Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions With The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz Director Brian Knappenberger

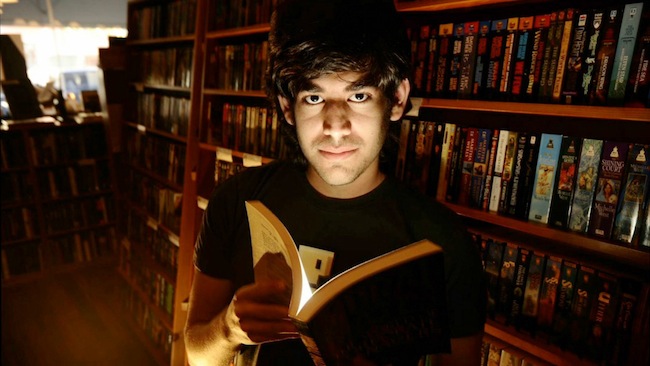

The Internet's Own Boy

The Internet's Own Boy In a time of endlessly self-spawning bio-docs about the rich and prominent, Brian Knappenberger’s The Internet’s Own Boy carries a legitimate current-day charge. The film is both a dogged investigation in the tradition of Errol Morris or Josh Fox, and a hugely emotional oral history of Swartz’s life — which ended when the activist committed suicide in January 2013. Swartz was facing a federal investigation after he downloaded a cache of academic journals (including, but by no means limited to, JSTOR) from the main computer network at MIT, with a possible penalty of up to 35 years in prison.

Indicted under a computer fraud law that was enacted by Congress the same year he was born, Swartz’s legal battle eventually overran his life, but not before the astonishing success of a web petitioning campaign he headed up to prevent Congress from passing SOPA in 2011. The Internet’s Own Boy is thorough history detailing the charges and the ethical implications of Swartz’s trajectory, but also a cautionary tale not to disassociate Internet use with legal freedoms. More than one participant refers to the pressure on Swartz as example-making. The Internet’s Own Boy premiered at Sundance and screens today in the Festival Favorites section at SXSW.

[Ed. note: With a bonus sixth question.]

Filmmaker: You have an incredible roster of interviewees, including people who were very close to Aaron, and you’ve indicated that the full interviews will be made publicly available for fair use later in the year. Were people as forthcoming for the documentary as they appear?

Brian Knappenberger: It’s an interesting story because we have people in the field, like Cory Doctorow and Laurence Lessig, people who are trying to just deal with this loss. A kind of personal, individual loss. And they’re trying to struggle with the question, “Why?” “Why did it happen?” You know, what were the factors that went into it, and what does that mean – you know, because the story had these kind of bigger contexts. In a sort of bigger-picture sense, his story said a lot about modern life. People opened up to me. I had three or four conversations with his father, and the rest of his family, they opened up to me. I think it’s amazing that they did. I think good films are made from moments of trust, and courage. It took courage for them to open up to me and I’m grateful, because I think we really learned a lot about him.

Filmmaker: Do you see his same activist streak being taken up today by the people who knew him?

Knappenberger: I think it was first a set of technological issues for him, and he as a person moved in a more political direction. But it was certainly not first or second or third priority for him starting out. It’s remarkable how young he was — you see him at twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fighting for a kind of open, free-culture movement across the web. People are inspired by Aaron; he was somebody who turned his back on the traditional startup culture. Where you kinda create something, sell it to a big company, turn around and do it again; he did that with Reddit and then moved on into this kind of political consciousness, where he decided his time, energy and his prodigious skills were best served in the pursuit of really, genuinely making the world a kind of place. Not as a generic startup slogan – really and truly seeing what’s wrong with the world, and asking, how do you quantify your role in changing it? So I think the people who feel frustrated by the system, for example a legislative branch that’s entirely useless, they’ve responded to Aaron’s story because he was using new technological means and actually having that effect.

Filmmaker: For interviews, did you seek out anybody on the institutional side? MIT, the Department of Justice?

Knappenberger: Yeah. Both. The biggest issue I regret on the film is, the government didn’t wanna say a word about Aaron’s case. They were relatively nice about it and it was a lot of effort, but they were never gonna say anything about the case: what they were thinking, what kind of charges they would have brought, what the arguments would have been. Just the speculation we pieced together from what the lawyers told us, you saw in the film — but it never went to trial. We don’t actually know what the case would have been like. So, we did some speculating on that with the caveat we’re speculating. I wish they would have talked to us. I’d take it seriously. But they definitely declined. So that definitely was an area where we shut out.

They did a kind of dance with us — they said we should get the MIT Report. We got the MIT Report. The guy, Hal Abelson, said he would do an interview with me when it was done, and then when it was done he backed out. He said, “I don’t wanna do it.” MIT didn’t have this kind of dance. Some people at MIT feel passionately about Aaron’s story, feel like the administration did wrong. And the administration hasn’t said a lot about it other than the MIT Report; I think they’re just hoping it goes away.

Filmmaker: If so, how did you get access to their security camera footage of Aaron downloading the archives?

Knappenberger: That was from the legal discovery, from the evidence collected against Aaron by the prosecution. That’s how we were able to get it.

Filmmaker: The Internet’s Own Boy sort of proposes two different paths of entrepreneurship, and you delineate how Aaron took the less-lauded one. We praise Mark Zuckerbergs, but whistleblowers and open-source innovators are usually disdained as “hackers” — you wanted to explore that juxtaposition in the film?

Knappenberger: I was very conscious about that, and I hope that it’s coming across in talks and Q&As. I wanted to make this point: the internet is not a distant realm of geeks and hackers and IT people. It’s the place in which we all live. Every single part of our lives has an online component to it. And, we get a say in how it exists and as a machine we need to look into its laws. I don’t think you need to be a startup or a huge company; it’s an area in which you have creative expression, discussion, protest. I want to communicate that for sure, both in the film and talking about it at festivals.

Filmmaker: Discussing Aaron’s story at festivals, do you meet people who had never heard of him?

Knappenberger: We do. It sparks a lot of interest and a lot of people find resonance in various parts of it. Even from the early work that he did, the fact that he was a child prodigy. People really respond to somebody who is that rigorously trying to use all their skills in order to disrupt a system that seems broken, and to really make a difference.