Back to selection

Back to selection

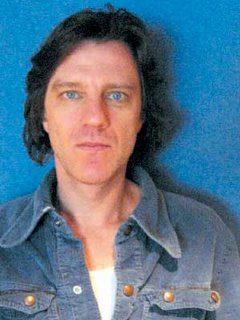

Dancing in the Clouds: Director James Marsh on Man on Wire

James Marsh has wrestled before with subjects — both fictional and real life — whose obsessions have fueled eccentric and, at times, even extreme behavior. In The Burger and the King (1996), based on David Adler‘s book, he chronicled Elvis Presley‘s lifelong habit of compulsive eating. Wisconsin Death Trip (2000), based on the nonfiction book by Michael Lesy, traced the origins of a bizarre strain of murders, suicides and odd happenstances in a small Wisconsin community of the 1890s. And in his debut feature, The King (2005), which Marsh scripted with Milo Addica, he dramatized a story of misguided faith and Oedipal revenge in a born-again Texas family. But Marsh improbably found the story of a lifetime in the person of Philippe Petit, a 24-year-old French wirewalker and street performer who stunned the world on August 7, 1974 when he danced along a cable illegally strung between the two towers of the World Trade Center.

In Man on Wire, which won the Audience Award and the Grand Jury Prize in the World Cinema Documentary competition at Sundance, Marsh brings to life this strangely dazzling and still enthralling episode in the annals of New York City history. Oddly enough, the passage of time has only made this tale more fascinating and emotionally engaging. Petit has told his story before in a detailed memoir, To Reach the Clouds, but in his film Marsh wisely chose to incorporate the recollections of Petite‘s friends and accomplices, some of whom saw their relationships with the daredevil combust after working for years to help him achieve his batty, single-minded, gravity-defying dream. As it cuts between interviews, old Super 8 footage of Petit‘s backyard training and previous feats at Notre Dame and in Australia and ethereal, blow-by-blow recreations of the difficulties his team faced in clambering to the top of the Twin Towers and stringing a wire without being detected, Man on Wire is constructed like a classic heist film on the order of Stanley Kubrick‘s The Killing.

As depicted by Marsh, Petit emerges as an impish and cunning figure, given to curious pronouncements and zesty bon mots, all of which add to his manic, circus-clown appeal. Marsh handles his story respectfully, but a few darker aspects of Petit‘s persona are also apparent. The film‘s showstopper, of course, is the early-morning funambulist “coup” Petit will always be remembered for, and the film‘s grippingly paced buildup to that gorgeously nimble and transcendent moment is part of the reason Man on Wire, which also won an Audience Award at Full Frame, has emerged as a surprise hit this season.

Recently I spoke with Marsh about nostalgia for a bygone era, the challenge of collaborating with Petit, and why some documentary devices drive him over the edge. Magnolia Pictures opens the film July 25.

I actually remember the day in 1974 when Philippe Petit crossed the Twin Towers. As a child in Texas, it suddenly seemed like the world had become a magical place where anything could happen. Isn‘t that amazing? It‘s part of the folklore of New York City, too. It imprinted itself because it‘s a magical transformation of these buildings, a visual transformation. How could someone have had the courage to do this? It lingers in the mind for that reason, I‘m sure.

Man on Wire is certainly about a person, Philippe Petit, but it‘s also about a certain attitude toward life. It is. It‘s about a different era as well. It has those three elements to it. It‘s about someone refusing to acknowledge limits and boundaries, and seeing possibilities as well. It‘s a positive thing: Philippe sees these buildings as a stage to perform on — that‘s all they are to him. They‘re not office buildings; there‘s lots of money-grubbing capitalism going on inside, but he doesn‘t care about that. So it‘s like a satire on the buildings‘ actual function, if you like. This is one reason I like the story so much: It has this subversive element to it. Imagine telling a policeman, “I‘m not coming in — come and get me.” That‘s what he was doing. It‘s incredible.

