Back to selection

Back to selection

The (Approximately) 30 Movies of 2021 Shot on 35mm

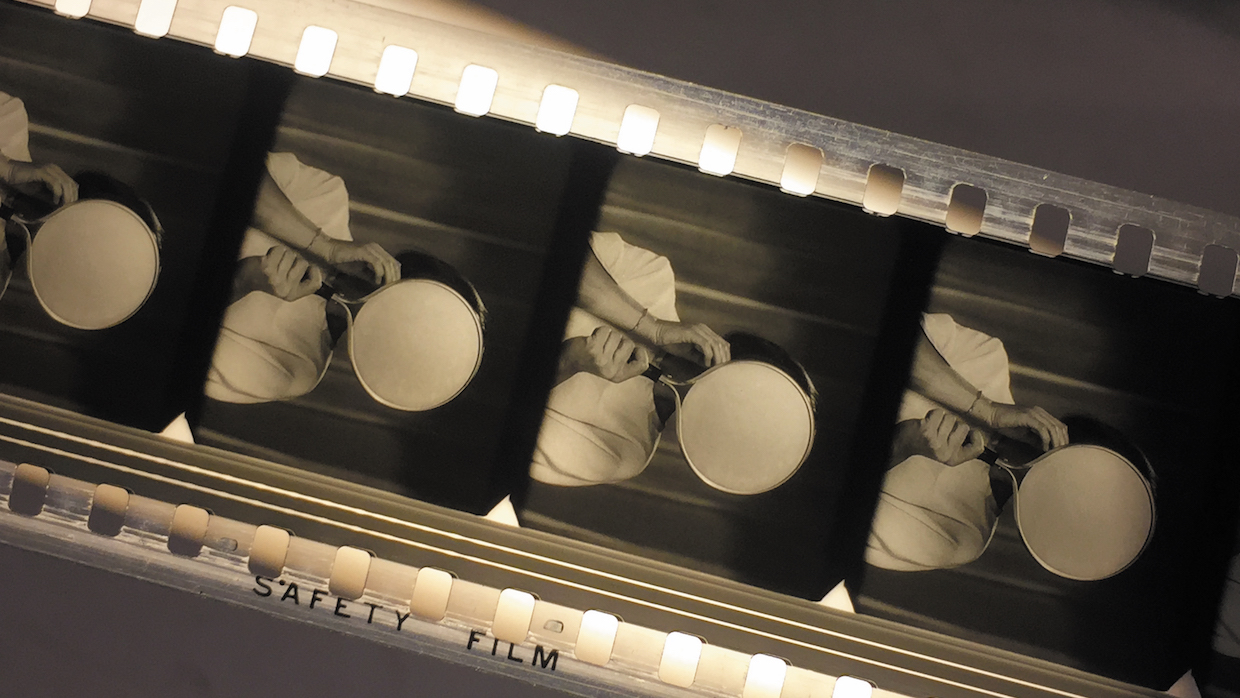

Image by Carolyn Funk

Image by Carolyn Funk As I began, for the eighth year in a row (!), to research the year’s U.S. releases shot in 35mm1, the two movie events I was personally anticipating didn’t primarily revolve around that format. One was Anthology Film Archives’s pandemic-delayed retrospective of Canadian experimental filmmaker, multihyphenate artist and all-round hero Michael Snow—initially scheduled for March 2020, finally screened in December and finished just before Omicron started surging around me. Most of his films were shot and shown on 16mm, making the few 35mm inclusions startling for their comparative, immediately perceptible sharpness and sheer volume. I went all in, taking a hint from the volume’s availability at Anthology’s box office and buying October Files: Michael Snow to read along with the films. I found myself stuck on this part of his “Statement for an Exhibition, Paris, 1992,” on the choices that come with photography: “in the first stage (taking the photo) these include framing, focus, exposure and lighting, but for me the choices made at this stage are also aimed at certain already defined decisions as to the final physical state of the print: whether it is to be printed on a surface, backlit or projected, also its size and shape, color grain and the mounting and physical placement of the photo/object in the gallery space […]”

Granted, this level of control from initial conception to optimal presentation is a gallery space luxury, never a standard filmmakers have been able to guarantee themselves. The other film event I was anticipating, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza, had accomplished that, at least for its first limited-run month, by the expensive expedient of being shot on 35mm but (per experimental film-world wording) optimally “finished” and presented on 70mm at only four theaters. PTA filmed The Master on 70mm and had 70mm blow-ups of Inherent Vice made, but Phantom Thread was the first time he’d committed to 70mm as the final necessary step—“because right now Kodak is trying to compete with digital, it makes their film stocks very, very fine grain,” his gaffer Michael Bauman told Indiewire’s Chris O’Falt in 2017. “So it’s about how do we get some of that dirt back, like some of the older stocks that were around 15 to 20 years ago.” Seen large on 70mm, Licorice Pizza immediately looked not just gorgeous but accurate in a way contemporary multiplexes rarely bother to guarantee—a large, in-focus image tended to by operators skilled in supersized equipment rather than a digital file degraded by an errant 3D lens darkening the image, dim projector bulbs or improper screen masking.

