Back to selection

Back to selection

The Reagan Years Producer Sierra Pettengill on the Textures of Archival Footage, the Value of Community and Pitching at CPH:FORUM

The Reagan Show

The Reagan Show In the decade after graduating magna cum laude from Boston University, Sierra Pettengill hasn’t wasted much time carving a niche for herself in competitive New York City as an award-winning producer. Originally from nearby Nassau County, she has utilized her wide-ranging interests, innate curiosity, whip-smart instincts and indefatigable work ethic to establish herself rather quickly in an increasingly tough marketplace. She was exposed early on in her career to the PBS model as an associate producer for American Experience’s Walt Whitman (an Emmy Award nominee in 2008), and Triangle Fire, a Peabody Award recipient in 2009. She would partner again with Jamila Wignot, the director of Triangle Fire, to co-direct and produce Town Hall, a feature documentary about two Tea Party members of different generations in Pennsylvania the two filmmakers followed for close to two years. The film was broadcast on PBS’ America ReFramed series. Pettengill’s artistic sensibilities imbued these deceivingly straightforward documentaries with very personal and complex ideas about trying to understand, and thus portray, her protagonists in the context of class – its privileges and its limitations – within which they must work out their own challenges in a continually transforming America.

Partnering with filmmaker Zach Heinzerling, she became producer of his début feature about the 40-year relationship of Japanese painter Ushio Shinohara and his wife Noriko, Cutie and the Boxer. The film won its director a Grand Jury Prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and was also a nominee for Best Documentary Feature at the 86th Academy Awards, an extraordinary accomplishment for such a small, handmade production.

While producing Cutie, Pettengill was also very busy as an archival producer, working on an ARTE France project for French actor, Mathieu Amarlric, as well as the documentary features Teenage, directed by Matt Wolf, E-Team (directed by Ross Kauffman and Katy Chevigny), and James Spione’s Silenced. Her latest project as a producer is The Reagan Years directed by Pacho Velez, whose last film, Manakamana, co-directed with Stephanie Spray, won the Golden Lion at the Locarno Film Festival last year.

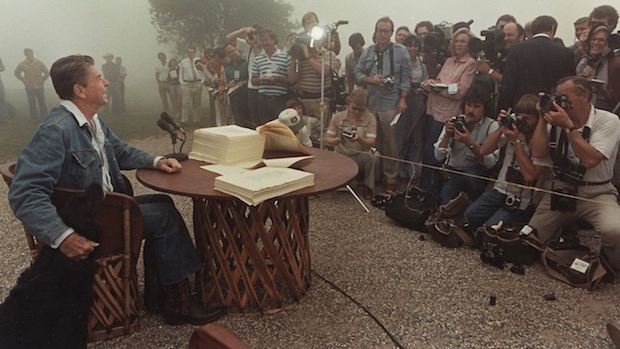

Exploring “a prolific actor’s defining role: Leader of the Free World,” Reagan Years will be entirely created with largely unseen archival footage. Akin to Andrei Ujica’s brilliant The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu, a film that Pettengill tells me has been a huge influence on her and Velez’s writing and research, it will capture the journey from Hollywood to the White House of the US’s 40th President and Commander-in-Chief.

Pettengill and Velez won the Points North Pitch Award and Modulus Finishing Fund grant at the latest edition of the Camden International Film Festival’s Points North Forum this past October. This week at the Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival – CPH:DOX – they will present in the festival’s Forum in front of an international panel of commissioning editors, producers and distributors. There is still as much misunderstanding on the part of American producers as to how the “European model” works for completing nonfiction projects as there is on the part of European producers as to how the “American model” works. So, I wanted to talk to Pettengill about not only her career, thus far, but also her expectations of what she might discover from her counterparts here in Europe.

Filmmaker: Copenhagen will be the first time you’ve pitched at an international forum?

Sierra Pettengill: Yes it will be. I wasn’t part of any of the pitches for Cutie and the Boxer at CPH or IDFA. The pitch [for The Reagan Years at CIFF in October was my very first pitch, and it went extremely well. I don’t know what to expect. It’s also an interesting proposition as to how to speak about Ronald Reagan in front of an international audience.

Filmmaker: I’m always curious about filmmakers’ relationships to their protagonists when working solely with archival material. There are a variety of ways for you and Pacho to portray someone like Reagan depending on which story you want to tell of him and America during the eight years of his presidency in the ‘80s — such a strange and unsettling time in our history.