You‘ve returned to documentary after making your first narrative feature, The King. What was the chronology of this production? The King rendered me unemployable as a filmmaker in this country for one reason or another. The film wasn‘t spectacularly successful, financially, and it riled certain people and critics. It was a kind of cruel film. So there was no way I could make another feature here. That wasn‘t going to happen. I always made documentaries, and I knew about Philippe‘s story. There‘s a children‘s book [The Man Who Walked Between the Towers] that tells it as a fairy tale — which is what it is — that I bought and read to my children. Suddenly I thought, “This is an absolutely amazing story!” And it just happened that a producer I knew, Simon Chinn, was trying to option the rights to Philippe‘s memoir, To Reach the Clouds. I hooked up with Simon and we spent the next months trying to persuade Philippe that I was the right person to make the film. He wasn‘t just about to give it up to anybody. He needed to know that I could pass certain tests.

What do you think convinced him? I like mischievous things. Also I was very open to collaborating with him. I wanted to hear his views, get his input, and he liked that very much. He wanted to collaborate and offer ideas. We didn‘t always see eye to eye, and I‘m not sure he quite knew what I was up to at certain parts of the filmmaking. But nevertheless, our collaboration is at its best in the interview. He wanted to act out the story and run around the room and climb up the walls and hide behind curtains. Well that‘s fine with me! Somebody else wouldn‘t want that, but I thought, “What a great way of shooting an interview.” It gives the film a real energy it never would have had [if he had been] interviewed [the conventional] way. That act defines the film in a certain way. It expresses his personality and I think that‘s what he wanted, too — for it to be his story. But of course, his book is very subjective and idiosyncratic, and I think the film properly opens up other points of view — the conflict and human drama, which was monumental as well. You discover that other people were involved in this story and how passionate they were about doing this. And also how scared some of them were.

How did Petit feel about you interviewing his gang of accomplices and former friends? He wasn‘t that comfortable with some of the people who, as he would say, “betrayed” him. There was a little back-and-forth on that. I desperately wanted to interview the Americans, Alan and David [two helpers who abandoned the project]. Or “Albert” and “Donald.” I have no idea why he calls them that. He was resisting because he felt they didn‘t have any right to be in the film because they hadn‘t seen it through. But [I said] that‘s exactly why. They‘re part of the drama. They were there. David Foreman ends up being a wonderful interview, the musician who smoked pot every day for thirty-odd years and who owns up to being stoned the day he did it. And Alan Welner gives you this wonderful perspective of someone who didn‘t believe in [Petit]. He was a skeptic — a Judas, if you like. [These interviews give the film] another dimension that I think is really important. That‘s the big difference between his book and the film: You‘ve got other voices, you‘ve got these competing narratives, [including the] conflict between him and his best friend. The film could have been quite sentimental, but I like to see it as something more nostalgic. Nostalgia has an ache to it.

To me it was an elegy for a time when there were still real, honest-to-God spectacles to be had in the world and not manufactured, corporate-sponsored “events.” Exactly. Nike is not going to sponsor this. They might now, but it‘d be controlled. It‘s almost like nostalgia for a lost innocence, despite the fact that you get a glimpse of this ugly little scandal that‘s engulfed America with Nixon, who‘s about to resign. And he does resign, the day after Philippe does his walk. So it‘s hardly a less innocent [time]. In some respects, it‘s much more poisonous — the atmosphere — in the city as well. [New York City is] bankrupt, is falling apart, and there‘s a garbage strike. There are shit and rats everywhere. It‘s hardly innocent, but this kind of adventure is possible, probably, because of it.

Speaking of the difference between now and then, and between your film and Philippe‘s memoir, I was fascinated by the suspenseful build of the film. Obviously, the story today takes on darker overtones considering the fate of the Twin Towers. Did that shade your thinking at all when you were staging Man on Wire? It did, but there was a clear choice I made about the structure of the film and how it would tell the story. The story itself is very gripping. It has a kind of classic heist element to it. It‘s very difficult what they do: two teams, one on each tower, avoiding security, with equipment, hiding out until nighttime, going on the roof, all without being noticed. So it offered itself to me very explicitly as a heist film, as a kind of bank robbery without the stealing aspect. It‘s the opposite of that. But of course, I was aware there were analogies, but they were just there. Either you accept them or you don‘t. I‘m aware that these buildings were destroyed in a murderous act of terrorism. I‘m aware that having a bunch of foreigners lurking around the World Trade Center, creating false IDs, hanging out, with a plot against these buildings, has a clear [resonance]. But that‘s implicit in the story. What I decided to do was not make any of this explicit, because it happened in 1974. There are certain images in the film that I find, and that I think the audience will find, really quite ambivalent and chilling. There‘s a shot of Philippe on the wire with an airplane flying close by to him. The meaning of that image we‘re going to reinterpret to some extent, but what it‘s showing you is the scale of what he did and where he is. And why censor yourself? Why filter things? I think it was right not to burden the film with the ugly spectacle of 9/11, but of course I know everyone who sees the film is very aware of it. You kind of trust the audience to complete the film for themselves on that level.