Among the 30 movies I tallied as being shot, in whole or substantive part, on 35mm and released in the United States in 20212, there were inevitably a few from directors whose loyalty to film has been so repeatedly established as to require no further elaboration. PTA is one; others are Steven Spielberg (West Side Story) and Edgar Wright (Last Night in Soho). The latter played in 35mm at six U.S. theaters, including Nashville’s Belcourt Theatre; programming director Toby Leonard wrote in an email that “Before DCP, we’d get uncut 35mm prints straight from the lab on the regular and thought nothing of it. Nowadays, one shows up maybe once or twice a year. The rarity of a 35mm run certainly does elevate things to a certain level in terms of turnout, but it’s hard to get a read on where that ceiling is. That said, it’s often the case that the nearest 35mm run is hundreds of miles to the north (Chicago or Columbus), and we’re the only run in film in the entire Southeast. In addition to the support we get locally, there are indeed some people who drive in from three hours away for the experience. We’re slightly hobbled these days by our 50 percent capacity, but the end result of a 35mm run does find us in the top tier of the highest grossing theaters for that film.”

Another of celluloid’s most vociferous advocates, Christopher Nolan, is now so associated with large-frame filmmaking on 70mm and IMAX as to represent a level of impossible luxury above even PTA’s. Hence, an unexpected pivot made by director Nicholas Jarecki, who discussed why he shot his three-stories-crisscross opioid drama Crisis on 35mm on the podcast “This Week in Start-Ups.” After noting that with 35mm, “You don’t need to do very much else than light,” and dropping the questionable statistic that “More than half of the nominated films last year were shot on 35mm” (Nominated by who? In what categories?), he was asked about shooting in 70mm by host/angel investor Jason Calacanis. “That’s IMAX, that’s Nolan,” Jarecki enthused. “I would love to shoot on that. Maybe you can sell some of your Uber shares and will them to me.”

On a less extravagant economic tier, returning celluloid loyalists included the admirably stubborn Philippe Garrel, who (like Aki Kaurismäki) has repeatedly said he’ll stop making movies altogether if he can’t shoot on film. Regarding his latest, The Salt of Tears, he told Christopher Small that extensive, long and paid rehearsals, while expensive, are financially balanced out by the resulting need for very few takes when shooting: “We save money during production on the cost of film stock, on developing, on everything. In the end, it costs the same as a film shot digitally.” Wes Anderson has shot all but his stop-motion features on film, and all but one of those (Moonlight Kingdom, 16mm) on 35mm. Speaking about The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, his usual DP Robert Yeoman told Kodak a lot of complimentary things. Speaking to ASC Mag, Yeoman allowed himself to make a mild complaint: “The disadvantage is that we shoot [Kodak Vision3 200T] 5213, which is [ISO] 200!”—i.e., requiring more lighting than, say, the oft-used Arri Alexa digital camera, which is rated at ISO 800 (the higher the ISO, the less light is needed). “So, we needed more light, particularly for nights and interiors, although we didn’t have to break our rule about ’fewer lights and light stands’ that often on this picture—only occasionally.”

Kodak’s site states that all Dispatch dailies were processed “normally”; i.e., with no pushing or pulling required by French lab Hiventy. A tweet by that lab that they processed Melanie Laurent’s The Mad Women’s Ball is the only confirmation I can find that this is a 35mm feature. For labs in general, what’s delivering dailies like currently? Paul Dean, a veteran colorist at Cinelab Film & Digital in the U.K., wrote in an email that “across the years I would say the most significant change I have seen, apart from the obvious technological advances, has been the diminishing gap between the cinematographer and colorist. The dailies colorist has become more of an extension of the camera crew, with the aim shifting from simply supplying editorial with images to ensuring those images accurately represent the ’look’ envisioned by the director and cinematographer right from an initial viewing of the footage. This is essential to ensure that the whole post-production pipeline—executives, financiers and crew—are dialed into the look from day one. […] With the advent of secure streaming services, we are now able to hugely narrow the time frame from shooting to dailies delivery. However, from a practical perspective, for a busy cinematographer at a difficult location, with challenging weather and a tight schedule, I always find that the eagerly awaited daily ’Report and Stills’ is the simplest way to quickly overview the footage.”

