Back to selection

Back to selection

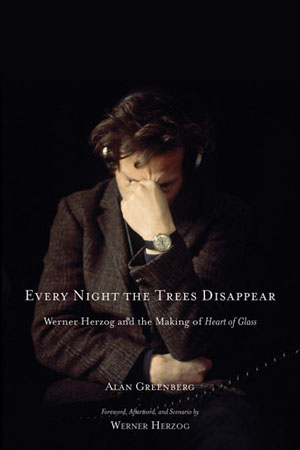

Werner Herzog and the Making of Heart of Glass

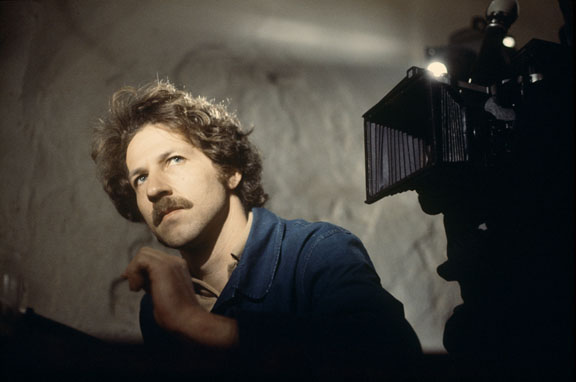

In 1976 Werner Herzog hypnotized his cast of actors and directed one of the strangest narrative films in the history of cinema, Heart of Glass. Alan Greenberg, then a young writer, aspiring filmmaker, and Herzog disciple, was on the set, and thirty-odd years later he, and Herzog, would like to tell you all about it. Hence, Every Night the Trees Disappear: Werner Herzog and the Making of “Heart of Glass” (Chicago Review Press).

Greenberg had fallen under Herzog’s spell the year before, when he was sent by a film journal to interview the director. Neither cared for that process, but the two discovered they shared the same ideas about film, music, and athletics. During this meeting Herzog mentioned an upcoming film project that involved hypnosis. The relationship was solidified when Herzog told Greenberg, “You must join with me. There is work to be done, and we will do it well. On the outside we’ll look like gangsters, while on the inside we’ll wear the gowns of priests.”

Herzog has repeatedly asserted that the hypnosis was not about controlling his actors. Before shooting he told Greenberg, “This will be done for reasons of stylization and not for reasons of total manipulation. …this use of hypnosis could give us access to our inner state of mind, starting from a new perspective.” The stylization he hoped to achieve would fit the film’s theme, collective madness.

The plot is simple and beside the point: in a Bavarian village in the late 18th century, a glassmaker dies and takes to his grave the secret of his ruby glass. The glass factory owner goes mad trying to unearth the formula. As he goes, so too goes the village.

But this is not a madness of the stark-raving variety, this madness is more subdued, more subtle. The hypnotized actors, and many of them were nonactors, seem stilted and somnambulistic; they move as if weighed down and underwater. When the actors interact their glazed eyes look at points far off into some unknowable distance. Everyone’s timing, in speech and action, is off, everyone is disconnected from their surroundings. Only Hias (Josef Bierbichler), a Nostradamus-like visionary who foresees the town’s demise, has focus. Bierbichler was the only cast member not hypnotized, and his performance is remarkable considering he’s acting with and reacting to, essentially, a bunch of zombies.

Half of Every Night the Trees Disappear is an early draft of Herzog’s script, and in it you can detect what he was after. At the glass factory: “The men become mute, the Paralysis overcoming them, as they grow into marble and ore.” At the village tavern: “… people sit down, madness etched upon their faces.” Of the factory owner: “All this time, something like restless despair emanates from the factory owner.” Herzog wrote the stylized movements and expressions he was hoping to capture and these descriptions gives us a hint of what he may have suggested to his entranced actors.

Greenberg was present for at least a few of the hypnosis sessions led by the director, and these he recounts vividly.

“In two minutes, all four farmers were deeply hypnotized. Recognizing this, Herzog gave them their acting directions. He told them that they stood on heavenly ground, but when they opened their eyes they would see a land troubled by terrible Giants. They would be so frightened, he went on, that their lips would twitter and their limbs would shake. But he assured them that no matter how fearsome things might seem, they would be quite safe and well protected and could speak their lines with no trouble whatsoever.”

