every three months, distributed online by Apple’s App Store. Multicam, broadcast monitoring, XML and 4K support are now old news. With the arrival this year of the cylindrical dual-GPU Mac Pro, for which FCP X is expressly tailored and vice versa, it’s clear Apple remains serious about pro video. In fact, at NAB they boasted over a million paid seats for FCP X, more than the previously installed base for FCP 7. Yet, three years on, a significant number of editors cling to no-longer-supported FCP 7.

Tallying FCP 7 and FCP X users (Mac only), it’s safe to say that Apple still commands a leading share of the pro NLE market along with Avid and Adobe (Mac, Windows both). Other extant 64-bit pro NLEs, worthy challengers all — Sony Vegas Pro 13 (Windows) with its native handling of pro codecs like XAVC, P2’s AVC-Intra, HDCAM-SR, ProRes, and REDCODE RAW; Grass Valley EDIUS Pro 7 (Windows); Lightworks 12 (OS X, Windows, Linux); and Boris FX’s Media 100 (OS X) — get relatively less traction, so I’ll focus first on developments within the AAA juggernaut.

NLEs long ago met their basic task of cutting and pasting clips in timelines. FCP X represents a unique effort to enlist the power of today’s 64-bit computing to also cement sync (magnetic timeline), preserve every last keystroke from crashes (autosaving, auto-archiving, Time Machine), accelerate editing rhythm and productivity (background rendering), simplify shopkeeping (Finder-level media management, extensive metadata tracking) and exploit core OS technologies (Core Animation) to enliven the user interface. FCP X’s latest innovation, the Library, is a single master file that bundles project timelines, render files, and media. Everything you need to reconvene a particular edit elsewhere.

You can do these things when you engineer both software and hardware. Take app amalgamation. With FCP X’s introduction, gone were Color, Soundtrack Pro, and DVD Studio Pro. Their key features were absorbed into FCP X. (Or discarded. No way to set region codes or tailor splash screens when burning DVDs directly from FCP X.) In my view this represents progress, as I dislike exporting and importing clips between apps, i.e., external “round-tripping.” Why can’t a single editing app do everything related to editing and finishing? In fact, one of the recurring complaints about FCP X is that there is no way to send a project or clip to Motion from within FCP X, or open a Motion project in an FCP X storyline in order to update an effect.

This is exactly what Adobe has achieved by linking the latest versions of Premiere Pro CC and After Effects CC. You can create a complex text composition in After Effects CC, then output it as a template, open it in Premiere Pro CC and continue to modify it without having to return to After Effects. Using Adobe’s Dynamic Link, you can create a mask in Premiere Pro CC, automatically animate the mask’s position by tracking a moving subject, then, when more finesse is needed, send the clip with mask and keyframes to AE for precise adjustment.

To be fair to FCP X, motion-effects plug-ins already exist inside FCP X due to FxPlug 3 architecture, which exploits the power of OS X’s Core Image along with GPU optimization. FxPlug 3 enables motion, transition, “generator” — grids, color bars, t.c. burn-ins — and title effects authored in Motion 5 to be published as plug-ins, then imported into FCP X for direct use on the storyline. A youthful Internet community of FCP X users creates and freely swaps collections of these FxPlug 3 effects, which a little bit of Googling will uncover.

In September at Amsterdam’s IBC, Adobe also unveiled a much-needed make-over of their graphical user interface. Taking cues from FCP X for a tighter, more modern appearance — less 1998, more 2014 — Premiere Pro’s new look supports HiDPI (high dots/inch) monitors like MacBook Pro’s Retina Display and similar displays in Windows 8.1 devices. Also new are dynamic “search bins” that filter clips by metadata even as fresh clips are added, a new timeline view that displays multiple timelines at once, clip icons of little windows that are scrubbed for preview and fast selection and auto-backup of Premiere Pro projects to Adobe Creative Cloud.

CC, of course, denotes Adobe’s Creative Cloud services, to which, in 2012, Adobe moved most of its creative apps including video. Unlike FCP X’s App Store updates, which are free, access to Creative Cloud apps and their updates requires a monthly or yearly subscription, meaning that, like FCP X’s updates, you’re always using the very latest version of an app. To be clear, Adobe’s CC apps reside on your computer and you need only go online once a month for Adobe to verify your subscription.