Pettengill: Both Pacho and I are Reagan babies. I was actually born during the years of the Reagan administration. This encounter with Reagan does very much fit within my broader relationship with archival footage. What I appreciate about it the most is that you’re able to get the texture of a time in a way you can’t experience otherwise. Much of what’s fascinating about watching all the Reagan footage is encountering this ghost of a sense memory I have of my childhood. Some part of me remembers the textures of these places, the sounds; it’s in the quality of the video or film recordings.

Watching it all and attempting to tell people a story of someone who has already had a million stories told about him in this half-remembered or sensory way and to build a relationship has been, and will continue to be, something incredibly fascinating. It’s the overall challenge of working with archival material, in general. It’s difficult to manipulate it in a way that communicates to an audience the things you want them to focus on, the things you want them to feel. When you can draw attention to some sort of textural detail, or something in the frame that communicates something very specific about that time, it can be magical.

Filmmaker: What reverberations or resonances are you hoping to tap into for both people who lived through that time and an audience that wasn’t born yet? What is it about this particular icon that might speak strongly to us now? It’s amazing that American politics is still mired in this incredible idealism, still imbued with the spirit of political campaigns from a more naïve time. It’s kind of eerie. I distinctly saw this in Town Hall.

Pettengill: That’s interesting that you say that because I do think of Town Hall and the Reagan project as really speaking to each other and grappling with the same set of ideas. We’re still sorting through 2,000 hours of Reagan footage so we’ll see how things develop. Not to belabor the point of remembering that he was a former actor, but he was someone who was performing a role, as all presidents do. But he was actively creating this idea of American society as he wanted it to be. This is why I think he was such a successful president and his reputation has continued to be as strong as it is. He painted this picture of the white-picket-fence, ideal America where problems didn’t exist and then sold that to the American people quite successfully. The escapist fantasy the Reagan years symbolizes to us in this archive is so resonant because all of his administration’s public events were documented the way he and his administration wanted them to be. And it is eerie to watch – there aren’t any black people, for instance, or no people of color, except for the occasional NAACP function.

There is a Lynchian quality to some of these scenes. For instance, there is a 4th of July party on the White House lawn from the first year of his presidency. In part because the early years of the Reagan administration were documented on 16 millimeter, there is this dream-like layer to the footage. We see, for instance, this 1930s-themed party with everyone dressed in white outfits, complete with hats. There’s a Model-T people can take rides in, and all of them are white and upper-middle class, all holding these blue balloons, a hazy dream of an America that probably never existed, and definitely did not exist in 1981. That’s what I mean by capturing the textures of a time because the story is as much the presentation of the material as it will be presented as a concrete story arc. As time goes on, from 16 millimeter, the documentation then gets recorded onto ¾ inch tape and Beta by the end, so the footage becomes grittier, more “real,” like news footage. We’re trying to pair that with the idea of reality interceding on the Reagan Dream. It’ll be a big challenge editorially because it’s also as much about the things that will be omitted as well as what’s captured. There’s not much about AIDS, for example. We want to see how we can make those absences really felt. Because there is a real creepiness there we want to evoke of these theatrical set pieces that were an integral part of his administration.

Filmmaker: At CPH there’s always been this obsession with performance in documentary, or the way in which a nonfiction filmmaker distinctly directs his or her protagonists. It’s continuing to be a strong theme in nonfiction.

Pettengill: You spoke to [director and editor] Robert Greene this week.

Filmmaker: I did, and he’s obsessed with it, too. In all of its aspects, it’s something that’s coming to the forefront more and more, and consequently the “pushing of form” becomes a fairly moot point. There’s this imperative on the part of some to concentrate on the quality of the work as a film and less on the preponderance of where it might fit into the genre follies.

In particular, your work shows that the way in which politics and the political arena work is a very rich place to tap into all this because it’s also theater. What pulls you in so that you want to continue to tell stories within the milieu of the political arena?

Pettengill: The impetus in making Town Hall and other things I’m pursuing is that I’m genuinely interested in the gray areas. I think performance helps play a part in exploring that. What’s happening in the liminal spaces is what’s captivating. In Town Hall, we had a presentation of a group of people that were having a giant impact on American politics. It’s very easy to disparage them or think they’re idiotic, but there’s something very real happening to them. To try to get inside that was the plan for that project and to paint a portrait mostly using grays. What was interesting in attempting to do that is that we had characters that see the world in a very black and white way. The challenge was to take a couple of people or a group of people that an audience is going to be predisposed to be against and work against those expectations. Also, hopefully, we’re challenging our own ideas of who our audience is, the assumption being that the majority of them are white, educated, middle-to-upper-middle class Democrats. There are preconceptions all around. It’s hard to talk about without sounding relativist, but the hypocrisy that was portrayed in Town Hall from [Tea Party activists] John and Katy is something that I can relate to in a lot of ways.

