Back to selection

Back to selection

Grass Roots Marketing, Speaking Fees for Filmmakers, Publicity Tips and the Release of I Am Not Your Negro at DOC NYC’s Marketing Bootcamp

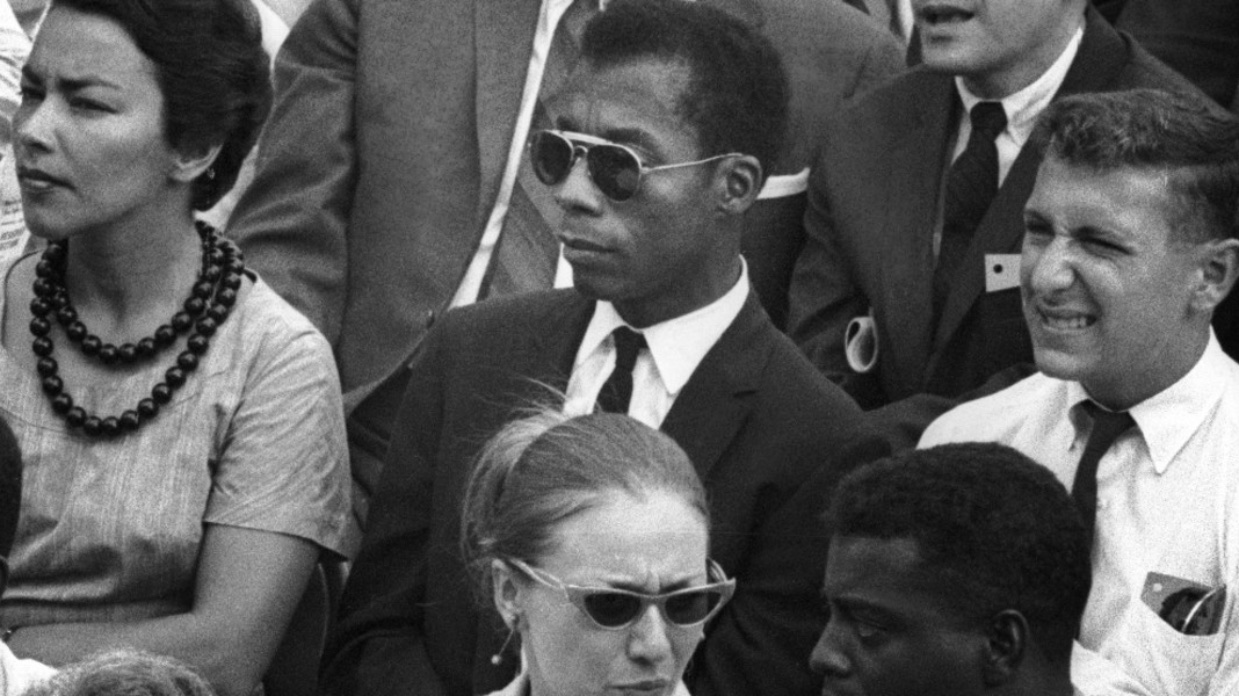

I Am Not Your Negro

I Am Not Your Negro This is the third and final part of coverage of DOC NYC’s Marketing Boot Camp. (Read parts one and two here at the links.)

Christie Marchese of Picture Motion, a marketing and advocacy firm for issue-driven films (Leonardo DiCaprio’s Before the Flood, Ava DuVernay’s 13TH, and Michael Moore’s Where to Invade Next), gave a presentation on developing social action and grassroots marketing campaigns.

She made the point that grassroots marketing and impact campaigns are two different things: grassroots marketing targets audiences who are pre-disposed to be interested in your film. Impact campaigns are geared toward those who aren’t organically interested. One of the key services Picture Motion provides during a film’s social action campaign is bringing on partners to help expand and engage each potential audience segment.

When building partnerships, they seek to:

• Execute the social action campaign.

• Identify shared goals and create new initiatives to meet campaign goals.

• Secure commitments to promote viewership on TV, in theaters and at film festivals.

• Promote theatrical screenings in areas where their constituency is active.

• Host influencer and word-of-mouth screenings.

• Facilitate post-screening conversations and events.

• Drive group sales for theatrical distribution.

• Garner press attention and spread awareness.

With so much ground still to cover in this incredibly informative event, and because it is often the film’s distributor who brings these guys on, I’m going to move on to the next presentation, a conversation between publicist Susan Norget and Thom Powers, DOC NYC’s Artistic Director.

According to Norget, filmmakers sometimes ask her to help get their film into festivals, but she cautioned that no publicist can do that for you. What she (like any other advocate, be they fellow filmmakers, sales agents, etc.) may be able to do, depending on the relationships at hand, is bring your film to the attention of programmers who have thousands of screeners to get through.

No one at these events ever wants to answer fee or budget questions, and Norget was no exception. After much back and forth, Powers was finally able to get her to confirm a $5,000 – $25,000 price range for a publicity campaign. They joked that she’d never actually take on a film for five grand, but she said she’d done it for one film for which she was only targeting a very specific segment of the press — the Jewish press, in that case. (A note for filmmakers: as someone who has hired many publicists and also helps out other filmmakers with publicity, it is certainly possible to find publicists who work at a variety of rates, so make sure you shop around and get referrals!)

