Back to selection

Back to selection

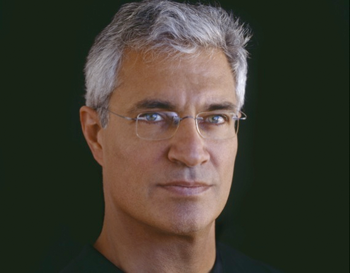

Photographer/Director Louie Psihoyos on The Singing Planet

Louie Psihoyos started out as a still photographer for National Geographic. He won an Oscar for his first feature length documentary: The Cove, which took an unflinching look at the slaughter of dolphins in Japan. He is now starting work on his next film, The Singing Planet, which will be shot underwater using extraordinary sound recording advances. He took a moment to talk with me about his films and his work as an environmentalist.

Filmmaker: How did you get interested in still photography? How did you start working as a photographer?

Psihoyos: I loved making art when I was a kid. I think that’s what got me into still photography, that I could make instant art. When you are drawing or painting it can take days or weeks to make a piece of artwork, but with photography you could do it relatively instantly. I drew birds. I drew wildlife. I wanted to be a photographer when I saw National Geographic at my mom’s hair studio. I was about six years old. It was an article that Jim Blair had done on Easter Island. That just blew my mind. Who are these people? Where did they come from? How did they disappear? All these unknown questions that became this metaphor for adventure and excitement. We didn’t know anything about those people. We still know almost nothing about those people. It excited this adventure in me, and that’s really where it all began. You know it’s sort of a cliché that anybody that grows up wants to be a photographer for National Geographic. I never took it that people didn’t actually become that. When I started working for them I became the first photographer that they hired in eleven years. If there’s a lesson there for me, or anybody else that cares, I guess: never give up on your dreams.

Filmmaker: How did you come to be the first photographer they had hired in eleven years?

Psihoyos: Back then, they would take three interns every year. College interns. They take two by portfolio and one by winning a contest called College Photographer of The Year. So I applied for the internship by portfolio, and I got a very nice letter back from the director of photography who said to me, “You’re good enough to shoot. Internships are only good enough for people who aren’t. Good luck in your career.” And I was heartbroken. I was a junior in college and I thought: my God, how am I ever going to work for them if I don’t get in as an intern? And then I thought: Well, there’s this contest. So, I worked real hard for nearly a year. I worked for the LA Times during the summer and I had a portfolio. There were about six or seven categories: sports, portrait personalities, and storyboards, and so on. I won first place in six or seven categories. They had to hire me. That’s how I got in.

Filmmaker: What did you shoot for them?

Psihoyos: The first story I shot was a black and white story on the Powder River Basin. It was just up here in Wyoming, where the environment was being changed from a ranching community to a mining community. The Powder River Basin is where they have one of the largest reserves of coal in the world. A lot of our coal in America goes over to China because it’s a low sulphur coal.

Filmmaker: Were you choosing your stories or were they assigning them?

Psihoyos: That story was assigned to me when I was an intern. Then my internship was going to be over at the end of the summer and I had to quickly think about something to do. Well, do you want the long story or do you want the short story?

Filmmaker: I want the long story.

Psihoyos: There was a really wonderful, creative person there I met, who started about the same time as I did. He was helping lay out the magazine and Geographic was doing stories at that time about gold, silver, platinum, rubies, diamonds, and there was one photographer who was mainly shooting that – his name was Fred Ward. We were kind of making fun out of Fred’s stories, they were wonderful stories, but we thought the National Geographic had such a romantic view of the world, you know they have these relentlessly optimistic stories, like they could make Zaire look like a good place to live during a civil war. They had this notion that you never show the dark side of life, and I was all about trying to show the dark side of life. Not only that but try to make it interesting and entertaining. Anyway, we were up in the cafeteria over lunch time and we saw somebody hauling the garbage across the lunch counter and this was at a time when Geographic had separate lunch rooms for the men and the women. This was back in 1980. It was a very southernly type of atmosphere. It was a very regimented society. So, there was a woman hauling the trash across the lunch-room floor and I thought “Do a story on trash!” You know, like Fred Ward would do it – we could do: “Garbology: the study of garbage.” Well it turned out there is this guy Bill Rathje – this archeologist who studies modern trash, that’s what archeologists do. The best thing they can do is to find the trash of an ancient culture to figure out who they were, and they would make all these extrapolations. I thought there is this colony of people who make art from trash up in California, there might be a story for National Geographic. I wrote it up and that’s how I became the first guy that they hired in eleven years. I did the story. It was an environmental story, it was on garbage, but then I realized that for the next nine years of my life I would have to make garbage look interesting. I traveled all around the world, got to some amazing places, stayed in five-star hotels, but I was shooting garbage. It became one of the most popular stories in their readership survey. They kept on hiring me. I was still three credits short of my graduation, I didn’t go back to school to finish my college career because I already had my career.

