Back to selection

Back to selection

“Technology Has Come A Long Way”: Todd Douglas Miller And E. Chai Vasarhelyi On Going Big With Apollo 11 And Free Solo At IFP Week 2019

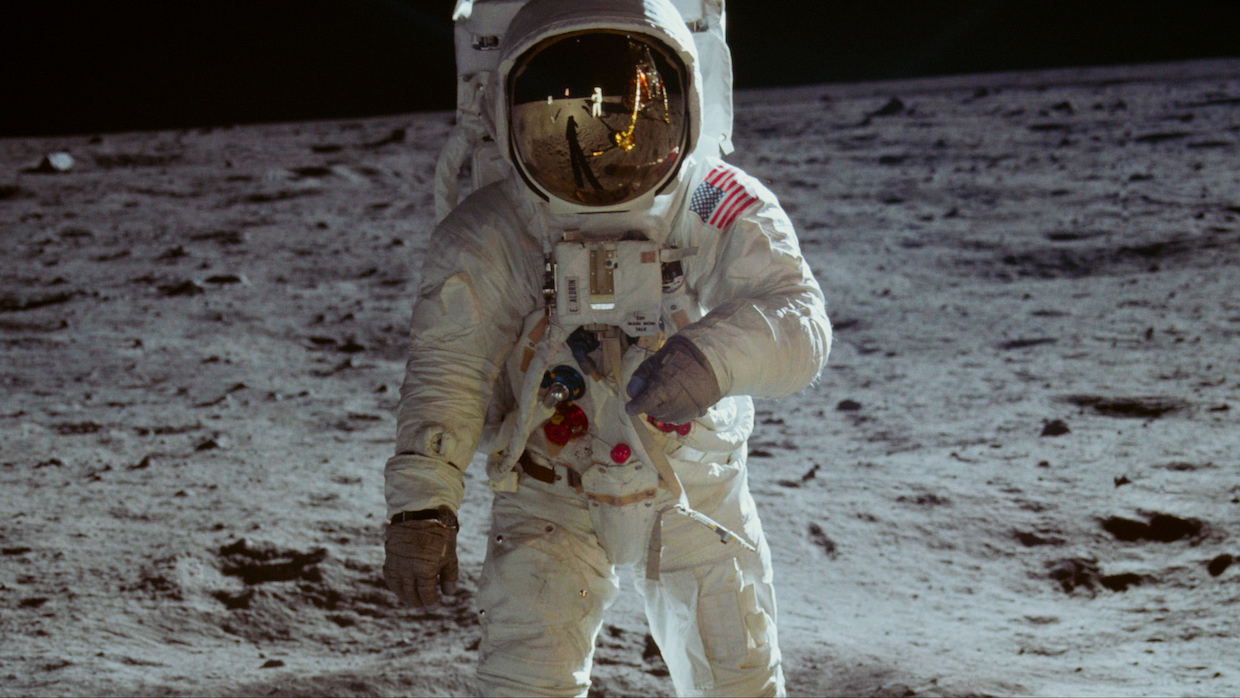

Apollo 11 (courtesy of Neon/CNN Films)

Apollo 11 (courtesy of Neon/CNN Films) Documentaries have been making bank at the box office the last couple years, which is heartening for anyone worried the blockbusters are the only game in town. Still, you don’t necessarily have to see small, intimate fare like Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, RBG and Three Identical Strangers on a giant screen. You can’t say the same about Free Solo and Apollo 11. One finds cutting-edge cameras hanging alongside mountain climber Alex Honnold; the other unearths 65mm footage of the eponymous spaceflight. Both played IMAX theaters, and they were an even better fit on the world’s biggest screens than the latest Marvel extravaganza.

Two of the creators behind these twin achievements came to IFP Week 2019 for a “Tête-à-Tête” chat: E. Chai Vasarhelyi, who directed Free Solo with her husband Jimmy Chin (not present), and Todd Douglas Miller, who helmed Apollo 11. Though they were both making large-scale non-fiction, their films, and their approaches, couldn’t be more different. Where Miller was working entirely with archival footage, Vasarhelyi and Chin used advanced cameras to create incredible images that wouldn’t have been possible even a few years back.

This is to say technology has finally made it easier to film mountain climbing up close. That doesn’t mean it’s easy: A good mountain climbing cinematographer has to be an expert in both mountain climbing and cinematography. That describes Chin, who filmed much of their previous film, 2015’s Meru, which chronicled Chin and colleagues’ attempts to scale the much-feared Himalayan peak.

