Back to selection

Back to selection

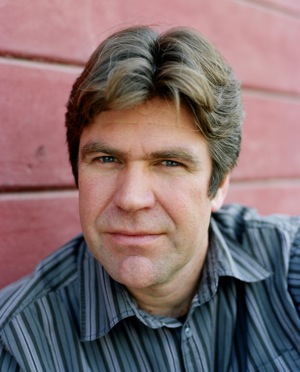

Director Greg Barker on Koran By Heart

Koran by Heart, premiering on HBO today, comes out at a time when it couldn’t be more necessary. In the wake of July’s attacks in Norway and the Islamophobic response in Western media outlets, the film offers a composed perspective of life in the Muslim world.

Koran by Heart follows three Muslim youths — Nabiollah from Tajikistan, Rifdha from the Maldives, and Djamil from Senegal — as they enter into an annual Koran-reciting competition in Cairo, Egypt. The competition attracts hundreds of Muslims from all over the world, many of whom don’t speak Arabic, but are able to recite the entire 600-page Koran — and beautifully.

While some critics have described it as “Spellbound in Arabic,” Koran by Heart concerns itself with matters beyond the contest. Director Greg Barker, who made Sergio for HBO and a slew of PBS Frontline docs, approached the project as a means of exploring the internal conflict in Islam between modernity and fundamentalism.

“I think that what we’re living through — this era of fundamentalism and Jihadi extremism — all comes out of this struggle within the faith itself,” Barker said after his film showed at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival. “I really wanted to get beneath the surface of the competition and the kids’ stories to try to get into that. […] I had a feeling it would be through the stories of their education.”

Indeed, as the kids leave their homes for the competition, their schools are subjected to government crackdowns on Islamic extremism. Nabiollah’s school is shut down, while Rifdha’s is divided into religious and secular divisions. When this religious conflict isn’t conveyed through events, it manifests itself in the film’s few interviews. Rifdha’s father speaks of the dearth of “good Muslims” in Cairo, while the contest’s primary judge, a well-known Islamic moderate, attributes the “irresponsible actions you see in some Muslims” to their misinterpretation of the Koran.

So we’re left with a talented and impressionable group of kids who can memorize the entire Koran, but can’t understand its meaning. As they advance from round to round, the suspense heightens not only in terms of the competition, but in terms of their futures. Will Rifdha, a bright girl with dreams of becoming a deep sea explorer, be able to escape her father’s expectations for her to become a housewife? Will Nabiollah, an angelic boy with a photographic memory, learn how to read or write? Is Djamil destined to become a local imam like his father? And what is at stake in these questions?

Filmmaker sat down with director Greg Barker after Koran By Heart premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival. We discussed his process of constructing the film, the difference between making documentaries for television vs. theatrical release, and Western (mis)perceptions of the Muslim world.

Filmmaker: How did you past in journalism inform your experience making this film?

Barker: I’ve been lucky enough to go to a lot of Islamic countries. And most of that came out of my journalism work and my work for Frontline. I’ve been intrigued for a number of years with the internal discussion within Islam over the direction the religion should take, broadly speaking between more fundamentalist-conservative viewpoint and a viewpoint that is more accepting of modernity. I really wanted to get beneath the surface of the competition and the kids’ stories to try to get into that. I didn’t know quite how it was going to happen. But I had a feeling it would be through the stories of their education. So I think my journalism background helped me frame the bigger issues I wanted to somehow touch on in the film.

Filmmaker: Was it difficult for you as an American to gain the trust of your subjects?

Barker: When I go to these countries that are not my own, I just go in with open eyes and listen. And I think that was the key to being able to make this film. My whole team and I were very respectful. We didn’t pretend to know anything about these subjects. We were entering this sacred world, and we just had to keep an open mind and listen to why it was important to people.

