Back to selection

Back to selection

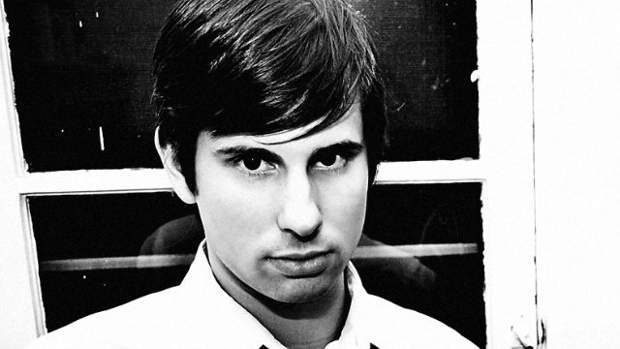

Five Questions with Joshua Tree, 1951: A Portrait of James Dean Writer/Director Matthew Mishory

What began as a short film, Joshua Tree 1951: A Portrait of James Dean, became a feature film almost by the insistence of social media. Director/writer Matthew Mishory says the initial shoot for the film took place in Joshua Tree, California, over a few days in 2010. When he returned to Los Angeles, he edited a trailer and posted it online, not thinking much of what would happen. Almost immediately the trailer went viral and expectation was that it was going to be a feature film. “Our production team got together and decided, well, we really ought to be making the next feature film on James Dean because the world already thinks we are,” he says.

So with the leverage from the trailer’s online attention and from the footage already shot, Mishory managed to get a feature funded. The result is an evocative, nuanced, visually stunning black and white intimate portrait of a period of time in the life of James Dean before he was a household name.

Starring James Preston, Dan Glenn, Dalilah Rain, and Edward Singletary, Jr., the film is making its way around the world on the film festival circuit, having runs at Seattle, Transylvania, Rio, Flanders, Reykjavik, and screening this week at the Palm Springs International Film Festival. The film received the Jury Prize Winner at the 2012 Image+Nation Montreal Film Festival.

Mishory talks about how he approached making a film about such an iconic character, and the reasons behind some of his production choices.

Filmmaker: Did you know from the beginning of this project that you wanted to focus on a year in James Dean’s life before he was a well known actor, or was that decision the outcome of your research?

Mishory: What I found most interesting, and why we focused on 1950 to 1951, is it’s the period before anyone had really heard of him. What surprised me was how little time he spent as a celebrity. The majority of his short young life was a struggle. It was that year that was formative for him. I thought that was so much more compelling and interesting than the 6-12 months in which he was very successful. We wanted to focus on a period that was less commonly portrayed in previous films.

Filmmaker: Why did you choose to shoot the film in black and white and how did you convey your atmospheric vision to your cinematographer? There are silent moments in the film that evoke some of the strongest emotions.

Mishory: To me, it was always going to be a black and white film, although there are brief flashes of color that represent subjectivity and memories. I just never saw it in any other terms.

I was very lucky to work with such a great cinematographer, Michael Marius Pessah, who happens to be one of my close friends. We didn’t want to just recreate the look of a film from 1951, that would have been too boring and too much like pastiche. We looked at the films of Douglas Sirk, like The Tarnished Angels, as a starting point. We looked at Ansel Adams photography and also film studio stills of the day. So we started with the look of a film from the 50s and then added modern elements, and elements more particular to my sensibility, techniques in film that would have never been used in the early 50s, such as macro lens shots. I also like to use zooms, so there are a couple of very long slow zooms in the film that you would never have seen in a 50s film and maybe not even today.

I’m glad you mentioned silences because I think the film can be challenging for some because it’s not a two-hour gabfest that’s constantly full of action. For me that’s really where characters reside — in those silent moments. Dean, especially, was someone who spent a lot time living inside his own head. That’s a challenge as a filmmaker, to portray that in a movie. It made sense to work in a slightly different way. And I think having an actor like James Preston who can convey so much by saying so little was a good marriage.

Filmmaker: You’ve described the sexual images in the film as “omni-sexuality.” How have audiences responded to the sexuality in the film?

Mishory: Generally we’ve been really pleased by the audience response to the sexuality. At the European premiere, at the Transylvania International Film Festival, the film was probably more controversial for its form than for its content. We’ve had screenings in smaller cities in the Midwest where there has been a more polarized audience response to the content but my job is just to make a film and put out into the world. It’s for audiences to respond. My own personal feeling is that something that is common knowledge can hardly be controversial, so to me the film and its content are entirely non-controversial.

Filmmaker: There are a few moments in the film when James Preston looks very much like James Dean, but for the most part, he exuded Dean more than physically looked like him. Did you decide to purposely avoid the cliché James Dean look?

Mishory: It was very intentional. We wanted there to be a few moments where he definitely looked like a young James Dean just so people got the general idea about the movie they were watching. But for the most part, we wanted to step away from that.

We don’t have him in thick glasses and we don’t have him wearing a pompadour constantly. I felt the signature James Dean look was probably not really a look that the real James Dean probably wore all the time, or very often. People think they know who James Dean was, but their basis for that assertion is a T-shirt they saw in a souvenir shop or a coffee mug or photographs that Dean himself staged. We weren’t making the film to necessarily sell the image of James Dean.

Instead of creating a very strong physical resemblance, we wanted to create a very convincing portrait of who he might have been emotionally and philosophically. James Preston was the perfect actor for this because there was an interesting sort of synergy between his own life and the character. He was just a 19-year-old kid when he dropped out of art school in Texas and got in his truck and drove to Los Angeles to be an actor. He had many of the same struggles and difficulties swimming with sharks and wading his way through the Hollywood industry like James Dean so he understood who this guy was.

Filmmaker: The film is shot mainly in two locations: Los Angeles and Joshua Tree. Did James Dean spend time a lot of time in Joshua Tree? Why did you choose that desert site as one of your locations?

Mishory: The idea of James Dean in the desert was gleaned from a little-known, and I thought interesting, fact that he spent time in the desert during a period later than we portray in our film, but I moved it forward a few years. When he was discovered on stage by Elia Kazan and brought back to California to star in East of Eden, he had spent a cold winter in New York. He was very pale, so the studios sent him out to the desert with his roommate to tan. When I read that during our research, I thought wouldn’t it be great to be able to make a James Dean film that’s not set in New York, and not even entirely set in Hollywood either, but set in the desert, which to me is one of the great locations and also historically where artists have gone for decades to be inspired.

People often ask which parts of the film are factual and which parts are more fictionalized and it’s usually the opposite of what people think, so the sequences in the city are almost entirely taken from the history and recollections of the people who knew him. The sequences in the desert become a symbolic and an emotional landscape.

The isolation and mood of Joshua Tree becomes almost a character in the film. That’s why the film opens and closes there. Technically we did some things to make that happen, we used certain color filters even though we were shooting in black and white, and of course we shot film, because to me this was a movie that always needed to be shot on film. I don’t generally like to work on video, but this especially was a film that needed to be shot on 35mm.