Back to selection

Back to selection

5 Questions for Raising Bertie Director Margaret Byrne

Raising Bertie

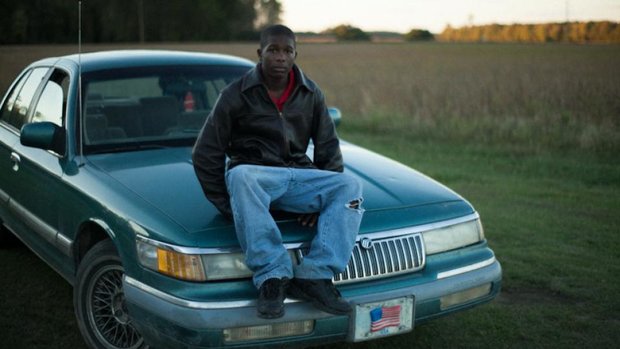

Raising Bertie Raising Bertie follows three young men over the course of five years as they grow into adulthood in Bertie County, a rural African-American-led community in North Carolina.

Director Margaret Byrne had originally set out to make a short film about The Hive, an alternative school for at-risk students. But when the school was shut down due to lack of funding, she saw the potential for a broader project about the underfunded rural educational system and how it affects African American boys, in particular.

Shot in intimate verité style, the film follows Reginald “Junior” Askew, David “Bud” Perry, and Davonte “Dada” Harrell through disappointments, heartbreak and triumphs. Through their stories, we see the complex issues facing America’s rural African American youth.

Byrne worked as an editor and DP on the award-winning American Promise, another longitudinal documentary which followed African American boys over a period of years in the educational system.

A single mom based in Brooklyn, Byrne brought her daughter with her while she was filming. Though Byrne self-financed the project for years, she eventually received funding from various sources including the MacArthur Foundation, Ford Foundation and the Southern Documentary Fund. Co-produced by Kartemquin films, the award-winning Chicago filmmaking collective, Raising Bertie will have its world premiere at Full Frame Documentary Film Festival on April 9.

A single mom based in Brooklyn, Byrne brought her daughter with her while she was filming. Though Byrne self-financed the project for years, she eventually received funding from various sources including the MacArthur Foundation, Ford Foundation and the Southern Documentary Fund. Co-produced by Kartemquin films, the award-winning Chicago filmmaking collective, Raising Bertie will have its world premiere at Full Frame Documentary Film Festival on April 9.

Below, Byrne answers five questions about how she identified her subjects, how she collaborated with her editor, and her social impact goals.

Filmmaker: Finding the right subjects is crucial for the success of any documentary, but especially for a longitudinal documentary like Raising Bertie. How did you find the three main characters? Did you start following more subjects initially and whittle it down to these three or were they always the focus?

Margaret Byrne: When we started making the film in 2009 we filmed four young men from The Hive [an alternative school for at-risk youth]. From those initial shoots, we decided to work with Bud and Junior. They had very different personalities and ambitions and we connected with them quickly. I saw promise in them despite their struggles. I knew I wanted to find a third character. About nine months into production, I met Esther Harrell, Dada’s mom. We had been following the local board of education races and she was outside handing out flyers on voting day. She told me about her son that attended The Hive and we decided to visit them on our next trip. When we met Dada, I was struck by his emotional honesty. I’ll never forget that first interview because he was so open and so sad about the recent separation of his parents. At that point I knew I found the three families we would follow.

Filmmaker: I know you worked on American Promise, which also followed the education of African-American boys over a long period of time. How did your experience working on that film influence your approach to Raising Bertie?

Byrne: Working on American Promise exposed me to the art of longitudinal filmmaking and the importance of building relationships with your subjects. While American Promise follows two middle class African American boys and their experience at an elite Manhattan school, Raising Bertie examines the lives of young men attending a struggling rural high school. I saw all that Bertie had to offer and I knew that this was a story that needed to be told, especially because there was little national media on the state of rural education.

Filmmaker: Was it challenging to convince the community — and specifically, the three main families — to let you film such intimate moments? Did bringing your daughter along with you help to break down barriers?

Byrne: I think one key to making an intimate film is having a small crew; it was just Jon and myself. Jon Stuyvesant, DP and Producer, is a close friend and a long time creative partner. We both committed to making regular trips and staying involved in the guys’ lives.

We didn’t have any resources, but we were determined to make the movie and tell their stories and I think they respected us for that. We were always consistent. There was never a time we stopped coming, so they knew they could trust us. Bringing my daughter along made it more of a family affair. Often one of the moms would watch Violet while we were filming and sometimes I would watch their kids, so we helped each other. I’m grateful for the time we spent together.

Filmmaker: You filmed over six years. How much footage did you capture along the way? And how did you work with your editor to cut it down to feature length?

Byrne: We shot about 400 hours of footage over the course of six-years. Everything was logged and we had transcripts of all the interviews which was extremely helpful. Leslie Simmer, our editor, and I went through all the footage and decided on key verite scenes to work on. We made a list of scenes and we started building the film from there. We edited for close to two years. We felt it was important to take our time in the edit and consider carefully how we told the story. We also had several feedback screenings.

Filmmaker: What were your goals for the film when you were starting out and what are the impact goals for the film now that it’s done?

Byrne: When we started this project I was focused on understanding the complexities of the young men and the community itself. About a year ago we started crafting our impact campaign. Ian Kibbe is our Impact Producer, as well as the Producer of the film. We held an engagement summit in Durham in late March which was hosted by The Self Help Credit Union. We brought together community leaders, stakeholders and issue experts to help determine the most strategic way to elevate the public conscious and create a national dialogue around the systemic issues that restrain the achievement of young people like those represented in the film. That is my hope.