CC contains at least 15 specialized apps, including Photoshop, Premiere Pro, After Effects, Audition, and SpeedGrade. The full slate, with 20GB of cloud storage thrown in, is $74.99/month or $599.88/year, which comes to $49.99/month if subscribed for a full year. There are also Single App subscriptions at $19.99/month with an annual contract. In other words, Adobe has pointedly not taken the path of amalgamating its NLE with other apps.

Of particular note is Adobe Media Encoder, a standalone answer to Apple’s Compressor available via Creative Cloud as a complement to Premiere Pro (not à la carte). Earlier this year Adobe announced the licensing of QuVIS Wraptor 3.1 (Mac, Windows) as a Media Encoder plug-in to enable do-it-yourself DCPs. Talk about sweetening the deal! What Creative Cloud doesn’t offer, however, is a DCP viewer to avoid renting an expensive theater with 2K projector to check your homebrew DCP. One answer is DCPPlayer 1.0, Mac-only software you can buy or rent directly from QuVIS. (A Mac version of Wraptor 3.1 is also available as an Apple Compressor plug-in.)

How is Creative Cloud doing? In June Adobe announced 2.3 million subscribers, with CC responsible for 53% of the company’s revenue. Of course with throngs of photographers signing up for Photoshop, it’s hard to break out the subset of those who are primarily video editors.

(Adobe CC apps are now happier on the cylindrical Mac Pro thanks to OS X update 10.9.4 and Premiere Pro/After Effects bug fixes earlier this year. Resolved was an issue caused possibly by DaVinci Resolve’s CUDA drivers installed in the new Mac Pro, which doesn’t use CUDA but rival OpenCL for its AMD GPUs.)

For those inclined to march to a different drummer, there now exist two unconventional but remarkably capable NLE contenders, as I described in Filmmaker a year ago in “Autodesk Smoke 2013 – Super NLE?“

As NLEs, Autodesk Smoke 2015 (Mac) and Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve 11.1 (Mac, Windows, Linux) reverse the example of FCP X absorbing apps like Color. These are post finishing/EFX and color grading giants that have instead absorbed full timeline editing and media management features. In other words, they’re sandboxes you don’t have to leave. While both provide broad support for exporting and importing of clips and project timelines to/from other apps, they are complete and insular ecosystems that make round-tripping seem primitive.

Smoke is renowned for sophisticated node-based compositing (shares DNA with siblings Flame and Inferno), just as DaVinci Resolve is renowned for its node-based color grading. Working with nodes is like working with layers in Photoshop: you non-destructively tweak the contents of a particular clip’s effects node without altering other effects nodes you’ve created, or color decisions you’ve made. Like FCP X and other 64-bit NLEs, renders occur silently in the background, causing effects to be available almost instantly.

As a comprehensive editing/finishing environment, Smoke brings extensive color grading tools, while DaVinci Resolve offers OpenFX plug-ins (an open-source standard usually found in Windows). Notably, at IBC in September, Blackmagic Design announced the acquisition of eyeon Fusion 7 (formerly Digital Fusion), a top node-based compositing program popular with high-end Hollywood visual effects houses. If Blackmagic’s democratization of DaVinci Resolve is any indication, a port of Fusion 7 to OS X awaits, then a vertiginous price drop that seeds Fusion “Lite” across the DIY desktop spectrum. What if, instead, DaVinci Resolve and Fusion merge into Blackmagic’s version of Smoke?

As it stands, Smoke 2015 and DaVinci Resolve 11.1, both node-based workflows crossed with full-fledged NLEs, impose significant learning curves. (You WILL study the manual. Frequently.) But you’ll find 50 new tutorial videos on Smoke’s YouTube channel to illustrate its user interface and capabilities, while Blackmagic Design’s website hosts detailed video overviews of editing and color grading with DaVinci Resolve 11.1. Not to mention those countless YouTube how-tos from fellow users.