Filmmaker: Such as?

Pettengill: For example, John speaks throughout the film against the welfare state, that it’s going to be the downfall of America. The idea of relying on the State is what will take this nation down from something great to something that is a complete failure. By the end of the film, he has to accept that he’s going to have to put his mother on Medicaid because he can’t afford her health care any other way. I find that really tragic rather than something to be mocked. Katy is striving for a life that’s bigger than she is. That could be seen as a wonderful and heroic impulse, and it’s important to think about the gap between what values we’re all trying to live up to and the actual reality of our lives. I became more aware of things like that by making this film.

Personally, I spend a lot of time thinking about money and class and what we are not supposed to talk about in terms of that. When it comes to presuming what your audience wants, there’s a tendency to gloss over those issues. It’s a really hard time to be in New York right now, and there’s this creative class that exists that does not come from money. That’s not really a conversation that’s been had. The sustainability of the industry is questionable since none of us are able to make a living off of our creative endeavors, but it’s also what’s at stake for different people depending on their backgrounds. Talking about this is, more or less, neglected. And that’s a gray area too since I’m not talking about extreme poverty. I didn’t grow up in a horrible situation, but I certainly was less privileged than most people I encounter in the art and film worlds these days.

For me, that was one of the most appealing things about the story of Cutie and the Boxer. It’s quite subjective, what poverty looks like. What do they deserve as artists? What have they earned? What does New York owe them? There was a lot of talk as that film was being constructed. In creating its final assembly, we wrestled with how to speak about their financial hardship in a way that is present, but not overblown. Who gets to make art, and what does a poor artist look like? Who succeeds, and on what basis? The class element in these conversations is missing. Making Town Hall threw a lot of that into relief for me. People’s inability to sympathize with Katy and John says a lot about a cultural gap that I think is also class-based.

Filmmaker: The political arena is this kind of weird alternate cinema that makes a lot of sense to me because that’s how my parents learned about what class they were inhabiting (a fairly low one) and what they could do to move into another socioeconomic level. Reagan’s “Morning in America” campaign galvanized people, whatever side of the fence you felt you were on. The EU at the moment is going through its own confused and confusing galvanization because the center is just not holding and people are nervous as hell. And ironically it’s the right-wingers that tend to stoke that anxiety better than anyone.

Pettengill: We’re grappling with all of that right now in how to present this Reagan film. I wonder about audiences that are not American and if there will be a sort of glee in the absurdity of the American dream as presented by Reagan. It’s extremely easy to watch this footage and laugh because a lot of it is really funny and bumbling. There are moments when he’s displaying incredible incompetence. He can’t give a speech without heavy notation. He’s really being scripted through everything. I think it confirms a lot of people’s worst ideas about the vacuity of politics, in general — this notion of American might, and the projection of the vision of ourselves to the rest of the world. That will be the most simplistic read.

But the crumbling of the façade and this nervousness you’re speaking about is a really interesting point because I’m pretty sure we will be tapping into this really dark place. It’s so obvious that the façade is crumbling. It becomes much less funny when one really begins to see what begins to happen in the ‘80s. History really repeats itself that way and the selling of that presentation is much less effective now. The attempts are still made, however, and that was what was so striking about the Tea Party. They’re really grasping onto the last vestiges of an America that never existed but they’re still trying the same techniques.

The Reagan film is told over eight years and you see this disintegration of an idea. It should prove to be a bit terrifying. We’ve been looking a lot at a film called The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu. It’s an amazing film and the stakes there are much higher in terms of what was happening in Romania and the façade crumbling. It’s a film we think about a lot, the way it portrays the gap between presentation and reality.

Filmmaker: Are you going to address Ronald Reagan’s early stages of Alzheimer’s? No one was talking about it during his presidency, of course, but in hindsight, we can surmise that there was something going on neurologically, perhaps.

Pettengill: That’s still the unanswered question about Reagan. If you read some accounts during his presidency, there is this common thread of people talking about the incompetence from the beginning, that he wasn’t ever really on top of it. No one has really been able to quite pinpoint when the Alzheimer’s started and its effects. His behavior during the Iran-Contra hearings seems as if he really has no idea what’s going on; he doesn’t remember anything. He doesn’t know what the question is. That could also just be a really wonderful performance in trying to escape responsibility. There’s a speech, his first public address where he confirms that Iran-Contra happened. He says his heart tells him that he didn’t do it, but the facts say otherwise. Alzheimer’s and performance and also maybe his own wishful thinking all point to the fact that he’s concerned with large ideas and less concerned with practical truths. All three of those things are hard to pull apart, and it’s a big knot in the film. It’s a central conceit of the film that in order to explain things away, we can’t just use one lens in which to look at this behavior.