To hypnotize someone in two minutes seems exceptional, but why quibble. It is the result that matters. From the first scene that features human faces–those farmers–we know something is askew, that this film is about to take us to a place Robert Bresson could only dream of.

Greenberg spends a fair amount of ink on material that has already been covered on the Heart of Glass DVD extras, in the interview book Herzog on Herzog, edited by Paul Cronin, and in Burden of Dreams, Les Blank’s film about the making of Fitzcarraldo, which shows a film set that is controlled chaos. But what’s new here is the fuller picture of the cast and crew that orbit Herzog during a production. These people, none of whom are named Klaus Kinski, seem to promote a sense of chaos, a chaos Herzog embraces. (One of Herzog’s many proclamations in the book is “Chance is the lifeblood of cinema.”) A consultant on the film, Claude Chiarini, who was a gunner with the French Foreign Legion before he became a neurologist at a Parisian mental institution, notes, “Herzog’s coordinate points are strange. They have a psychotic character, although he is not by any means psychotic. He surrounds himself with madness. The people he knows and works with are primarily mad. Ultimately that is not very good for him, I think.”

Greenberg spends a fair amount of ink on material that has already been covered on the Heart of Glass DVD extras, in the interview book Herzog on Herzog, edited by Paul Cronin, and in Burden of Dreams, Les Blank’s film about the making of Fitzcarraldo, which shows a film set that is controlled chaos. But what’s new here is the fuller picture of the cast and crew that orbit Herzog during a production. These people, none of whom are named Klaus Kinski, seem to promote a sense of chaos, a chaos Herzog embraces. (One of Herzog’s many proclamations in the book is “Chance is the lifeblood of cinema.”) A consultant on the film, Claude Chiarini, who was a gunner with the French Foreign Legion before he became a neurologist at a Parisian mental institution, notes, “Herzog’s coordinate points are strange. They have a psychotic character, although he is not by any means psychotic. He surrounds himself with madness. The people he knows and works with are primarily mad. Ultimately that is not very good for him, I think.”

In addition to the mad, he surrounds himself, like many directors, with people who will follow him to great lengths. Such as Regina Krejci, credited as the script girl.

“Regina had met Herzog in Vienna just two months earlier. After a retrospective screening of his films there, Regina knew for sure what she must devote her life to. She begged Herzog for a position on his production team. He was taken by the intensity of her plea.

‘Walk from Vienna to Munich,’ he said, somewhat seriously. ‘That will tell me how much you want the job.’”

She does.

And Greenberg does a fine job of relating the risks he took for the sake of “a few essential shots.” To capture the mysterious ending, Greenberg convinced some fishermen to sail treacherous seas in bad weather to Skellig Rock, an island off the coast of nowhere.

If Herzog seeks to capture the inner being of a person, he also seeks to capture the inner being of a landscape. No doubt the remoteness and desolation of Skellig Rock appeals to Herzog, but it’s not a stretch to think he was hoping some of its history would bleed onto celluloid, a history that saw ascetic monks being thrown off its cliffs by marauding Vikings around 1,000 C.E.

Greenberg also dispenses more Herzog yarns. The stories that surround the director are mind boggling: rescuing Joaquin Phoenix from a car wreck, pulling a boat over a mountain, getting shot by a drive-by shooter while being interviewed, surviving Klaus Kinski. Greenberg tells tales of swimming under the ice of a frozen river, conversing for minutes while standing on his head, hitting a tree with a snowball 70 feet away on his first attempt, and resurrecting a roadkill lamb! This is all entertaining stuff and perhaps might best be considered examples of “ecstatic truth,” a phrase coined by Herzog in his “Minnesota Declaration” to represent a truth that does not rely on facts, numbers, charts, actual quotes, or cinéma vérité, a truth that “can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

Every Night the Trees Disappear is not a “how to make a film” book by any means (John Sayles’ Thinking in Pictures: The Making of the Movie “Matewan” is the best of that genre). It’s not even a “how to make a Werner Herzog film,” because the hypnotism sets Heart of Glass apart from the rest of his films, and everyone else’s films for that matter. The book is a portrait of an iconoclastic filmmaker at work and provides some insight into the process that led him to include shots of albino alligators at the end of Cave of Forgotten Dreams and other such mysteries. For the Herzog completist, it would do well standing between Herzog on Herzog and Kinski Uncut. Somewhere in there lies some kind of truth, ecstatic or otherwise.