Filmmaker: One of the successes of the film is that it conveys that there is, indeed, a vision of Islam that isn’t synonymous with a militant defense of Islamic beliefs. It doesn’t got to lengths, however, to explore the point at which the Koran can be co-opted to fit a more extremist base.

Barker: This is not really an investigative documentary. For me, I can reach a wider audience and raise more issues if I’m making a film that plays as a movie first and foremost, and then the other issues are just kind of there. I think everything’s there, in my opinion. Nabiollah’s school shut down because the Tajik government was worried about schools like that spreading Islamic extremism. If you’re looking for the sense that Islam can be distorted, and that these kids can be brainwashed, I think you can find it in the film. It can happen, clearly. The fact that this very bright, ten year-old boy who basically learns nothing but the Koran eight hours a day or more — is that right?

Filmmaker: How would you explain this internal conflict within Islam?

Barker: Well, in my opinion, it largely has to do with the extent to which Muslims should embrace modernity and the outside world, the non-Muslim world. Christianity had a reformation. Islam has never had a reformation. Many Islamic moderates believe that now is the time to have that. It’s a faith that was at its peak, in terms of political power, arguably 1,000 years ago. It was a rich and powerful movement. That has changed. And I think there’s been a search for a way to restore that former greatness. Some say they should go back to their origins, and some say you actually have to modernize the religion. I think that’s something that they’re going to sort out themselves. And I think that what we’re living through — this era of fundamentalism and Jihadi extremism — all comes out of this struggle within the faith itself.

Filmmaker: What would you say to non-Muslims who believe the polarizing rhetoric of the War on Terror?

Barker: If [you’re] non-Muslim, all [you] can do is try to understand it. Because saying that Islam is a violent religion doesn’t get you anywhere. That can be said for all religions. You want to ban Islam around the world? At one point there are 1.6 billion muslims in the world. It’s not going to happen. So the better approach is to try to understand it. And by understanding it, I think that one realizes that there’s more nuance than is often portrayed. And that’s what I try to get at in the film. For me, these kids are all on the cusp — particularly Nabiollah and Rifdha. They’re going to get caught up in the political turmoil that surrounds their religion. It will happen as they enter adulthood. What course are they going to take? It’s entirely up for grabs. And that is a very real struggle that Muslim families are facing all around the world. Which way will they go? it’s up for grabs.

Filmmaker: What do you think are the implications of your subjects memorizing the entire 600-page Koran without speaking Arabic?

Barker: I think it depends on the context and on the kid. It can clearly be seen as a form of brainwashing. Or it can be seen as a form of religious devotion. And it’s probably either or both depending on the circumstances. What I would say is that the Arabic of the Koran is very ancient Arabic — old Arabic analogous to old English. So when people are memorizing it, particularly at a very young age, it’s a very complicated language. It’s not the kind of language that any ten year-old is going to understand anyway.

But clearly if they’re studying it and don’t have any sense of what it means, and it carries on over time, then that raises some questions. And I think it’s hard for an outsider to answer those questions. Because unlike the Bible, which can be translated in any language, Muslims consider Arabic to be the language of the Koran as revealed by God. So although you can translate it, the translations are not the holy Koran. They don’t have the same reverence as the Arabic translation. So when Muslims around the world go to mosque they listen to and recite the Koran in Arabic whether they speak it or not. And then it is interpreted for them by an Imam or leader who tells them in their own language what is means.

Filmmaker: What was it like for you to premiere the film at the Tribeca Film Festival, ten years after it was founded to revitalize the Lower Manhattan area after the 9/11 attacks?

Barker: Honestly, I had no idea how the film would play. It’s a very foreign subject for a Western audience. So the challenge [was] taking somebody into that world and making sure they don’t feel lost. What’s amazing is that by the end, the audience [knew] who’s a good reciter and who’s not such a good reciter. [They were] rooting for kids. An hour and half before that they would have had no idea. So people [were] very responsive.

