Back to selection

Back to selection

A New Kind of Magic: Douglas Trumbull on Magi, HFR and Dynamic Frame Rates

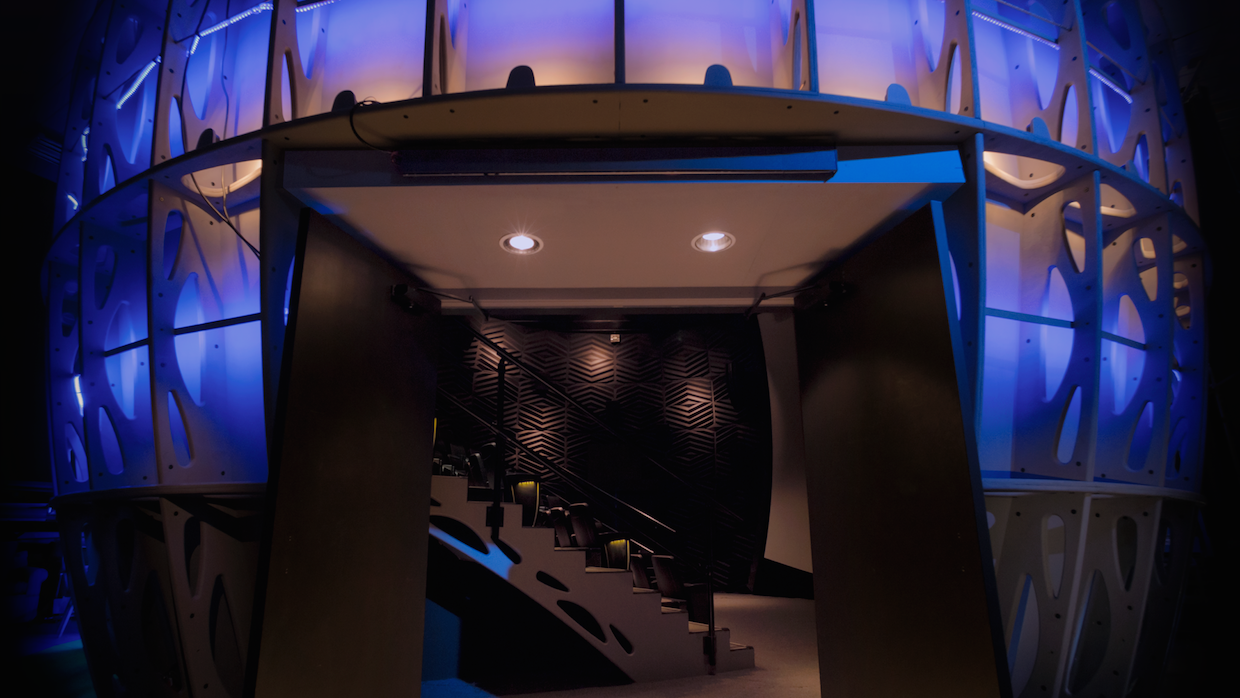

The exterior of the Magi pod (Photo courtesy of Douglas Trumbull)

The exterior of the Magi pod (Photo courtesy of Douglas Trumbull) With the passing of Douglas Trumbull, the great visual effects pioneer, we’re reposting Sam May’s 2017 article from Filmmaker’s Summer, 2017 print edition on his innovative late-career work on high-frame-rate cinema. –Editor

You might not recognize the name Douglas Trumbull, but you will certainly recognize his work. He is the man behind the special effects of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and also the director of Silent Running and Brainstorm. In recent years, he has dedicated himself to “figuring out the future of cinema.” The result: Magi cinema, a means of shooting and projecting films in 4K 3-D at 120 frames-per-second (fps).

In the beginning films were shot at around 16 fps before becoming standardized at 24fps, which has remained unchanged since. Many aspects of film production have been experimented with and improved, but frame rate has remained the same for a simple reason: More frames equals more film, which equals more money. But the advent of digital has now made increasing the frame rate as simple as the flick of a switch, yet examples of HFR (high frame rate) films remain few and far between.

Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit trilogy was captured at 48fps, the biggest example of a mainstream experimentation with frame rate, but it was not well received, with many complaining of a “video” look to the film. “The problem with 48fps is that it is too similar to television,” Trumbull explains. “In the U.S. that standard is 60fps and in the U.K. it’s 50fps. It’s almost identical, so audiences associate 48fps with television. When you go beyond to 120fps or even 144fps, which all standard projectors are capable of, it becomes something else entirely.” More recently, Ang Lee’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk was shot at 120fps in 4K 3-D. Lee met with Trumbull about his system, but the two directors’ approaches are different, despite their matching specs — a distinction that has passed many by, myself included. This has not stopped Magi from becoming embroiled in the lackluster response to Billy Lynn. The film was subject to many of the same criticisms aimed at the Hobbit trilogy, with the even higher frame rate polarizing many.