The biggest gap between what’s said to/published by Kodak and other outlets was courtesy of DP Denis Lenoir, in his third collaboration with Mia Hansen-Løve after 2014’s Eden and 2016’s Things to Come. That feature was digitally shot, unlike all her other films, because “the producer didn’t give her any choice,” Lenoir told ASC Mag. He acknowledges that “Mia, who has an incredible eye, doesn’t like the sharpness you get when someone crosses the frame laterally. Each image is extremely sharp due to the lack of motion blur. […] That can be simulated in digital, but it requires a lot of calculating power.” But speaking to the online publication of AFC, the ASC’s French counterpart, Lenoir said he “wasn’t at all excited” by her proposed return to film for Bergman Island: “I think that the increased sensitivity on digital cameras allows DPs to no longer have to light for exposure,” he says. “This is not at all the case in film, unless you unreservedly rely on underexposure, which I never used to do, since I always wanted to deliver a dense negative. But, on this film, I gradually set aside the wise precepts I learned in the Vaugirard cinema school.”

Lenoir’s reluctant caveat about film’s superiority for capturing horizontal motion is echoed by Lee Daniels’s regular DP Andrew Dunn. In a podcast with No Film School about his work on The United States vs. Billie Holiday, he told a story about using similar motion tests to wrest Crazy Stupid Love writer-directors Glenn Ficarra and John Requa away from their initial determination to use digital. As far as regularly shooting film with Daniels, Dunn notes that that there wasn’t much discussion about whether or not to work on celluloid when they first collaborated on 2009’s Precious. Digital was only “on the cusp” of taking over but still wasn’t hard to secure for this film, he says: “The producers totally got it” and having a lab in Montréal, where United States shot, helped logistically. Another low-key loyalist is Theodore Melfi, whose sophomore feature The Starling reteamed him with Melissa McCarthy, star of his similarly shot St. Vincent—in an email, Starling DP Lawrence Sher noted that Melfi “prefers the color and contrast and organic chemistry of film.” Romanian director Radu Jude has also regularly used 35mm, which he confirmed via email was the format for the first segment of Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn. (Here’s where I park a few other titles for which I could neither find nor obtain comment: the slacker singer-songwriter movie Hard Luck Love Song and City of Lies, a LAPD-investigates-Tupac-and-Biggie’s-killings thriller which first premiered in 2018 and straggled into theaters just as the first COVID wave hit the United States. Presumably, no one wanted to provide comment on it because it stars Johnny Depp.)

DP Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, who regularly works with film, is the only cinematographer with two titles on this year’s list. One is Ferdinando Cito Filomarino’s sophomore feature, the Netflix action film Beckett—I could find no statement for the reasoning, but it fits with both Mukdeeprom’s track record and that of his Call Me By Your Name and Suspiria director Luca Guadagnino, an avid celluloid proponent and producer on this. (According to a New York Times profile, Filomarino was also Guadagnino’s personal partner of 11 years until this past summer.) Mukdeeprom’s other credit was Memoria, his reteaming with Apichatpong Weerasethakul, for whom he’d shot all but one feature on 35mm, up to Uncle Boonmee Who Can Remember His Past Lives. In Mukdeeprom’s absence, Weerasethakul switched to digital for 2015’s Cemetery of Splendour but returned to his preferred format here; as he told Kodak, “Film reflects how I see the world and I even think that I see the world with this grain.”

M. Night Shyamalan’s Old marked his first time shooting a feature on the format since 2010’s The Last Airbender, and DP Mike Gioulakas’s first feature on it since 2008. Shyamalan announced his choice on Twitter in October 2020, in terms Kodak probably would have preferred be softened: “During quarantine made the difficult and costly decision to shoot on 35mm film. It was the best decision I could have made. There is nothing like film.” It’s not like he wanted to abandon film in the first place—“I always want to shoot in 35,” he said on a No Film School podcast—but there were problems: “It’s costlier. It’s more dangerous. It’s cumbersome. When I started making The Visit and these movies, I make them for so small that adding that extra money and cumbersomeness and difficulty, there’s so few crew members that know how to load a camera and how to take care of it—it felt extravagant for the way I was making movies.” But for Old, as he explained to Fox 5 Washington, D.C., reporter Kevin McCarthy, after digital vs. film tests he concluded that “only film could capture the complexity of sand and water. Maybe it’s because it’s so naturalistic, and the chemical process of film is also naturalistic, but the digital is grabbing the wrong information.” Shooting film during COVID added its own difficulty levels: Gioulakas used two film stocks rather than his desired three because, as he told Kodak, “My camera crew were under pressure to switch between different shooting modes in uncomfortable heat while wearing face masks the whole time.”