Filmmaker: Did the work make you more environmentally conscious? Or did the consciousness come first.

Psihoyos: Back then I was very environmentally conscious, when I was 17 years old I was helping protest a nuclear power plant with Pete Seeger. That was one of the first stories I did, and then everything I was doing I was trying to be socially conscious and then I started working at Geographic and I did the Powder River Basin story, the garbage story, and then I got very good in my career at pulling rabbits out of hats: visually, trying to make stories that were not so exciting. They thought we have this kid, we could dump these stories on him and he could do them, and I was quite eager to work, but it sort of brought me down this road that I didn’t necessarily want to go on. I weened myself away from Geographic and I did more interesting, important stories, I thought, when I moved up to New York. The irony is that I had my dream job. There was nothing in the satisfaction level to say that I was unhappy. But I feel like that was the wilderness compared to what I am doing now. I feel like this is so much more fulfilling, it’s using the same thing, you are using art, you’re using moving pictures to tell a story in a very provocative way. You’re using sound, and not just my talent, but the talents of all these people that I have working here. We end up working together towards this big goal. When you take pictures, even for National Geographic, I was only allowed to have one assistant. Now I have a whole team, and that’s sort of a curse and a blessing at the same time, because you have to get five people up at the same time in the middle of the night – to get the really good stuff you have to be up early. You have to work hard, really hard. Most people, don’t understand what it takes to get the kind of images that we get. You have to have this relentless pursuit of perfection. To get up and get the shot – because the nature, the environment, the weather, they are not always cooperating with you, so you have to be there and be there and be there. So in this world, where they want to know what you’re going to do on this day – what I do is if it’s not the perfect day, I try to go find something else to do, I try to be creative. To me, the story is always changing.

Filmmaker: When did you decide that you wanted to start making films?

Psihoyos: About five years ago. My dive buddy was Jim Clark, the guy who started WebMD. One of the jobs I had was shooting covers for Fortune Magazine. That’s where I met Jim. He was a legendary guy already. I had actually wanted to photograph him for a story that I was doing for National Geographic on the information revolution. He was too busy back then, he was this demi-god in that world. Then I photographed him and we became best friends, and dive buddies. About seven years ago now, we were on our third trip to the Galapagos. We were watching fisherman illegally fishing in a Marine sanctuary. He said something like “some one should do something about all these problems.” I’ll set this up a little bit. Jim is sort of a Zelig in the business world. When he was a professor at Stanford he created the first three-D graphics engine, which is the way that you do things in 3-D in real time on your computer, now we take it for granted, but that sped up the manufacturing, the productivity, the design stage, which became much more intuitive because of the real time computer chips that he built. The day he quit Stanford he started Netscape, the first commercial internet browser. The third company, WebMD, he told me was just to prove that the first two billion dollar companies weren’t a fluke. I used that business to save my mom’s life. I found out through WebMD that they were over medicating my mother, so he helped save my mother’s life. So when Jim said, someone should do something about this – about people fishing on marine sanctuary illegally – I was like “Well, how about you and I?” I felt emboldened to make that kind of a statement based on who he was. He’s a guy that changed the landscape of our environment. So we started this non-profit called Oceanic Preservation Society (OPS). The idea was to use his money and my talent as a filmmaker to make movies. The only problem was I didn’t have any talent as a filmmaker. I had never made film before. But I was very good at researching, and I had a good nose for a story. I went to a marine mammal conference and Ric O’Barry, the trainer for Flipper was supposed to talk there. And they wouldn’t allow him to talk, and I thought: “Who’s the sponsor who wouldn’t allow him to talk?” It was Hubbs Sea World Research Center. I called up Rick and said, “Why wouldn’t they let you talk?” And he said “ I was going to talk about this dolphin slaughter in Taiji. I had never heard about dolphins being killed before like this and I said, “Whose doing anything about this?’ and he said “Just me. I’m going to TaiJi next week, do you want to come?” I said, “I can’t leave right now.” What I didn’t tell him was that I had to take a three-day crash course in how to make a film. Then I caught up with him.