Magi is a patented system that solves the problems associated with 3-D projection, such as motion blur and eye strain, and aims to move away from the “video” look associated with digital by creating a film-like image. Incorporated through both the shooting and projection of a film, Magi has several attributes that aim to improve the viewing experience. Standard 3-D shooting using two cameras capturing images in sync, but they are not then projected in sequence; frames will be flashed several times, making it hard to register motion. Magi captures the left- and right-eye frames alternately, 60 frames per eye, so when projected they will be seen in the order that they were shot, removing blurring and strobing. “All standard digital projectors run at 144fps,” Trumbull says. “When films are projected at 24fps, frames are flashed four to five times, so the film is effectively stopping and starting 24 times a second, but you don’t consciously register it. What Magi in 3-D does is projects frames in the order they were shot with no repetition in what I call perfect temporal continuity.”

Digital cameras and projectors do not have shutters like their film counterparts; the lack of the flicker effect created by a rotating shutter leads to a “video” look more associated with television. Magi recreates the flicker effect of a film shutter through the alternate capturing of frames, so that when projected through a single projector, the alternation between left-eye and right-eye images replicates the shutter effect of classic film projection. “The flicker effect is something audiences unconsciously associate with a film experience,” Trumbull says. “Television doesn’t have that flicker effect, so when the flicker is removed, audiences begin to associate the images with television.” Doing so overcomes the darkness that hampers 3-D projection. “By capturing 100 percent of the action by shooting the left and right eye out of sequence,” Trumbull explains, “50 percent of the light goes to the left eye and 50 percent to the right, so the projector’s brightness is being used 100 percent of the time.”

Magi also has the ability to dynamically change the frame rate throughout projection, so differing scenes can be shot at 24, 120 and 1600fps and be presented together in situ. (It’s also 2-D compatible; says Trumbull, “I just prefer 3-D.”) Trumbull has learned from failed technical innovation of the past, including his own, Showscan (70mm 60fps), by making Magi affordable and compatible with standard digital cameras, all standard digital projectors and DCP (Digital Cinema Package) distribution systems. It is also distributable through Magi “pods,” prefabricated cinemas engineered to create the best results from Magi at a reduced per-seat cost.

After becoming disenfranchised with the industry after the production and release of Brainstorm, Trumbull relocated to the Berkshires in rural Massachusetts, serving as his home and studio, which houses the Magi cinema or “pod.” The exterior is reminiscent of a UFO, or rather the cinematic representation of a UFO as a glowing, pulsating spheroid-like construction. Inside is an intimate space for viewing, with 70 seats; while that may not be a huge number, each seat has been optimized for the greatest viewing experience, meaning there are no bad seats. The screen itself is not only curved horizontally but vertically as well, allowing it to reflect as much light as possible and create the best possible viewing angle wherever you may be sitting. Its reflection is also aided by actually being silver rather than white.

The pod is optimized to enhance both the viewing and aural experience. Thirty-two separate speakers are strategically placed around the auditorium, enhanced by dual rotary subwoofers under the seating capable of creating frequencies of 20 hertz and below and around 30 channels of sound for an experience much like the short-lived Sensurround that accompanied films like Earthquake in the ’70s. One of Trumbull’s future projects is to focus on benevolent aliens who communicate via telekinesis, whose voices will be modulated to be heard through everyday sounds.

Trumbull has a few pieces to show. First is UFOTOG, a short film about a UFO photographer caught up in a federal investigation — a vehicle to exhibit the attributes of Magi. During the film the screen seems to disappear entirely. The 3-D is exquisite; the problems many complain about during standard 24fps screenings — motion blur, eyestrain, darkness — all disappear. The representation of depth is wholly realistic foreground, mid and background objects appear tangible and connected to one another, rather than just cutouts. You feel like you could reach and touch anything. Despite being completely studio based, its use of green screen to create exteriors is seamless. The higher frame rate adds a gloss to everything onscreen making it feel that much more alive; the result is a living, breathing kind of experience. You also wouldn’t guess that it had been shot on Canon EOS cine cameras, a fairly cheap alternative to your ARRI and Red cameras.

The second short Trumbull showed was a CGI test featuring Chappie-esque robots where everything onscreen appeared to be real but had actually been computer generated. The results were strikingly lifelike, and again the standard 3-D problems were nowhere to be seen. Magi clearly not only offers improved results for live action but also for CGI and digitally created landscapes. There is also footage of two live studio performances; these showed of Magi’s potential in other areas of entertainment such as live theater. There are a few technical problems here and there, but what is clear about each clip is that they are all studio based; Magi has not been road tested, so to speak. Studio shooting is only one part of making a film — seeing how Magi copes with exteriors and daylight will be a big test to see whether it can handle the challenges of a feature-length film. Trumbull informs me that he will shortly be testing Magi on a Formula 1 shoot, which aims to push the technology’s limits.