Filmmaker: Let’s switch to producer talk. The complexity or the simplicity with which you’re going to approach these kinds of decisions must be at the heart of these conversations with your director. I feel unsettling audiences is important, and I feel the creative producer’s role in this kind of decision-making can be key. You did a program at UnionDocs a few months ago called Documentary Fundamentals where you talked about incorporating these kinds of conversations into the creative process. Since you both direct and produce, what do these roles mean to you?

Pettengill: Hopefully this might be changing, but the whole documentary world is geared toward simplicity, particularly in the funding structure. I’ve been writing an angry screed to myself over the past year against redemption narratives. Aside from funding, people don’t trust documentaries that aren’t activist in nature in some way or don’t have clear heroes and villains. The Overnighters, which I think is one of the most stunning films of the year, is having a hard time theatrically because people don’t know how to speak about it. It marinates in complexity. Ultimately, it’s a conservative impulse that’s hidden under very liberal language to try and show the individual triumphing over the system as an example of how personal agency can win the day. It’s really built into the American spirit.

I worked a bit on a film called Northern Light, an oblique portrait of families in the Upper Peninsula [in Michigan] living through the recession. It’s told through glimpses around corners and overheard snatches of conversation. It’s a frustrating film to describe. That film didn’t get any funding but was a critical darling upon its release. Zach was able to shoot all of Cutie and the Boxer without funding support. The cinematography is so gorgeous that when it came time to look for money, it was a bit easier than expected. But that film is a bit of an outlier in terms of getting institutional support because of its complex narrative. These are the projects I tend to be drawn to and in speaking about a creative producing role, the challenge is writing about them and figuring out how to speak about them in a way that communicates the urgency that these kinds of projects must see the light of day. I haven’t solved it.

Filmmaker: I was speaking to Deborah Stratman about this kind of literary impulse one needs to have in terms of getting support for “difficult” or opaque pieces of work, things that one cannot sum up in a short synopsis. She spoke about her aversion to having to name things before they’re formed in order for this kind of important institutional support. It relies upon using the right language – not to describe the work itself, but to describe its social impact or its causal reach to an audience.

Is working with archival also a mode of writing? Do you think this literary impulse is important in working with this kind of material?

Pettengill: For me, archival feels closer to painting. You can’t really rely on a piece of material to stand on its own for a long amount of time. You’re cutting around things that will lead the audience towards a different conclusion and what you want them to focus on. There’re often these small, almost still-like images, a few seconds that you’re capturing of a longer clip. Editing is a process of collecting images as well and carving out the more elementary elements of the image than you might do in a vérité film. It’s closer to art making than it is to how a documentary is structured, a different practice. That is, if it’s allowed to be. There are a lot of really badly made archival films. If it’s the sole source material, then it’s a very creative process.

Filmmaker: How does one inform the other? You were talking before of wanting to gain some distance from this stolid and reductive documentary tradition. Because I don’t think things will change in terms of the onus being on the maker to shepherd the film through its marketing and distribution channels. Filmmakers want it to change desperately but I have spoken to several makers who are asked by potential distributors what their complete outreach, festival and exhibition plans are, which is a bit confusing since the assumption is that that’s supposed to be their job. What kinds of conversations do you and Pacho have to help define your relationship after the film gets made?

Pettengill: Pacho said something really wonderful in the beginning of our conversations about working on this together. He said, all films consist of two or three people in a room making something. Defining these roles is more for these external factors you’re talking about, helping people make sense of what you’re doing, and it’s a constant conversation about what those roles look like. Producing Cutie and The Reagan Years are very different experiences. I came up using a PBS model where the producer of a documentary film was also the director. I don’t really know what they mean when these terms are used in this way of a director-producer team. The things that draw me into projects are the strength of the material and the complexity of the story being told. It’s also the person who’s making it and my desire to be in a room with that person figuring out how to best make the film. I’m organized and a good writer and those skills often help communicate the project to the outside world before it’s done. That’s the role I tend to take. Negotiating deals is a necessary evil but it’s not something I’m really good at. If I were good at that, I’d probably be in a different field altogether where I could actually make some money.

Filmmaker: It seems as if this kind of peer mentoring goes hand in hand with doing creative work, which by its definition, is very lonely. Not just mentoring, but also pushing one another to recognize what’s meaningful, what has value and why. That’s what I see much of, particularly in independent film and more specifically in documentary. It’s become more and more vital to everyone’s emotional survival.

