Back to selection

Back to selection

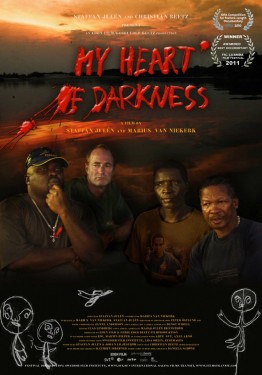

Director Marius Van Neikerk on My Heart of Darkness

Marius Van Niekerk of "My Heart of Darkness"

Marius Van Niekerk of "My Heart of Darkness" The journey of an international documentary to the United States is an uncertain one. Make its subject a lesser-known foreign war and the post-traumatic effects thereof, and you’ve got what an American agent calls a “hard sell.” My Heart of Darkness, a brooding foray into four veterans’ pasts, has been traveling the international festival circuit since premiering at IDFA in 2010. The years between then and now, where it’s having its U.S. premiere at L.A.’s Pan African Film Festival (PAFF), has been marked by all manner of revelations and misunderstandings—appropriate for a film about the reconciliation of four former enemies of the Angolan Civil War.

As its title suggests, My Heart of Darkness is a personalized take on Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness. The documentary, directed by Staffan Julén and Marius Van Neikerk, applies the symbolic thrust of Conrad’s book to a meditation on war’s disgrace. The transfer of Conrad’s story from the Congo to neighboring Angola is more than arbitrary. Just as the West used the Cold War as a pretext to intervene in Congo’s affairs—leading the CIA to back the assassination of the country’s first democratically elected president—Angola became a major site of Cold War intervention.

The Angolan Civil War pitted the United States and South Africa against the Soviet Bloc and Cuba. Central to the conflict was the issue of who would control Angola after it gained independence from Portugal: the communist MPLA or the anti-communist UNITA. The war continued sporadically for over thirty years, fueled by competition over the country’s wealth of oil and diamonds.

My Heart of Darkness joins co-director and writer, Marius, who fought for the South African Defense Force (SADF) with three members of Angola’s Civil War: Patrick, who fought for the MPLA; Samuel, who served for UNITA; and Mario, a South African indigene whose affiliation was ever-changing. In a series of riverside conversations, the men recall the atrocities they committed and the names in which they committed them. Rather than come to any understanding of the war’s logic, they can only agree on its senselessness.

I first spoke to directors Staffan Julén and Marius Van Niekerk in Amsterdam for their world premiere. At the time, Julén said of the documentary: “We wanted to make a universal film about war veterans and what war makes of you…After a while, my hope was that the audience would stop thinking about whom so-and-so was fighting for. Because what mattered was what they did and how they dealt with it. Then we tried to limit the historical information as much as we could, and frame the story through Marius’ point of view. To tell what he knows about it, and also what he doesn’t know about it.”

Due to meager festival budgets and scheduling conflicts, Marius Van Niekerk is attending his film’s U.S. premiere by himself. Filmmaker caught up with him on the phone to talk about the film’s life since its 2010 premiere. My Heart of Darkness screens at the Pan African Film Festival on February 13th, 15th, and 17th. For more information, visit PAFF’s website.

Filmmaker: The film has lived quite a life since the last time we spoke. Can you map out its trajectory leading up to its US premiere?

Van Niekerk: We had some kind of trouble…We had an agent in the beginning, and then the agent made demands. They asked us to change the voiceover of the film and to recut it. And we didn’t want to, so we lost the agent. We were supposed to go to Sundance and Hot Docs and Tribeca and the whole trip. And all that fell through. It was very frustrating. But after IDFA, it was in competition at the Gothenburg Film Festival. Then it was at the Tempo Documentary Festival in Sweden. Then I was invited to the Tri Contintental Human Rights Film Festival in South Africa. Then, Staffan [Julen] went to South America where it was shown. Then it was shown in Belgrade, Serbia. And the next festival it’s going to show at is Brighton in the UK. So it’s picked up recently.

Filmmaker: I remember getting an email from you a while ago in which you mentioned the possibility of changing the voiceover for the American premiere. I remember being surprised at the suggestion since the film is about your experience of the war. It’s framed through your perspective. And I thought that an American’s re-telling of that experience—let along a name actor’s—would strip the film of its personal quality. What was your agent’s reasoning for that suggestion?

Van Niekerk: Their reasoning was that it would be better for the American market if we had a known American actor [doing the voiceover]. But now we have a new agent, Journeyman Pictures in the UK. They’re interested in taking My Heart of Darkness, and we’re cutting a 52-minute version for broadcasting at the moment. And then hopefully it will get onto international television.

Filmmaker What was it like for you to take the film back to South Africa, the country that sent you to war in the first place and from which you’re now an exile?

Van Niekerk: The first screening [of the Tri Continental Human Rights Film Festival] was in Soweto outside Johannesburg. During apartheid, Nelson Mandela and all of these activists of the African National Congress (ANC) were living there. The heart of the liberation struggle was born in Soweto. During my time in national service, the white troops were sent into the black townships to fight the ANC. So in Soweto, I was shit scared because I thought, “My God, some years ago white soldiers were here in the townships killing black people.” Most of the audience was black. Afterwards it was dead silent. And after ten minutes of standing at the front looking at this audience, one black guy got up—he was about my age, probably in the war on the other side—and he was crying, and he gave me a hug in front of everybody. And [the audience] was all ANC veterans. They came and hugged me and shook my hand and we had this amazing discussion about the war and reconciliation afterwards. Just incredible.