Alongside the Magi pod Trumbull currently has a full-scale production stage under construction, which he will use to shoot his own planned features. Unsurprisingly, science fiction will be the subject. One of the problems Trumbull has with spacecraft-set features is the lack of windows; portholes may be the safest solution, but they limit visual results. His plans hope to go further than what films like Interstellar could achieve in fairly confined environs.

Trumbull’s location has not helped Magi’s development, he admits. Being so far away from L.A. has severely limited the number of people willing to come out to view his work. He is currently in negotiations to set up a screening facility in L.A.

After viewing what 120fps 4K 3-D has to offer, I sat down with Trumbull to talk all things Magi, Billy Lynn and the current state of the industry.

So where does the name Magi come from, and what is it? Magic without the c — Magi, the wise men. I wanted something with four letters, like IMAX. IMAX sells most of its tickets through brand recognition; it has the [most] brand recognition of any of these kind of things by far — that’s how it makes most of its money.

Magi aims to create a more immersive experience. Do you think this is the most important aspect to cinema going? If you look at the industry, it’s moving more and more towards immersive experiences. Take VR, for example; the problem with that is people don’t want to wear the headset. Immersion is what TV can’t offer; when 3-D took off, everybody started making 3-D TVs but now nobody is making them anymore. I think the problem with that was miniaturization. When you watch a 3-D image on the big screen, you have a 6-foot figure standing in front of you, whereas when you put that on a TV screen you have like a 6-inch figure. When I took the stuff we’ve been working on here and put it on my television screen to see what it looked like, the effect was completely lost.

Why is the brightness of the image so key? Is it a technical reason, or is it more to do with the audience and what they are used to? Fourteen-foot lamberts has been the standard level of brightness since the beginning. If you make the image any brighter, the flicker becomes apparent. The thing with television is that it was designed to be viewed in an illuminated space, unlike a film; your television or laptop screen is closer to 50-foot lamberts. You can put a film on a television screen and audiences don’t mind, but when you put a TV show on a film screen, audiences don’t like it — it has that “video” look.

Magi can be accommodated by most standard projectors, so cinemas won’t be required to install a new system. Can it still create the desired effect on a standard screen? What we have done with the Magi pod is optimise the viewing angle rather than number of seats. The perfect viewing angle is about 90 degrees, so in the pod there are no bad seats. The problems with Imax screens is that while you have plenty of seats high up, at the optimal viewing level, you get left with so many bad seats down at the bottom, when you’re stuck right at the front in the corner you can hardly make out what’s going on. I would never try to sell a seat like that.

Most older auditoriums are much longer than they are wide, generally at a ratio of 3 to 1. They weren’t designed for 3-D. This is what causes some of the problems with 3-D; when you’re further away from the screen, it’s harder for your eyes to focus on the 3-D effects. In the Magi pod you are the right distance from the action to stop eyestrain.

Magi can reduce some of the downfalls associated with 3-D, such as motion blur and eye strain, but it still requires glasses. Is glasses-free 3-D something you have ever looked into, or think could be viable in the future? I don’t know. Jim Cameron has been looking into that, but the problem at the moment is you can only achieve it with a very small angle of view; you have to be directly in line with it. But with Magi we haven’t had any complaints about the glasses; people say that when the films start the glasses seem to disappear.

The Magi pods offer a cheap, prefabricated method of exhibition, but how difficult would it be to refurbish existing theatres that do not have the space to accommodate said pods? The Magi pod, or podplex as I like to call it, is to create cinemas at a fraction of the cost, or even in existing theaters. You can put them in the back, in the lobby, in the car park. [The Magi pod] may not have as many seats but it offers the greatest return per seat, and, in terms of volumetric space, it’s also more profitable. Most cinemas now are ripping their seats out to put in big recliners and tables so they can serve food; that’s how they are making their money now, off the food and drink rather than the tickets. Multiplexes were designed to accommodate staggered screenings, to get people to the candy counter. When cinemas were just one screen, the candy counter would only get used before the screening, but now with multiple screens they can be used all the time. In China they are building cinemas daily because the medium is still new to them; the interest is still there. We’re going to do some things in China that are going to surprise a lot of people.

The industry is much more risk-averse than it used to be. Not many will take a financial leap of faith anymore. Has that affected Magi in any way? It’s not that they don’t want to take risks anymore; I don’t think people understand things. The number of producers I’ve talked to who don’t know what aspect ratio is, or what an optical printer is, it’s scary.