More pandemic productions: For Netflix’s Malcolm & Marie, as Sam Levinson told Variety, “We had already a lot of restrictions due to the coronavirus, so we wanted to elevate this and make it somehow a movie experience. One of the elements of that is the stock itself. […] The technical circumstances partly created the aesthetic […], you had to use less diffused, more direct light. The fact that it’s black-and-white also makes your lighting totally different. Shooting on film stock will automatically push you towards classic filmmaking, and you have to create each and every shot. You’re not lighting a set or a space and then you move around and tweak your lights a little bit. You really have to properly light every setup. By default, shooting on stock shapes your aesthetic.” Similar reasoning applied for Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World, shot over 54 days in summer 2020 on the writer-director’s default 35mm (he’s shot all but one feature on it), in this case partly as a response to pandemic privations: “One thing I missed in the pandemic was the big screen,” he told ScreenDaily, and wanted to maximize its qualities. “On 35mm, it’s the sensuality of the image that matters. We have tried to create a film where it’s almost like a big, visual musical.”

Filmmakers new to 35mm included Canadian directors Calvin Thomas and Yonah Lewis, who finally upgraded to it for their fourth feature. Like Bergman Island, for White Lie “we shot 2-perf,” they wrote in an email. “Shooting film wasn’t a question for us the moment we had a large enough budget to accommodate it (our previous film had a budget of about $5K). Film simply looks better. We originally thought we could only afford 16mm, but it didn’t seem quite right for the project. So, we pushed for 35mm and worked with Panavision here in Toronto, using their Super 35mm 2-perf system to get the most out of our mags. The resulting image worked well for the film, halfway between 16mm and 35mm in grain structure. A bit of a rougher image, but that suited the realistic world we were after. We ended up having a pretty healthy ratio of 13:1. To be honest, most days we weren’t running out of film, we were running out of time. We had so few shooting days we were limited by the schedule and not the format. Think this is pretty common and, for us, put to rest the myth that shooting on film reduces the number of takes you can accomplish in a day.” Making her feature debut, Beginning, Georgian filmmaker Dea Kulumbegashvili was at an advantage because she and her DP, Arseni Khachaturan, had already shot a short on 35 before. Unlike other filmmakers and DPs quoted above, she doesn’t stress lighting: “Since we almost had almost no film lighting on this film, we tried to just keep it to practicals and keep it to natural light, and I had huge creative arguments about how much dark you could film,” she told MUBI’s Daniel Kasman. “When we were looking at the footage, in some of the scenes you could see every single dust particle, and it was incredible how much you can really work on light.”

Per usual, numerous productions included 35mm as part of a mix of formats. On the highest budgetary end, there was No Time to Die, where 35mm (some 1,007 rolls were shot) sat alongside 65mm and IMAX, and Space Jam: A New Legacy. “The two primary capture mediums were 35mm Kodak film and the entire lineup of Arri cameras, mainly the LF,” colorist John Daro wrote on his website. “The show can basically be broken down into two looks […] the real-world and the Warner Bros Serververse. We chose an analog celluloid vibe for the real world. The Serververse has a super clean, very 1s and 0s look to it. Most of the real world is shot on film or is Arri Alexa utilizing film emulation curves paired with a grain treatment. Some sequences have a mix of the two. Let me know if you can tell which ones. [smiley face emoji]” Picking up where DP Charlotte Bruus Christensen left off in the first film, Polly Morgan shot A Quiet Place Part II mostly on 35mm, in part to keep with the first film’s look. Speaking to Kodak, she said that “You hear so much technical rhetoric about digital having more latitude than film, but that’s simply not true. We worked in some very dark situations, really pushing the negative to the limit, and film held it beautiful.” Speaking to Variety, though, she noted a few situations where she had to shoot digitally: “an arena scene at night on digital because we could use its sensitivity to see out into the water at night,” as well as a scene shot inside a Volvo “because we simply couldn’t fit a film camera in that car to get the shots we needed.” Speaking to Daniel Eagan at Below the Line, DP Stephen F. Windon estimated that “about 20 percent” of F9 was shot in 35mm. The Fast and Furious franchise’s last installment to shoot on 35mm, number six, was shot in 2012, but F9’s flashbacks to 1989 allowed for a period-appropriate return to film.