Filmmaker: The film portrays your reconciliation with your former enemies—a process that has closure, but is also left open-ended. Does your ability to deal with your past become easier when you’re showing the film around?

Van Niekerk: After South Africa, I went to Angola and had a couple of screenings at the Luanda International Film Festival. And we got the prize for Best Documentary. That was kind of the end of that road for me, the end of my long journey towards my personal reconciliation. It was an acceptance. I’ve asked for forgiveness and have been given that. I’ve been forgiven. So the screenings in South Africa and Angola was the end of that journey for me, in a way. Now, when I have screenings I’m moving on in a different way.

Filmmaker: Was there a difference between the response in Angola vs. South Africa?

Van Niekerk: The difference between South Africa and Angola is that South Africa had a reconciliation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. There was a process there where former soldiers could meet their [victims]. But in Angola, that process has not even started. The two armies in Angola, the MPLA and UNITA, are integrated, but no reconciliation has happened. There are no talks or interest in reconciliation. They don’t want to look back. As I was screening the film and had discussions, [the audience] realized the importance of reconciliation and that the different sides of the war have to have a platform to meet and talk. It created a lot of discussion.

Filmmaker: Have the other participants of the film ever been present with you to show a film to a live audience?

Van Niekerk: No, no. But when I was in Johannesburg for the Tri Contintental Human Rights Festival, I went to see Mario who lives in a Bushmen’s settlement in Bloemfontein, in the middle of South African countryside. Mario is like the spokesman for the Bushmen, who were dumped out in the sticks by the South African Defense Force after the war in 1994. There were 5-6,000 veterans and their families in their community, and I had a special screening at their cultural center. And it was just so amazing. All of these people heard that Mario was working on the film, that he went to Angola, but when they actually saw the film it was such an incredible experience. These outcast Bushmen, San soldiers, saw this whole reconciliation process.

Filmmaker: What kind of response do you anticipate from an American audience?

Filmmaker: What kind of response do you anticipate from an American audience?

Van Niekerk: When I looked at the catalogue and saw all the films and people invited, it looks like I’m the only white person that’s going to be there. (Laughs) It’s like the black film festival in America. And I’m a bit scared, because I’m going to be standing in front of the audience all on my own after the screening, and all of these black Americans are going to go, “Apartheid, you white South African racist! What are you doing here in America?!” I don’t know. I’m sure I’m wrong. I’m really honored that they have chosen My Heart of Darkness to be in competition at this amazing Pan African Film Festival. So I’m looking forward to it. And I’m always shit scared when I’m standing in front of an audience. But I think it’s going to be interesting to see the response of black Americans. What do you think?

Filmmaker: I think that American audiences will relate to the experience of war trauma. It’s certainly relevant, with more foreign wars producing more returning soldiers. And I think that the film’s emotional approach will serve audiences well. There are a lot of films about PTSD and war trauma, but few of them match the emotional turmoil of what I imagine that represents. Is this your first time in the United States?

Van Niekerk: Yes it is. I remember when I arrived in Sweden—I went into exile in 1985—I met a black American who was also in exile in Stockholm. And he actually did national service. It was just after Vietnam. When I met black South Africans in Sweden, they were so critical when they saw me as a white, South African, they thought I was an Apartheid, racist Afrikaner. But obviously when they got to know me, and the reason why I left, they could relate to my story. But this black American thought my story was amazing. We got along very well. “Great, Marius! You fought in the war and you turned your back against it!” I’m thinking of that experience I had with this black American veteran in Sweden. I think American veterans are going to relate to this story very much. And hopefully, they will relate to the anti-war side of it. Because a lot of Americans go to war today. I think it’s amazing that boys still go and fight. I would think that seeing the causes of the war, especially in America—veterans coming back fucked up and traumatized—there would be a stronger movement against the military in America. But there hasn’t been.

Filmmaker: How would you like the film to function, not just for veterans but for uninitiated viewers?

Van Niekerk: Obviously, it’s an anti-war film. It’s a film about reconciliation. The reason why I went on this journey and actually did it myself was I believe true reconciliation can only happen when you physically try to repair the damage that you’ve done. There are a lot of Vietnam veterans who are actively working today in Vietnam on various projects. A lot of veterans went back and tried to find forgiveness and peace in the same way I did. And I hope that that message can come across—that if you’ve participated in a war, or if you’ve done something that you feel guilty about, the best healing, I think, is honestly working to repair the damage you’ve done. Which is a very importance message. Because history mustn’t repeat itself. People go to war and don’t seem to learn from it. In Angola, all the soldiers that fought have nothing, they’re completely fucked up. They’re completely traumatized. They’re marginalized. And the politicians and all the military leaders are sitting with all the money. They’ve made money out of this war. And that’s the type of message that Patrick says in the film: that there’s no son of any politician or leader that was fighting in the war. That’s my personal message anyway. True reconciliation can only happen if you’re actively working for forgiveness, and for preventing it from ever happening again.