Norget usually works on a film for several months. (Although she didn’t specify this, it’s reasonable to start looking to bring on publicity as long as four months prior to the film’s launch, especially if you’re going after national press. Otherwise, at a minimum, you want to give at least two months lead time with all materials in hand. Materials include a synopsis, trailer, electronic press kit, promo clips, bios, a list of prestigious festivals and awards, stills and posters.) An earlier start gives a publicist like Norget more time to work on the press kit, messaging, developing materials, and to pitch journalists sooner.

Norget also noted that documentary filmmakers, by dint of living with their projects for so long, and from working on grant applications, holding friend & family screenings, etc., have generally honed in on a lot of the messaging already. So when she comes onto a project, it’s about fine-tuning — working with the filmmaker on angles and framing while also bringing a fresh set of eyes to the project. That could mean helping a filmmaker choose the best images, crafting messaging around the great music, or just finding the elements that really stand out and making sure those are prominent in their materials.

On communication expectations between filmmaker and publicist, Norget says a good rule is to establish in advance what those expectations actually are. She usually sends a status update once a week once the film is being pitched or screened, as well as attendance reports and reactions from press screenings.

Powers noted that there’s less space in many outlets for film reviews now than there was just a few years ago. The New York Times, for instance, used to review any film that was released for a one-week theatrical run in New York. That’s no longer the case, and things are changing even further with the addition of Netflix and Amazon to the premiere space. Norget agreed, and added that getting press often depends on whether the film’s subject matter is deemed to tap into the political or cultural zeitgeist.

A successful publicity campaign involves a fair bit of strategy and timing. For a festival premiere, you want the trades (Variety, The Hollywood Reporter) but you probably don’t want a New York Times feature, because you want to save that for your release. Although Norget did note that these days, that policy is a little more case-by-case, because the Times is reviewing fewer films. She said that in some circumstances, it might be a case of “take what you can get,” but generally publicists are not courting reviews in mainstream publications for festival premieres, and definitely not when there’s a distributor in place.

Aside from reviews, there are opportunities for features, interviews and curtain-raisers (“The Ten Must-See Films at Festival X”). Norget gave the example of a film she has at Tribeca this year. Anticipating that it will get a release, and because it’s not the type of film people might expect it to be given its subject, she’s thinking about the kinds of feature stories that will help frame it in the way the filmmakers want. The idea is to help establish its profile, so people coming to it later, when it’s released, have that information already tucked away. By and large though, she said, “You want to save the good stuff for later, when [the film] reaches a broader public.”

She added: “If a journalist gets in touch because they maybe see the Kickstarter, you don’t necessarily want them writing about it when they hear about it, but perhaps closer to release.” Powers suggested that filmmakers also keep track of the people and outlets writing about your film’s subject throughout its production. In my own experience, whether you’re working on publicity yourself, with a freelancer or with a major publicity firm, those contacts that you yourself personally make often turn out to be invaluable.

Turning toward filmmaker sustainability, the next talk was “Earning Income From Lectures,” by Lacey Schwartz, director of Little White Lie, a film about growing up white in a Jewish family only to find out when she was 18 that her father was black.

When Schwartz finished the film in 2014, she had all kinds of goals around it. She wanted people to see the film, to make money, to build her name as a filmmaker and to position the film as a go-to on the issue of identity and family secrets. She also had goals around personal enjoyment, but she had to balance all of this with her family life and other responsibilities. Becoming a paid speaker was a way of furthering all these goals.

In fact, that started happening while she was still in pre-production. When she started doing research for fundraising, she connected with a lot of people in the Jewish community, and they started asking her to do some consulting: not just around the film, but also around the issue of identity. She ended up getting a lot of consulting work in the Jewish community around racial and ethnic diversity.

She then started doing paid speaking engagements in the community using her trailer. She made some money, but she was also strategic about not showing too much of her film early on — not over-exposing it and thereby undercutting distribution or festival opportunities.

Because she had ITVS funding and knew the film would be on PBS, leaving only a small window before broadcast to get it out theatrically, she figured out that she would focus on quantity of festivals over quality. She simply tried to bring the film to any festival with any audience that her film spoke to, and she was able to brand the project as very diverse to a lot of communities. Schwartz handled the press herself, first targeting Jewish press to put together tear sheets and to prove that there was interest.

Because she’d been saving all her press contacts, including someone from the New York Times who had reached out to her a few years earlier, once the film was finished she was able to go back to them. She landed the cover of the Fashion and Style Section, which put the film in exactly the context she wanted. Without hiring a speaking agent, universities, state departments, and other organizations contacted her, and she started to travel with her film, doing paid talks and Q and A’s after her film, as well as giving presentations about how to tell your stories.

Although she didn’t divulge typical speaking fees, Schwartz suggested having someone else do the negotiating around rates. She also worked with Picture Motion on outreach for a while, and they helped her professionalize her rate structure. On another project, they did handle the booking for them and offered her as a speaker.