While shooting daytime-film/nighttime-digital is a common enough split, for Spencer the unusual decision was made to shoot the majority of the day scenes and interiors on 16mm, while using 35mm for night exteriors, “when we didn’t want to show too much grain in the image,” DP Claire Mathon told Kodak. “For those scenes, the 35mm allowed us to retain softness and detail in the dark areas, while keeping fairly fine granulation in the overall image.” Similarly, on Jonas Carpignano’s A Chiara, DP Tim Curtin told Indiewire he shot most of the film on 16mm but occasionally would “switch to 35mm or utilize stabilizing rigs in order to differentiate sections of the film visually, depending on the narrative and emotional moment.” The year’s biggest mix of formats was probably Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir Part II—a total of seven capture mediums, including no less than two varieties of 35mm. “Because this was a film about the filmmaking process itself, especially of the main character Julie, a student filmmaker, the texture was also supposed to reflect on this,” DP David Raedeker wrote in an email. “It was not so much about giving it a period look, but more having multiple textures reflecting the different levels of filmmaking: student films, a high-end musical, news reportage, etc. In the end, we ended up with seven different formats, two of them on 35mm film: Garance’s [played by Ariane Lebed] student film on 35mm Academy and the musical on 35mm black and white stock anamorphic. These were only two short scenes and around 80 percent was shot on 16mm film, including the student film with dream sequences at the end.”

In Macedonia, director Teona Strugar Mitevska shot most of God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya digitally, but used 35mm to capture exteriors because, as she wrote in an email, “we were concerned with having detail in the sky as well as detail in the white snow. We used the 35mm camera from Vardar film, the state agency from Yugoslavia times. It’s a camera that’s rarely used and never serviced, but it worked for us. It’s the same camera I used for Veta, my short film many, many years ago.” My biggest sympathies are for similar underdogs who work hard to get 35mm even when money and infrastructure is an obstacle. For her feature debut film, the 1980s-set Censor, Prano Bailey-Bond always planned to shoot film—“indeed, that was part of Prano’s initial pitch for the funding,” her DP Annika Summerson told Kodak. For Hungarian production Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time, DP Róbert Maly wrote a three-page document for prospective private financiers and government agencies explaining why shooting on film was vital. Then, the obstacles really began: “The last time the film laboratory in Hungary used their machines was about a year before our film,” Maly told Kodak. “It took some time to get the proper color temperature.” The camera was a 3-perf Arriflex ST that used 400-foot magazines, which wasn’t exactly a matter of choice: “It was hard to find the best camera for this because in Hungary at that time there was only one camera and one magazine that were usable. We had to rebuild three other magazines. The setup was unstable. It was a huge camera. I could not hold the camera for a few hours to make one shot because it’s 27kg, so we put it on a tripod.” The environment posed its own infrastructural lighting problems: “We had a lot of problems with the classic neon tubes. All of the post-Soviet countries have their own greenish lights which are really different. Sometimes for the lighting setups we were careful to shoot at dusk or dawn because it was important not to practically light the shot.”

In the end, the number of films shot on 35mm didn’t differ meaningfully from my last few years doing this roundup. I’ll give the final word this time to Cinelab’s Paul Dean: “We have 10 photochemical lab staff out of a total team of 37 […] Since establishing [the photochemical lab] in 2013, we have seen sustained growth in demand for film, with over a 10-fold increase between 2014 and 2019. The COVID years have had an impact on overall footage processed, but mainly due to a downturn in the major studio productions at that time. However, we have continued to see sustained growth from independent films, HETV, commercials and music promos throughout this period, and there is no doubt a desire for people to see content acquired on film, from Super8 through to 65mm. We anticipate 2022 being our biggest film year ever.”

1. In previous years, I’ve relied upon Mike D’Angelo’s list of films that had one-week NYC runs to determine their “U.S. release” status. In 2021, for obvious reasons, the list he shared with me also included streaming releases that got New York Times reviews—basically an “I know it when I see it” overview of what might reasonably count as 2021 releases.↩

2. Post-publication correction: I missed at least one title, Don’t Look Up, from 35mm loyalist Adam McKay.↩