Back to selection

Back to selection

Director Nelson George on The Announcement

I sat down today with my old friend Nelson George to ask about his recent and past projects. We discussed his newly finished film The Announcement, about Magic Johnson 20 years after he made the announcement that he has the HIV virus. And then we worked backwards and discussed Good Hair, Life Support, and George’s path from journalist to filmmaker.

I sat down today with my old friend Nelson George to ask about his recent and past projects. We discussed his newly finished film The Announcement, about Magic Johnson 20 years after he made the announcement that he has the HIV virus. And then we worked backwards and discussed Good Hair, Life Support, and George’s path from journalist to filmmaker.

The Announcement premiered on ESPN this month and continues to air; for upcoming screenings, including one this afternoon, visit the website. George’s documentary Brooklyn Boheme is now available on iTunes.

Filmmaker: Tell me about The Announcement and how you came to direct it?

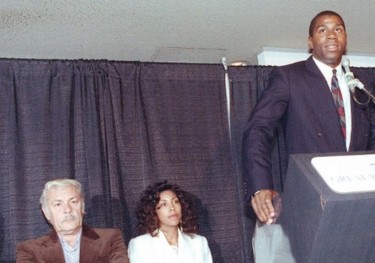

George: I owe it to a guy named Keith Clinkscales, who I’ve known for 20 years. He helped found Vibe back in the day, and he was vice president at ESPN. I think they approached Spike Lee first but he was unavailable. I had done a film on HIV for HBO: Life Support in 2007, and obviously I was a basketball fan, so he reached out to me at the end of August. At that time they hadn’t totally confirmed it. Magic had been approached by many people about doing a 20th anniversary doc tied into his announcement, and he just hadn’t felt comfortable with anyone. I had to go to L.A. on some business so I had a meeting with Lon Rosen, Magic’s partner. He had worked with Magic back when he was with the Lakers. So I got vetted by him, and I assume Magic liked me or liked my reputation. The key thing for the whole thing was to get Magic to agree to an interview. He’d talked about HIV a lot in speeches but he had never sat down and really been questioned about it. More importantly his wife had never done a serious sit-down about the infection. We interviewed Magic Johnson at the L.A. Forum. We shot him literally on the floor, and then we walked around to the locker room, and we also went up to the Forum Club, which was important. The Forum Club was the centerpiece of nightlife, it was almost the Studio 54 of L.A. The Lakers were so popular; every celebrity went to their games, and this was the VIP room. It was also the room where Magic made the announcement. So, we had that room set up as it was that day. I think doing it at The Forum was one of the best creative ideas that we had. It just made it a different thing, and it brought him back to a place that was very special. We were able to get these wonderful shots of him walking up a ramp that leads you into the arena, and you could see that the arena was open – we asked him to walk into the building in silouette and walk back. Being Magic Johnson he immediately gets into the arena-thing and he’s mimicking passes, shooting a fade-away — he just did that on his own. Just beautiful. It was an extraordinary experience. I got my sister in the film, which is an echo of Life Support. The NBA wanted us to talk to Jerry West and a number of the players, but I needed to have someone in it who really represented the other face of HIV, who was not a star and not rich – [someone] to speak to the fact that Magic’s money didn’t keep him alive. He was in amazing health when he contracted it. He did have access to some really good doctors early on, especially in ’91, but there was only AZT back then. The cocktails didn’t come in for a couple for years. So, he and my sister had the same regimen. I wanted it to have that feeling that he’s this big figure, but she represented the everyday person living with the virus. That was really important to have her in there. Chris Rock is a friend of mine, and he added a lot of context in his own way. It was a very big collaboration with NBA Entertainment. They have all the footage of everything and they did an amazing dig to find stuff that I don’t think people have seen before. There’s a point in the film where Magic has the virus, and literally from November through that winter no one would play basketball with him. This guy went from being the most popular player in the game to people saying, “I’m too busy right now, Magic.” People thought they could get HIV through sweat — forget blood, I mean just sweat. There was such fear. He was coming to New York, and Riley said, “Bring your gear.” And we have footage of them working out at Madison Square Garden, which has rarely if ever been seen. Riley is a big emotional part of the story.

I think one of the ironies from a storytelling perspective is that 20 years later Pat Riley and all these macho guys either cried or got very emotional, while Cookie, who is the epicenter of everything, was the calmest, most composed person that we dealt with. She obviously went through the most. Her body was in danger, her baby’s body was in danger, and she has dealt with it. Maybe that’s just women. She just dealt with it. But every time we talked to the men they went back to that day as if it were happening for the first time, which was really interesting.

I think one of the ironies from a storytelling perspective is that 20 years later Pat Riley and all these macho guys either cried or got very emotional, while Cookie, who is the epicenter of everything, was the calmest, most composed person that we dealt with. She obviously went through the most. Her body was in danger, her baby’s body was in danger, and she has dealt with it. Maybe that’s just women. She just dealt with it. But every time we talked to the men they went back to that day as if it were happening for the first time, which was really interesting.

