Back to selection

Back to selection

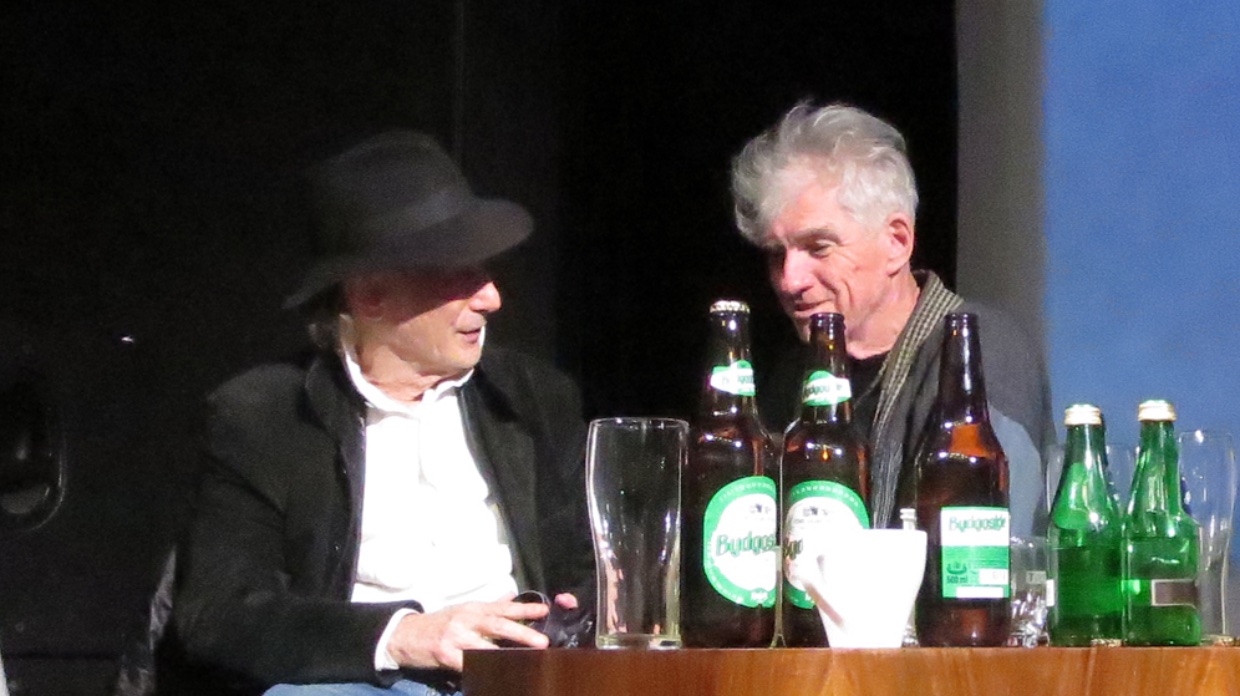

“It is One Film, Which is Called Your Life”: Christopher Doyle, with Jasper Spanning, at Camerimage

For several years Christopher Doyle has been a fixture at Camerimage, the annual festival in Bydgoszcz, Poland, devoted to cinematography. This past November he was especially busy, hosting two panels called “The Language of Cinema Is Images” with his friend and colleague Ed Lachman. Extending over six hours, these were a chance for Doyle, Lachman, and their guests to share stories, give advice, and question each other about style and technique.

The panels were also an opportunity for Doyle to screen some examples of his work. Leslie Cheung dancing to “Perfidia” in Wong Kar Wai’s Days of Being Wild. A daring helicopter shot over the Iguazu Falls from Happy Together. And footage from private, unreleased projects, including a day on Shanghai’s Suzhou River with Tilda Swinton.

Doyle spoke with Filmmaker on Camerimage’s closing night, where he presented Julien Temple with an award for “Outstanding Achievements in Music Videos.” Sitting in on the conversation was Jasper J. Spanning, director of photography for the Danish feature The Guilty. Later that night Gustav Moller would win the Director’s Debut competition for the movie.

Filmmaker: Can you talk a bit about the Tilda Swinton footage you screened last night?

Doyle: I do a lot of talks, it’s a way to focus ideas. The clips to me are just therapy, a collage. It’s a way of working through something. They’re not really films, they’re not really about filmmaking. They’re about, as much as possible, process. Or the idea of what intent we bring to what we do. It’s not what you do that matters, it’s why you’re doing it.

With Tilda, she was in Shanghai for some reason, and we spent six hours together, and this is the result.

She’s such a wonderful person, I’ve known her since she was nineteen years old. But we never actually worked together. This is the only time we did. The intent, her energy, they’re astonishing. She was 54 or 56, and she looks pretty good. Jasper’s not going to look like that when he’s 56.