Magi will obviously create more data than shooting at 24fps. Will this be a financial burden? Shooting more frames per second might not have huge financial effects on the shooting budget, but how will it affect VFX? More frames means more time in the editing suite. Surely creating effects for 120 frames is going to be more expensive? Yes and no. When you have your effects shots created for 24fps you have to add blur to them otherwise they look like a cartoon, so this loses all the man-hours that go into it. When you render out finished effect shots with the added blur it just looks like crap.

You have also developed a means of using dynamic frame rates. Is this part of Magi? Do you think this will be a better way of combining action and dialogue scenes? Yes, that dynamic frame rate route means you can have your action scenes, your car chases and so forth at 120fps or even higher, and have your talking scenes at 24 or 48fps. I thought this was something Billy Lynn would have benefitted from. I would have shot just the flashback sequences at 120fps. The crazy thing is, you can even have two different frame rates in one shot; you could have your big monster or whatever at 120fps and the rest at 24fps. That’s unheard of.

How did your meetings with Ang Lee come about? In making Life of Pi Ang had became frustrated with the limits of 24fps working in 3-D. We had a mutual friend in Dennis Muren, who had worked with me on Close Encounters and went on to be a big deal at ILM. He had worked with Ang on Hulk. Basically, he brought us together as Lee wanted to shoot some HFR tests for a boxing movie he was planning that never materialized. When he became attached to Billy Lynn, he came to view Magi six times with various members of the crew and fell in love with it, but he wanted to go further with it, something he called “the whole shebang.” He decided to shoot with two cameras capturing 120fps for both eyes in sequence and project it with dual Christie projectors at 28-foot lamberts, which was just not possible. There were not screens big enough available to do this. This led to very vivid images, but they looked like video.

Was Lee aware of the rules you set for Magi? Why did he decide to not utilize these? Yes, he was aware. I don’t think he understood it. I tried to tell him and the producers several times that their methods wouldn’t work, but they were unresponsive to my emails, I begged Lee to come screen some dailies here so he could see what the problems were but I never got any response.

So on the surface, Magi — 120fps 4K 3-D, Billy Lynn — 120fps 4K 3-D. Do you think the lack of information about how they are different has damaged your efforts? Oh, definitely. The bad press around Billy Lynn hasn’t given HFR a good name; it has certainly pushed back our efforts of what we are trying to do here. Lee had arranged to screen some battle footage from the flashback scenes at the NAB convention. I was overcome. I mean, I was shaking. It took me about 30 minutes to get a hold of myself afterwards, and I thought, “this is really going to be something.” But it didn’t work out. When I went to the premiere at Loews Theatre in New York, it just wasn’t a good experience.

Magi can reduce motion blur and maximize action, but how does it handle the human face? I admit there will be some actors and actresses that won’t want to see themselves like that because you can see everything. There’s a long history of close-ups being softened — I’ve done it myself. There are ways around that though; you can use the dynamic frame rate if you don’t want to see your face up there in such detail.

Shooting in 4K 3-D at 120fps obviously creates a huge amount of detail resulting in very distinct images; do you think this visual style can suit any film? Many films’ artistic choices, such as anamorphic lenses, focus less on detail and more on creating atmosphere. Can Magi incorporate any filmmaker’s needs? No. I love standard 24fps 35mm. It can create beautiful images. We’re not trying to impose this onto every type of film. Magi creates a whole new kind of experience that is different and that has its place. All films will use a number of different lenses — wide angle for landscapes, long lenses for close-ups, etc. — but they are only projected using one lens. This means that you are constantly having to refocus, which is particularly troublesome in 3-D. What I do is shoot with the same focal length that the film will be projected in so it removes this effect.

Film formats like IMAX can create unmatched imagery but will never become mainstream due to financial drawbacks. Do you think digital could ever match film’s visual results? Yes, that’s what we’re doing here. This goes beyond anything we’ve seen before. Some people think that higher resolution and dynamic range will create better images, but the frame rate is the key to creating better images.

Some digital formats can technically create better images than film. Do you think the industry should be focusing on this? Are images that are technically superior better images? Some still cling to film. Is this because of nostalgia, or do film images have a more resonant effect? No, it’s not just nostalgia. Even an old 35mm print from the ’40s is of a better quality than a standard 2K digital DCP, but digital is here now and we have to embrace it.

Were Magi to find commercial success, would you contemplate going back into directing? That’s the goal. After Brainstorm, I never wanted to make another movie in the conventional way at 24fps. I could never do that again now; it would bore me. That has been the goal with Magi, to get back to a point where I can direct, and I’ve got to do it soon, I don’t know how long I’ve got left! We’re finally at a point where things can move forward, and I’ve got several projects that I hope will be happening very soon.