Pettengill: Having been on the outside of certain circles for most of my career – I didn’t go to film school – and kind of wrestling my way into the community, there’s a real danger in painting a rosy picture of a group of talented people sitting around hugging one another and exchanging films. That said, some of that does exist. However, it’s also the antagonistic stance of certain colleagues that can be validating. Robert Greene is a very good friend and he’s also a critic. He really did not like Town Hall and he wrote something on it. I didn’t find much that was offensive about what he wrote, but he did refer to Katy as someone very hard to sympathize with and John as one of the most unlikable characters in recent memory. He and I went out for a drink and talked about it, a very frank conversation. I actually enjoy being pushed and called out. What makes me most nervous is to show films to my friends and not be sure if people are telling the truth. It’s a supportive environment but I also find the challenges thrown down to be as gratifying as anything else.

I really struggle with being in New York because it’s a really hard place to be making work now. At the moment, I’m working on four jobs at once and making The Reagan Years on the side. I’m also directing a short film in Afghanistan this summer and preparing for that. It’s a struggle to survive here.

Filmmaker: Why do you stay?

Pettengill: The people that are here – I can’t imagine re-creating this community somewhere else. I’m uncomfortable defining what others see in me but I also have a firm foot planted in the fine art world. I’m drawn to people who have the same interests as I do and we gravitate towards one another. I’m sure communities like this exist elsewhere but there are specific relationships and partnerships here; when I think about trying to duplicate that somewhere else, it’s really daunting. It’s not just finding the people who can reflect back your ideas to you in a useful way but I do feel like we’re all informing one another’s work. I’ve had really fascinating conversations regarding money and class with other friends that come from a similar kind of place or background that I do, and seeing that reflected in their work has informed my thinking and the kinds of films I want to make. I have this fantasy of finding an island off the coast of someplace scenic and being able to just buckle down and get to work, but a lot of that work comes from these conversations. I was at Yaddo last summer and I got a lot done there but the people I met there and the conversations we had were really important. Luckily, they also live in New York. Humans matter.

Filmmaker: You now have in front of you an opportunity to pitch a project that’s in process in front of a community of people that you don’t know. And they don’t know anything about you except for the representation of your work. There’s a lot of curiosity on the part of struggling European producers – who are not that used to such an independent model – about the independent American producer working today, particularly in documentary.

Pettengill: We’re dealing with our own set of preconceptions, which is that European documentary film is decoupled from the needs of activism and outreach and things like that.

Filmmaker: But what I’m beginning to see here is that they’re trying to imprint just this type of model you’ve been seeking to get away from. There is a movement on the part of festivals and other for-profit entities who realize that’s where the money is because traditional TV channel commissions are really becoming a rarity, budgets are shrinking and there is a distinct lack of being in touch with current trends in the marketplace. I know producers here are floundering and trying to learn a whole new way of talking about making nonfiction.

Pettengill: It’s true that the view is idealized on both sides and if what you say is true, I find that troubling. I think a lot of the American producers who are heading over to CPH, including myself, have this idea that this is a calm port in a storm of activist films and that’s a huge part of the appeal, getting to talk about nonfiction filmmaking as an art form rather than as documentary film.

Filmmaker: That’s true at CPH more than most festivals.

Pettengill: Not specific to CPH or the European context itself, but what I was saying earlier about the difficulty of talking about the descriptive language you need to talk about the complexities of a lot of these films, I find it’s another opportunity to try and do that. I’ve been watching a lot of narrative films that regard time and history in really strange ways. Films are anachronistic. I’ve been watching movies like The Long Goodbye, and Trouble in Mind. There’s a Western from the ‘60s called The Lonely Are the Brave that really plays with the traditional cowboy themes. These films really force you to reckon with history and the contrasts between then and now, how physical spaces can hold such a range of things that happened over time and try to capture them in these really bizarre, slippery, almost surreal ways. It doesn’t really help me speak about it, but I’ve been looking at those films for the cinematic language they’re using that encompass what is most appealing and difficult with working with archival footage.

Filmmaker: Archival, by its very nature, is referential. The way memory works, in each clip you see and what synapses fire when we see certain imagery, is an important impulse I think a lot of filmmakers don’t take advantage of enough. It’s the way we can curate for one another and share all the weird, offbeat knowledge we have – you should read this book; you should see this movie. It sparks off conversations we have about making something.

Pettengill: Yes, exactly. I mean these films I mentioned, which were all recommendations based on conversations I was having with people, are pretty far afield of what you might think of in the context of making a documentary. The further out on the fringes something might appear to be are sometimes where the most interesting connections can be made.