I caught up with Schwartz afterward at the happy hour reception, where, with a $4.00 wine in hand, I asked her a few follow-up questions. At the peak of her run, she booked about 10 engagements per month, including festivals. She said some festivals will also pay an honorarium for speakers and according to Schwartz, sometimes even for doing a Q & A. (I’ve been paid screening fees, but never Q & A fees, so that was news to me. The point, I suppose, is that everything’s negotiable.) Three years out, she now books roughly two engagements a month. Summer’s slower, and she’ll see an uptick during things like Black History Month.

And that brings us to the last presentation of the day: a case study on the marketing of Oscar-nominee I Am Not Your Negro, a film directed Raoul Peck, based on James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript about the history of racism in America, Remember This House. This took the form of a conversation between Thom Powers and Director of New York Publicity at Magnolia Pictures, George Nicholis.

I Am Not Your Negro had an unusual release and marketing journey. It premiered at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival, where it was acquired by Magnolia Pictures on the strength of the film itself and reaction to screenings. They bought it before too many reviews came out, and quickly made the decision to qualify it for Oscar consideration, which required a week-long theatrical run in New York and Los Angeles).

The film only did a few festivals — Toronto, New York Film Festival, and DocNYC — and then went straight into its December 9th Oscar-qualifying run. This generated a lot of press, including many positive reviews. Magnolia then released the film on February 3rd, at which point it got more press, including a New York Times review.

According to Nicholis, Magnolia usually works with a N.Y. and L.A. publicity agency, with the New York also handling long-lead/national press, but on this film they had a N.Y. publicist handling newspapers and radio, an L.A. team for the L.A. theatrical, a digital agency for clip placement and online sites, a regional publicist, an African-American outreach agency, a faith-based agency, plus an awards consultant/publicist… and they all had to be coordinated. Magnolia also hired outside social media agencies, and they reached out to influencers early on to get word of mouth growing.

Powers asked whether the time spent going after celebrities was worth it. Nicholis noted that they sometimes rely on the agencies (William Morris, CAA, etc.) who represent celebrities to ask them to sneak these potential influencers a DVD. Samuel L. Jackson, who narrated the film, also took part in the PR push. Magnolia also hired an impact agency and set up screenings for NBA teams who had a free night before a game with nothing to do (apparently, this is a thing). Said Nicholis, “So it’s the cost of a screening room. It really helped the word get out.”

If all of this sounds expensive, it was (on an indie scale, at least). While Nicholis couldn’t confirm an exact amount, Powers asked if it was — ballpark — over six figures, and Nicholis didn’t shoot that estimate down. He also said that was more than they usually spend on P & A (prints and advertising). During the Q & A, I asked whether the P & A budget had been a deal point from the filmmaker during the acquisition negotiations. Indeed, it was, but he said the budget was also an evolving thing as more partners — namely Amazon — came on.

And while a six-figures spend is a lot of money, it’s tiny in Hollywood terms. Nicholis said also that free social media was a really valuable part of their campaign. Magnolia has a Twitter page and handle, and they create a specific one for the film they’re working on. For a film like this, with so much content and favorable press notices to share, they retweeted and engaged with the journalists. Said Nicholis, “Sometimes other people would see it and want to run a piece as well.” They also put advertising money into Facebook and Instagram ads.

Does social media have any role in acquisitions? Yes, Magnolia checks for reactions at festivals. Nicholis explained, “We used to stand outside the theater and get exit reviews from audience members. It was awkward…. Now people are tweeting before they’ve even seen the film. So we track Twitter and Facebook — mostly Twitter — and the [publicity] agencies will routinely circulate the Twitter reactions like they would a Variety review.”

Powers asked which press outlets were the ones Magnolia absolutely wanted to get for the film. These made the list: NPR, Morning Edition, Weekend Edition, Fresh Air with Terry Gross, New York Times, LA Times, Wall Street Journal, Associated Press. Powers noted that podcasts have taken up a lot of that space, with Marc Maron as solid as a Fresh Air get. Nicholis agreed, and added Two Dope Queens out of WNYC. Powers also added Mic.com and Buzzfeed to the list of current big gets in a constantly changing landscape.

And remember, if you’re planning to do the publicity full court press, national publications like Vanity Fair and Vogue have long lead times, generally requiring four months of planning.

All in all, the day had been packed with information and good advice, and I was ready for the happy hour drink specials around the corner where many of the participants and audience gathered. Not as many filmmakers showed up as I would have expected. So my last word of advice to those who attend these things is to heed something Morgan Spurlock said back at the start of the day: “This is a business based on relationships.” Next time, if you can, try to go to the after-party, even if you don’t know anyone. You’ll be surrounded by people who, like you, care about movies and are pushing their own boulders up mountains, so there’s bound to be something to talk about. Or maybe even a connection to be made.

Audrey Ewell is the director/producer of two widely distributed documentary features, and has also worked as a director/producer in narrative. In addition to bringing on traditional PR for festival and/or distribution on her films, she (previously) spearheaded digital marketing and (currently) runs traditional publicity campaigns on her own and others’ films.