We shot most of it with a lens baby. A lens baby is a hundred-dollar piece of shit. It’s just a piece of glass. You put it on the camera and it has this distortion, it blurs the edge of the frame. There’s only a little bit of area which is in focus, because it’s a piece of glass. It’s not a real lens.

So we got on a boat in Shanghai, the Suzhou River. We shot 80% of it on the boat. I’ve never seen anybody shoot from the river. Everyone shoots the river, but nobody shoots from the river. I could see this city which I know so well in a different way.

Filmmaker: How do you work with her? Did you direct her poses, her actions?

Basically what happened, we just did it. I didn’t have a script. People like Tilda, they’re so used to the camera that you don’t need to say anything actually. We had this wonderful time together.

Even in my stupid way, I know what the camera is going to do. I shot it, I so-called directed it. I think it was, “Let’s celebrate this time together.” Theoretically we were supposed to promote the clothes, it was for a couture house. So there are clothes, and all these people fussing around the clothes. But it wasn’t about the clothes. It’s about the energy of the two of us sharing an afternoon together.

With Tilda, there’s something that comes from my Asian-ness. It’s about the exchange of energy, it’s tai chi, it’s this give and take between this person in front of the camera and the audience through us, the DPs. I really believe, as I said in my panel, there are three people involved in a shot: the performer, the cinematographer, and the audience.

Our obligation and our grace and our astonishing pleasure is that we’re the person closest to the person who’s sharing with the audience. How do you get there? You have to be organized, number one. You have to be prepared. You have to have a certain authority, as I tried to say in the panel. Even when you have no idea what you’re doing, you have to pretend you know what you’re doing. And then you instill a certain amount of confidence and trust.

I just did a film in Japan where they said, I’ve never seen all this sexy, I’ve never seen a sex scene like this in a Japanese film. I said I know, because you think it’s about boom-boom. It’s not, it’s about movement, it’s about texture, it’s about how light hits your skin and all your other stuff.

Filmmaker: Tilda’s footage is so hypnotic, but will anybody get to see it? And how much footage like that do you have?

Doyle: Hundreds of clips. I try to make it different every time. Like I said, many people have said, even Alan Parker said it, you only have one film in you. And you’re always making it. I’ll be making this one film for the rest of my life. I think that’s important to realize — it is one film, which is called your life. You celebrate it in different ways. You go to the beach on the weekends, you go camping, in the winter you like to ski.

I think this is part of what Camerimage is about. It’s a celebration, not just of a movie, but of life. It’s not you or me being superstars, or not being superstars. The great thing about Camerimage is that we’re all together. The kids actually think that they can do it. Whereas the film school tells them, “You have to pay $28,000 for the next semester.”

Why isn’t Jasper saying anything?

Filmmaker: The film he shot, The Guilty, was Denmark’s selection for Best Foreign Picture. He had to solve a difficult problem because it’s basically a one-character film in a tightly confined space. How do you keep that fresh for 85 minutes? You run out of shots very quickly.

Doyle: This is a good question. I also write a lot. When I work with young filmmakers, usually we write the script together now. Always I say, “Where is the camera?” Then you have this interesting discussion. They say the scene is two people talking. And I say fine, but it’s a movie. Where is the camera? What are the angles? So few filmmakers think that way. So, it’s two people in a car. Fine. Why? Why don’t we just stop the car, somebody wants to take a pee, and then we can have the conversation outside the car.

Spanning: Why? That’s the question. When I read the script for The Guilty, it was all in real time. So there are no scenes, or rather it’s just one long scene. It’s just one guy, and he’s on the phone at a call center, an alarm dispatch center. So all he does is speak on the phone.

All the other characters, all the action, happens on the other end of the line. It’s very much a character study. It was such a great pleasure to go into the total basics of photography and filmmaking and finding out how the smallest details have great impact. What does a focal length do? What does proximity do? All these tiny things that we would have to use the right way to tell the story — they were profound when you actually go into them.

Filmmaker: What happens when you take everything out of the frame, and you’re left with just his face? Plus you start out bright and end up in a dark little room. You have to express his psychological progression in purely visual terms.

Spanning: Well that whole progress starts with the script, that’s where the visual style of the film is. If it’s not written visually, you can only do so much. In my case I was able to go to the script and say, let’s have him turn off the light here. So the character would do the lighting changes. We can do that visual progression from bright to dark, but it would come from the character shutting the blinds or smashing up a work station so it got completely dark.

But all that should take place on a script level.

Doyle: I don’t know about you, but I try to get involved even when the filmmakers don’t have the money for the film. I’m trying to get involved in locations as early as possible. So then it’s not just somebody writing a script in a room. Once we have the space, or an idea like you say like turning off the lights, once you include that into the script, the whole thing works much better. Because otherwise you’re on set and it’s moribund, it’s dead. I think as a cinematographer, the earlier we get involved in the script, the better the film will be.