Moreover, you can test-drive both NLEs for free. Smoke 2015, available by subscription only — monthly $185, quarterly $460, annually $1470 — offers a 30-day free trial. Educators as well as students are eligible for a free long-term license. Blackmagic Design tacks in a different direction, offering full DaVinci Resolve 11.1 (requires dongle) for $995 but DaVinci Resolve Lite 11.1, which delivers 95% of the full version, for free. This includes all formats up to UHD (3840 x 2160). What you sacrifice with the free version is 3D stereo, true 4K (4096 x 2160), advanced noise reduction, and the possibility of collaborative, long-distance editing.

Free versioning is an intriguing strategy. As in the case of DaVinci Resolve Lite, it can cause widespread adoption and de facto mainstreaming, which otherwise would not have occurred. Lightworks 12 has recently adopted a similar path, offering a Pro version by subscription for $24.99/month, $174.99/year, or $437.00 outright, but also a free version that virtually matches the full version. Its single limitation is 720p MPEG-4 output. Apple, of course, split the difference with FCP X, slashing the price of FCP X by two-thirds compared to FCP 7, to $299.99. All this NLE low-balling brings smiles to us little guys.

The granddaddy of NLEs, Avid’s Media Composer (Mac, Windows) retains its one-time, perpetual license, now $1,299, but recently added subscription rates of $74.99/month or $599.88/year, which amounts to $49.99/month with a year’s subscription (same rates as Adobe Premiere Pro CC).

Speaking of collaborative, long-distance workflows, the latest selling point for NLEs is multi-editor timeline sharing based on mutual access to media “assets,” either on a local server or over the Internet. Apple’s bundled Library, by consolidating both project files and source media into one big container file — like a briefcase with a handle — facilitates non-simultaneous sharing (also simplifies later archiving). The same Library can be stored or moved between remote servers and SAN volumes or hand-carried by hard drive. Whatever the case, when opened on a Mac with FCP X installed, all resources needed to continue the edit are included.

Adobe, Avid, Blackmagic Design, and Lightworks define multi-editor sharing as real-time collaboration from a distance. Adobe calls theirs Adobe Anywhere; Avid calls their Avid Everywhere; Lightworks 12, Project Sharing; and DaVinci Resolve 11.1 (paid version only), Collaborative Team Work. As demonstrated by Blackmagic Design’s Grant Petty at NAB in April, DaVinci Resolve’s version of collaborative editing enables an editor and multiple colorists at far-flung workstations to simultaneously share the same timeline. As an editor cuts, a colorist might fine-tune already-locked sequences, while another might create power windows to track exposure issues across a tricky traveling shot. For assembly-line film and television post schedules where time is big money, this is pay dirt.

Lastly, how to archive? I’ve been following Sony’s Optical Disc Archive (ODA) system for several years, basically a dozen Blu-ray discs in a cartridge. Disc storage, intrinsically nonlinear, promises fast file access compared to linear LTO-6. The good news is Sony’s claimed 50-year archival life. Bad news is that, at present, street price of an ODA USB 3.0 drive is $5,000 and maximum 1.5TB cartridge is $160. These high costs are obstacles when a single bare 4TB 3.5-inch hard drive is $145, 6TB is $280, and 8TB is shipping already. LTO-6 tapes, which offer 2.5TB — don’t fall for claims of compressed 6.25TB storage capacity, since digital video is already highly compressed — are $72. You’ll need an LTO-6 drive, $2,500-$5000.

Sony’s road map depicts a 3.6TB Generation 2 cartridge by 2016 and eventually a 6TB Generation 3 cartridge. Sony makes a strong argument that ODA is truly archival, eliminating periodic data migration. However anyone who has shot or edited high-end RAW, XAVC, ProRes or 4K knows that 6TB already seems paltry. LTO-7, due in 2015, promises native tape capacity of 6.4TB, while future LT0-8, perhaps 12.8TB.

At present I’m archiving on 4TB bare hard drives with cloned back-ups. A reasonably priced LTO-6 drive with Thunderbolt might change my mind. So far there’s only one, mLOGIC mTape, $3,600, which debuted at NAB. Perhaps I’ll wait a year for LTO-7. Let’s hope by then the industry wakes up and offers us a choice of Thunderbolt LTO drives