“He’s also a National Geographic photographer, so he has a natural talent for documenting high-angle situations, which are incredibly extreme,” Vasarhelyi said. It’s not easy to make clean, non-wobbly images when you’re dangling on a peak, flirting with death. “It’s all about how long you can hold your breath and keep it steady. Because you’re at high altitudes you’re panting most of the time.”

Free Solo wasn’t as trying. For one, Chin wasn’t one of the subjects, and they had a small army of mountain climbing cinematographers who were able to rig their cameras before the big day. For another the mountain was El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, thus offering a more welcoming climate than the snow-capped Himalayas. “You just walk up to El Cap. It’s the most beautiful place on Earth,” said Vasarhelyi. “Meru is five days just to get there. You could never go back for a shot. That was the joke: ‘Go back, Jimmy!’”

Vasarhelyi said she and Chin sought to transform a genre. “Certain kinds of outdoor films aren’t so interested in the story. It’s like porn: You’re looking for the big action — that’s why you’re watching,” she explained. “With Meru and Free Solo, we wanted to take a big story and see if we could transcend the subject.”

Of course, there are ethical considerations. Honnold and Chin go way back, but Vasarhelyi had never met him prior. During their first solo hang, she suggested they make a movie about his climbing. “He said, ‘If you’re going to make a film about me then there’s only one film to make: If I free solo El Cap,’” she recalled. When she told Chin about it, he freaked out. “He told me we can’t make that movie, it’s totally irresponsible, because of the stakes.”

They deliberated over it, for fear that Honnold may perish on the infamous vertical rock, as many had prior. When they relented, they took extra caution: They didn’t tell the press, and they kept his climb a secret, even from locals. “Everyone at Yosemite knew something was up, but they didn’t want to add pressure to the situation,” Vasarhelyi said. It worked: On the day of, Honnold was relaxed. “As he climbed it was sublime: He was doing something beautiful and he was happy.”

By contrast, Apollo 11 was a breeze. It was just a ton of work: For one thing, gobs of footage had to be paired with 11,000 hours of audio. And yet by the time Miller was working on it, the Dinosaur 13 director already cut his teeth on space docs: He had just completed the short doc The Last Steps, about the Apollo 17 mission, when he was pitched on doing one for Apollo 11, whose 50th anniversary was then three years off. He was reluctant, hoping to work on his next feature, not looking to get sucked down another research hole. But once he learned about all the lovingly preserved, never-seen archival footage sitting in various national archive vaults, he couldn’t help himself, especially considering he could add to an event that’s already a part of the collective memory.

“It’s probably the most documented thing that’s happened historically in the last 50 years,” Miller said of the mission. Once he took a good look at the resources he’d have at his fingertips, he realized he was attempting something no one had before: To take all the footage and piece it into a single feature-length narrative. “The last major effort to translate anything of substance [out of the Apollo 11 footage] was back in 2007. And technology had come a long way.”

Perhaps Miller’s boldest decision was not taking a typical expository documentary route. “I wanted to do something that was closer to a direct cinema experience,” he said. No fan of talking heads, he stuck to creating a sensory, you-are-there experience, as though giant 65mm Todd-AO cameras were mere flies on the wall. That meant nixing any materials that weren’t part of the event itself. Miller speaks about the surreal feeling of being offered home movies and rare pictures from surviving Apollo 11 astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, as well as the late Neil Armstrong’s family. “They had things that have never been released publicly. It was very difficult to say, ‘I think we want to stick to our guns with what the creative is for this scene.’”

Miller also consulted Collins’ seminal book Carrying the Flame: An Astronaut’s Journey. “He talks a lot about things that happened on that mission that have never been depicted in a fiction or non-fiction film,” Miller said. “I wanted to include all these little moments that people who lived through it — mission control, flight controllers, someone who built a spacecraft — that they would like to see in the film. We would include them in the process.” They even tested out certain sequences on one of the key subjects. “We would cut a scene, then take it down to the IMAX theater in the Smithsonian and show it to Buzz Aldrin, just so we could get his response.”

But nothing beats the feeling of seeing the footage on a big screen for the very first time. After feeding the rare 65mm film through a revolutionary digital scanner — which took ages — they were ready to be the first person to see the images in nearly half a century. “We just locked the door in the screening room, and looped [the footage] with our jaws on the ground. We didn’t know what to say.”