Filmmaker: Tell me about making The Cove.

Psihoyos: The joke on the set of The Cove was: We’re all professionals, just not at this. When someone came into our life we would think: How can we use this person. Mandy-Rae Cruickshank, she was coming over to Japan to shoot divers that were diving for pearls. I thought we could really use them to set cameras in the cove. We had this team that we put together, but it was using their skills to help solve these problems. If it’s a lawyer, I think well – “Sue the bastards, you know – we need litigators.” If you’re a writer, “We need writers.” It depends on who you are. You can be very very effective using what somebody’s real skill set is. That’s sort of our brand around here, we bring people together with different specialties and then we try to figure out ways to amplify their voice, to amplify their bigger messages. I feel like I’m just the person who helps turn up the volume. People start to hear it, it starts to resonate at a frequency that people can actually see and hear using stories.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about your new film and the challenges of shooting underwater?

Psihoyos: It’s a big story. It’s a complicated story. I am excited, because I see a way emotionally into a big story. I was talking to James Cameron about it last year at about this time, and he was saying “You have to make the story emotional. You have to make it so that they don’t just understand it intellectually, but they actually feel it, deeply.” Your emotions are what make you change behavior.

The working title of the film is called: The Singing Planet. Chris Clark, a biologist from a bioacoustical laboratory up at Cornell, said, “The whole world has been singing, we just haven’t been listening.” Everything from insects up to blue whales, has a voice, has a song, we don’t even recognize it as a song because we think that only humans can sing. We know birds can sing, but almost everything with a backbone has the ability to make sound, and when you go underwater the first thing you hear is the crackling shrimp. You hear the shrimp singing down below. A blue whale sings, but you can’t hear most of what a blue whale is singing because it’s below our threshold for hearing. You can feel it though, if you’re in the water, you vibrate, you know something is there. It’s almost like an earthquake. Even if you could hear it you wouldn’t even recognize it as a song because the notes are like 70 seconds long. So, our internal metronome for how we perceive sound and music noises is completely different than a blue whale. It’s still song, you speed it up it sounds like bird song. I just love that as a metaphor. We are losing these voices extremely quickly. We’re trying to capture these sounds. We’re doing it with DSD technology – it’s never been done with film before, it’s almost like 3D sound. I love to take people to our studio and show them the sound because it’s transformational. You see it in everybody’s eyes. There’s a high bit rate, a high sampling rate is like 48 k, 192 – this is like 2.8 million. If I am talking with DSD technology, you close your eyes, you feel like you could touch my lips. It’s that clear, it’s that resonant. So, you capture the emotion in people’s voices, you capture the emotion of song. Technology for music is going the wrong way. We have dumbed ourselves down. It’s oxymoronic because as our ability to capture more bits has gone up we have sacrificed quantity for quality. We all have a thousand songs on our iphones, but what we are missing is the soul. We’re missing the true clarity of the voice. That’s what we hope to bring back with this film. When people start to resonate, they start to vibrate with these creatures, and they start to hear them and feel them, you have this deeper connection.

Filmmaker: Do you have a projected date of completion for this film?

Psihoyos: About this time of year 2013, two years from now.

Filmmaker: I can’t wait to see it.

Psihoyos: Film is the most powerful weapon in the world. I call it the weapon of mass construction. You can use it to sell boxes of popcorn and get ten dollars for a ticket, or you can use it to change the world.

To read more from Lambert’s interview with Psihoyos, go to The Great Immensity.