Filmmaker: But then there are times when you don’t have a script.

Doyle: [Laughing] Wong Kar Wai never had a script.

Listen, how many good Shakespearean films have you seen? Most people say, maybe three to five. Over the last hundred years of cinema. He wrote them four hundred years ago. So the script is not the point.

Think about it. His plays are pretty good. So how come they’re only five good Shakespearean films? Maybe because we as cinematographers are not involved in the evolution of the script.

I work with so many first-time directors who are not thinking about the angles. If we’re just sitting in the corner of this room here, the three of us, we’re fucked. But if we put you here, and Jasper’s sitting at the piano, and we open the door — ahh, we have five more angles. Whether we use them or not is another thing.

Sometimes the job is boom, boom, boom. That works best for certain things. But sometimes you need a certain elegance, a certain sense of space. You move from the piano over here and have a drink of water. The earlier we get involved with that as cinematographers, the better.

Because many directors and writers especially are not super-visual people. They’re thinking about ideas. But we can give that idea a form, the light, the composition it deserves. And the earlier we get involved with that, instead of just coming on set and trying to work it out then, the better the film will be.

Spanning: Something I did actually learn in film school, we were getting feedback on a story about a pregnant girl, and the question was why did you show her pregnant belly? And that resonated with me in terms of, don’t just shoot what’s in the script. If it’s written properly in the script, it will come across. As a cinematographer, you need to find what’s under the surface and film that. Find the darkness in the character instead of trying to film “It’s dark.”

Filmmaker: Chris, can you talk about how you transform a location when you shoot it?

Doyle: Last night I’m sitting there looking in the audience and I see a girl who has her hair dyed. Or look at those three different buttons over there. Every bloody minute of every day is a journey. I know mathematicians and musicians have a similar world. I’m sure people who like wine or food, it’s an astonishing thing. Once you focus, it becomes part of who you are.

This corner over here, how horrible this little halo of light is. All the time, we’re living with this all the time. It’s such a gift. I didn’t plan it. I never went to film school. Somebody gave me a camera and I’m here now. I don’t know why.

I’m a sailor. I grew up by the sea. I think it informs me.

Filmmaker: You capture something in the people you shoot. That heartbreaking clip you showed of Leslie Cheung. When you watch him in other movies, he’s a playboy or a crook, a performer. But in your clip he was a real person.

Doyle: I did ten movies with Leslie. With Leslie, it was like, I’m this close with the camera and he would ask, “How was it, Chris?” I’m not the director, you know, so I’d say great, and then the director would say whatever. But he really needed assurance. He’d be into something, he was so engaged, we were engaged together. To me it was beautiful. It was this give and take, this engagement, this trust, this moment shared.

Same with Anthony. Leslie and Anthony Bourdain were the two most beautiful people I’ve ever known. [Doyle shot an episode of Bourdain’s Parts Unknown series.] We never met each other before we worked together. Then he came to Hong Kong and we clicked. But he gave too much. You give so much that you’re exhausted. I think he was empty, because he was giving so much to so many other people.

Leslie, he jumped out of a window April 1, 15 years ago. He didn’t want to get old.

Filmmaker: Tell us about starting out in Taiwan. You were friends with Edward Yang and Sylvia Chang?

Doyle: I went to Hong Kong to study Chinese and then I ran out of money. At that time Taiwan was cheaper to live. I’m hanging out there, I run into people like Hou Hsiao-hsien, Stan Lai, who’s now one of the greatest theater directors in the world, etc., etc.

I met people, and then somebody gave me a camera. I made all these mistakes and I started to do this stuff. And then Edward Yang comes back from the States, he wants to change the world. Sylvia was his girlfriend at the time. She happened to be related to the head of a government-financed company making movies.

Edward wanted me to shoot his first feature film. But this motion picture company had 26 cinematographers on salary. And I’ve never shot a film, I’ve never even held a 35mm camera before. I have no idea about lighting. Really. I had only done 16mm documentaries.

He tried to hire me, and the whole company went on strike, because first of all I’m not even Chinese. You have 26 people to choose from, why choose me? And Sylvia stood by us. If it wasn’t for Sylvia I wouldn’t be here now. Really. Sylvia said, “Chris is going to do it.” They worked out a compromise: somebody on staff got co-cinematographer credit. He came by every other day, “How are things? I’m going fishing, bye-bye.”

Sylvia was the actress. And it’s called That Day, On the Beach. It was kind of a seminal film, one of the first so-called women’s films in Taiwan. It was the #Metoo film of that period.

Spanning: That’s your first film?

Doyle: That was my first film, and it’s all because of Sylvia. It’s an extraordinarily generous thing that she did. I had never even touched a 35mm camera before. I had no idea how to light, I had never lit anything before.

Now I’ve got to go get ready for Julien Temple.