In a way, I thought of Annie Allix, Philippe‘s girlfriend, as a proxy for the audience. That‘s a brilliant observation. I see her that way, too. She‘s introduced as someone who falls in love with Philippe.

She‘s “harpooned” by him. Yes. She‘s a wonderful, elegant, classy, smart French woman. But you‘re right, you enter your view of his character through someone who is very fond of him but is not in any way immune to his faults. She accepts them and she‘s very forgiving of them, but you also see that he rejects her at one point. He goes back to New York and leaves her behind and she‘s very upset about that. She‘s abandoned twice in the film. Emotionally, there‘s a love story in the film. It plays out subtly, but it‘s there.

It‘s also quite poignant in the case of Jean-Louis Blondeau. Yeah, his closest friend, his principal collaborator. And that‘s a distinction worth making. You could make this film in a very sentimental way, but real life isn‘t like that. It‘s ugly and messy, and it doesn‘t neatly resolve itself. Therefore, you have to deal with the consequences of human relationships, which for me are the most important elements of the story. The coda of the film is bittersweet if not, in fact, quite uncomfortable.

Especially since, at one point, Philippe says to Annie, “I need to be a castaway on the desert island of my dreams.” That‘s a classically narcissistic sentiment. [laughs] Yeah. Absolutely. Of course, his first celebration of his own achievement is to go and have wild sex with a woman who offers herself to him [while] his beautiful, loyal girlfriend is waiting to see him. Therein lies the end of the film, if you like. It kicks off from there.

A friend of mine worked on the set constructions for this film, building the rooftop of the World Trade Center, and he said it was a massive operation. Yeah, it was. It doesn‘t look like it onscreen.

What did that production design entail? Basically, we spent a lot of time going around to buildings in the city to see if we could find something that had parallel roofs and gave you a sense of height, and nothing really did. We were shooting at night anyway, so we were not going to see much. And then I [said], how do I do these reconstructions in a thoughtful and progressive way? I thought, “Okay, it‘s like they‘ve gone to the moon or something.” So the reconstructions get less and less realistic the more they go into forbidden territory. By the end, it‘s a very subjective environment, and I hope it works.

Speaking of such effects, a lot of documentary filmmakers, like Errol Morris and Michael Moore, have been criticized for the recreations in their films, though they obviously serve very different purposes. And they have different intentions, of course, too.

What are your thoughts on recreations? First, there is obviously a distinction between documentary and fiction. With documentary, you have to represent something that is truthful — dramatically truthful as well as literally truthful. And in this case, with Man on Wire, if you‘re dealing with a story that is virtually unbelievable, you have to show it, you have to see it to believe it. I don‘t have any big issues with using recreations or any filmmaking technique that can emotionally convey the story and show you what you‘re hearing. I do have one or two reservations about Errol Morris‘s most recent film [Standard Operating Procedure] on that level. In [Alex Gibney‘s] Taxi to the Dark Side, I accepted [recreations] as the best way of telling the story. I saw that they were necessary and I think they were handled very well. Whereas [with] Errol Morris‘s film, I thought the aesthetic choices were wrong, for me as a person who has read and endured a lot of this stuff already. I didn‘t learn anything — I unlearned something. I felt there was a barrier being created aesthetically between me and what I should understand. But generally speaking, I‘m not a purist. The arguments are so well-rehearsed now: Every film is edited, choices are being made, things are being left out and [put] in. [With Man on Wire] I wanted to make a big-screen kind of movie out of [the Petit] story using whatever resources I had, whether they were the big music of Michael Nyman or the reconstructions that are both playful and comedic. And the thing about the reconstructions in Man on Wire is they don‘t pretend to be archival. I don‘t think you‘re particularly confused as to what‘s what, and if you are, then that‘s kind of good. [laughs] Nonetheless, I think there‘s a blend of elements in the film and I‘m pushing each one of them as far as they can go to make what I think is a monumental story as big as it can be.