Filmmaker: In the Q and A following the screening, one audience member questioned Rifdha’s father for forbidding his daughter to pursue an education. Out of respect for the family, you stepped in and shut down the conversation. What sort of questions do you hope the film raises?

Barker: I think in a situation like that, my primary concern [was] for the family that traveled 8-9,000 miles to come here. And I [wanted] to make sure that they [felt] comfortable. The questions that [were] being raised are exactly the questions that I hope people would have. It’s on everyone’s mind, particularly because Rifdha is this amazing little girl, and it’s so shocking what her father says.

Filmmaker: So what about the status of women in the Muslim world?

Barker: Well, I think it’s part of this internal discussion within the faith. In the film, the head of the competition says, “We believe men and women are equal.” So Cairo is the only major competition where they actually allow girls to compete with boys. It’s one of the reasons I chose it. I think there’s a lot of Islamic women who have very strong reactions, saying, “There’s nothing in the Koran that prohibits a woman from working and being educated. She doesn’t have to be a housewife.” I think there are muslims who disagree with the father, who will say that, “Look, there’s a difference between the Koran, which is a holy religious text, and what is called the Hadith,” which is the stories about the way Muhammad lived his life. Which is not part of the Koran. A lot of the interpretations that we hear about how a Muslim must live his or her life often come from the Hadith and not the Koran. There are thousands of Hadiths. It’s not the religious book itself; it’s an interpretation of how one should live one’s life. And that’s where a lot of the controversy comes from. Because that contradicts itself a lot of times.

Filmmaker: What to you are the advantages and disadvantages of making films for television vs. making films for theatrical distribution?

Barker: I would just say that [when] making films for HBO, you always make them with a cinematic mindset. So in my mind they qualify as theatrical experiences. Whether or not it has its initial release theatrically, the approach is the same in terms of filming. Very different from the approach that I would’ve taken when I was doing PBS documentaries.

Filmmaker: What was your experience with PBS like?

Barker: Well, I had a phenomenal run making films for PBS. I was based out of London. I traveled all over the world, and did films on Afghanistan, Rwanda, the Middle East, China, everything. It was great. I think the main difference is that PBS has a reputation to educate. And I came to the conclusion that I could reach more people and actually educate in a broader sense by making films that didn’t try to educate, that actually tried to tell stories and work as films. In my opinion, they would actually learn more than something where the narrator or interviews are telling them what to think.

Filmmaker: To what extent were the people at HBO involved in your process?

Barker: The process [was] very collaborative. The idea [for the film] actually came out of discussion I had with my two producers, John Battsek and Julie Goldman, and Sheila Nevins [President of Documentary and Family Programming at HBO]. I had been looking for stories that might get into this divide within Islam that I’ve been talking about. And Sheila had heard about these contests. She said, “Have you heard about these Koran reciting competitions?” And I said, “No I haven’t!” So they’re completely supportive. I was on the phone from Cairo, saying, “I think it’s all going to work.” And Sheila was like, “If you think there’s a film there then we’ll support you.” They’re such film-friendly execs. I genuinely think that they’re courageous executives and are so supportive of filmmakers to find stories and follow their vision.

Filmmaker: What emotional toll do these kinds of projects — on intense subjects such as Islamic extremism or the Rwandan genocide — have on you?

Barker: Well it depends on the film. Making a film about Rwanda [Ghosts of Rwanda] was miserable.

Filmmaker: That was a seven-year effort too, wasn’t it?

Barker: It was. And it was so awful. Nothing compared to what the people who told their stories went through, obviously. But it was a deeply emotional, draining experience. And Sergio was also intense. Generally, it’s the most rewarding experience to be out there in the world and engaging with issues that really matter to people, and trying to find ways in. Stories that work as stories, that connect our audiences to issues that they otherwise wouldn’t connect with. Stories that connect an American audience, a Western audience, with the rest of the world in a way that is visceral and entertaining, and feels relevant. And I love it.