Filmmaker: Who edited the film?

George: A guy named Zak Levitt. He’s an NBA editor. He did another piece called Once Brothers about Drazen Petrovic and Vlade Divac and how the Serbian Croation war affected these two NBA players. He’s a great editor. He knew basketball really well, and he also had a real good human sensibility. He was fantastic to work with.

Filmmaker: Going back, when did you move more into documentary work?

George: What really turned my career around in terms of making documentaries was Good Hair. The through line between Good Hair, The Announcement, and Brooklyn Boheme, there are actually two things that connect all three – one is community – the hairdresser community, which was a world that I knew nothing about when we started. Brooklyn Boheme is about a community that I was very familiar with and in The Announcement, Magic starts off as a basketball jock of the highest order and then becomes a big part of the HIV community, which is a group he never thought he would be a part of. Also, I am really interested in doing post-civil-rights black history. In Good Hair one of the decisions that we made was to not focus on the history of black hair, but to focus on the contemporary history, hair weaves – relaxers do go back, but, I mean, the hair weave in particular is a very contemporary issue. It’s all about the last 15 years or so. We really wanted to make it about contemporary people. I think that’s important. There is a catalogue of Black history documentaries, you know, that Stanley Nelson does so well. But I’m interested in the years since ’75. That’s what Brooklyn Boheme and The Announcement are about – how that history leads to now. I don’t know, I really think there’s a spot that’s open to discuss what the world has been like after the civil rights movement.

Filmmaker:You direct and produce and write — can you speak to wearing different hats?

George: At its core, it’s all storytelling. It all goes back to me being a writer, a journalist. I think that’s really the core of who I am and will always be. That’s how I was trained and everything comes out of that experience. I’ve really had to learn over the last 15 years to be more engaged in visual story telling. That’s been a big challenge. How do you translate your ideas into visual shots? What are the ways in which you can do that? I think people are inherently visual. When you write you basically collaborate with your editor. Film is fun for me ‘cause you have a whole other network of people who are there. I don’t ever feel like I have to have all the answers, and I think that’s really liberating. Also, I felt like fewer people were reading and I wanted to engage a bigger audience. It’s been a process – in the early ’90s I got involved with the wave of black film: I did a Chris Rock movie, I did a movie with Halle Berry. Somehow I had managed to get two movies made but I didn’t feel like I knew what the fuck I was doing. I was at the right place at the right time. So then I went back, I started working with Chris Rock on the Chris Rock Show and that really was a big breakthrough in terms of process. I also started doing short films, I did one that actually did pretty well called To Be A Black Man which Sam Jackson narrated. Even though I had worked on a couple of movies, that was the first time that I actually felt like my voice was in a film. That led me to pitch a project to HBO that became Everyday People, which Jim McKay directed. Everything was an evolution for me and then that led to Life Support. It’s been an evolution – driven by personal stuff too, I mean, Everyday People is about gentrification, and that’s something that I was concerned about then, and obviously now – that film, actually in many ways is very prescient.

Filmmaker:Tell me about Life Support.

George: I had wanted to do a movie on HIV. My sister got it in ’93. I just was too scared. And then one day I sat down with [producer] Shelby Stone in L.A. and I said, “You know I really should so the movie about my sister. I just have to be unafraid.” Still, I punked out for a couple of years, but once I said that, once I said the words, it made perfect sense. Queen Latifah wanted to do it. I knew her from my days as music critic and she respected me and liked me and stuck up for me. Without her I would never had gotten a shot. It was an amazing transformative experience. My sister’s in the movie, as are other women who have the virus (not actors). These women were amazing because they were living with the virus, they were bringing real stuff, but they had a sense of humor and a sense of life about them that was quite extraordinary. I actually have been thinking about trying to gather the women together and interview them about where they are now. When we started the film the model for how you would do HIV intervention was that you would literally do intervention, outreach – give out condoms, go to events, and then Bush changed all the rules. So the kind of stuff that you see in the film – a lot of it doesn’t happen any more. The company that Life Support is based on doesn’t exist any more. The whole game has changed. In fact the numbers in the black community have gone up since then. That’s a project I still think about doing.

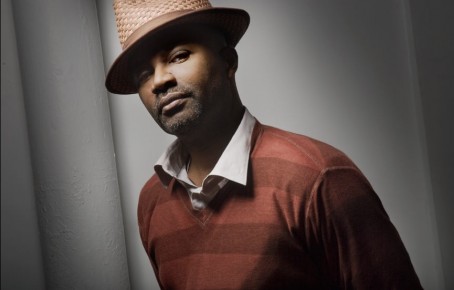

(Nelson George photo, top: Jelena.)