Nyman‘s score is such a crucial texture in the film, and his titles — “The Disposition of Linen” — are so odd. Did he write any specific music for you? The idea [of using Nyman] actually came from watching Philippe rehearsing on his wire in his backyard. He would rehearse to a whole load of musical textures, one of which was [Nyman‘s] memorial theme from Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, the Peter Greenaway movie. But we couldn‘t afford to pay a composer like Nyman the kind of money he would want to do an original score. Another [director] friend, Gina Kim, had just worked with Michael [on Never Forever], so she brokered a meeting between us in New York. He said, “I can‘t do a score because I don‘t have the time and we don‘t have the resources for it. But why don‘t you look at what I‘ve done in the past? Here‘s my whole back catalogue. Rummage around, I own all the rights to this — you can use what you want.” Then he came and had suggestions and we did some editing and he did a few versions for us. He became a collaborator. But you‘re right, it‘s a very distinctive musical choice, and I think it does give it an identity, even though some of the pieces are familiar to people from other films. But I think we own them for the purposes of Man on Wire.

I don‘t know how many hundreds of times I‘ve heard those two Eric Satie tunes, but my heart was in my throat when Philippe steps on the wire and that music comes up. It‘s beautiful music, but it has something of the flavor [of] a commercial because it‘s been so used. But again, that‘s Philippe — the music he heard in his head was Satie. He‘s French and Satie is French and is a wonderful, mischievous composer.

An eccentric. Yes. An eccentric. We used the “Gnossienne No. 1” as well as the “Gymnopédie,” which everyone knows, but I felt that Philippe‘s walk was big enough and grand enough to claim this music for itself. And if it‘s familiar, then so what? It‘s ours now. Philippe is equal to it.

The power of that sequence also, I realized in hindsight, was because you used the only source material available: still photos. Yet there was something more poetic and powerful about those stills than a moving image perhaps could have captured. Those are moments of time that have been caught. The whole thing is like a dream, if you think about it. There were film cameras up on the roof and the person who was supposed to shoot [the walk] was Jean-Louis, but he couldn‘t because he was so exhausted. So that was the reason why there was no film, even though there was quite organized footage ahead of that. But I went back to a film called La Jetée because, as you know, it tells this intellectually and morally rich science-fiction story by using what appears to be found stills, and they have enormous power. The trick is that [the director Chris] Marker lets you look at those stills for longer than he really should, and [this choice] brings something [new] to the still itself. I think that‘s what we tried to do with the still sequence in Man on Wire. We edited it in one late-night session, one short burst of energy, and pretty much left it as it was.

You‘d previously thought of Chris Marker when you were working on Wisconsin Death Trip. Exactly. La Jetée was such an unusual film. It was really important to the way stills are used in Wisconsin Death Trip. That film was built around images from the last decade of the 19th century, very striking long-exposure, glass-plate negatives. I used stills in that film to tell complicated stories, again allowing them to have unusually long times onscreen. Not that kind of Ken Burns approach, which I don‘t like at all, where you play fiddle music behind the stills, and you kind of revere them, worship them. That‘s something I find cloying and irritating. I had this big aversion to Ken Burns at the time [laughs]. I couldn‘t figure out why he‘d been so sanctified by the prevailing culture. But La Jetée and [Dziga Vertov‘s] The Man With a Movie Camera made Wisconsin Death Trip possible, because what I was trying to do was unusual, and both those films separately showed that you could be really expressive with imagery.

Philippe says at one point that he believed that the Twin Towers had been built for him to walk across. I don‘t doubt it! [laughs] I think he does believe that. And he‘s half right. He‘s a wirewalker, he‘s looking for high-up stages, and then they build the highest buildings in the world at the time, which are crying out for it.

In all your time together, did Philippe ever offer to teach you wirewalking? No, and I never asked him. That was the last thing I wanted to do. I suffer from vertigo and have absolutely no desire, although I have come to an appreciation of it as both a mental and physical discipline. But, you know, it‘s certainly not for me!