Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions with North Sea Texas Director Bavo Defurne

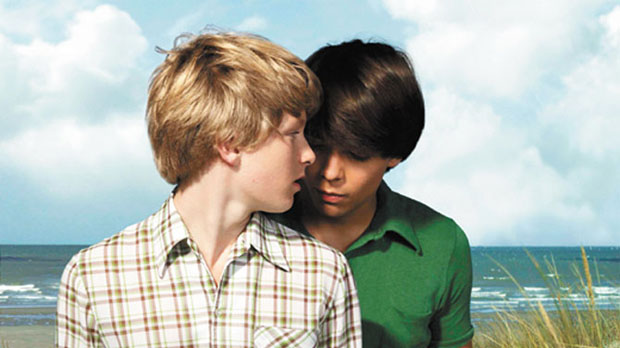

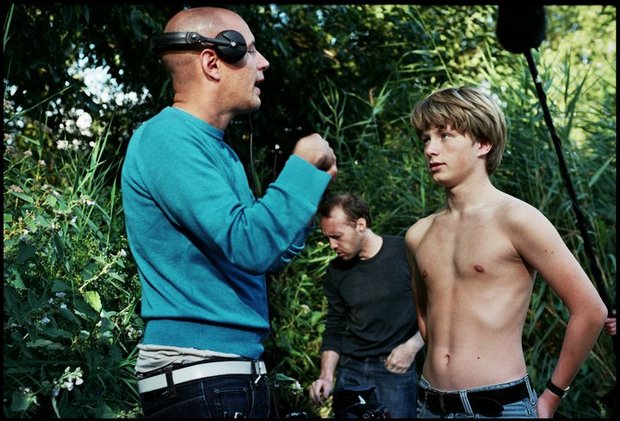

The most striking thing about North Sea Texas is the handsome precision of its aesthetic, which, from the windswept beaches of its coastal setting to the ’70s duds that match home décor, comes close to endowing the film with a magical-realist vibe. A native Belgian and graduate of a Brussels art school, writer/director Bavo Defurne isn’t interested in being a fly on the wall. From a portfolio of ethereal photography to a handful of short films (including Campfire, which gobbled up praise as it cruised the international festival circuit), Defurne has an affinity not for the affected, but for the just north of actual, beautifying his subject matter without robbing it of its weight. In North Sea Texas, his feature debut, Defurne adapts a tale originally told by Flemish author André Sollie, about two boys, Pim (Jelle Florizoone) and Gino (Mathias Vergels), who share a closeted romance. A born outsider doomed to construct his own happiness, Pim is far more ready to embrace the relationship than Gino, and his longing ripples through the film, thematically and visually.

Speaking via Skype from his hometown of Ostend, the deceptively idyllic locale where North Sea Texas was shot, Defurne drops all apparent pretense and speaks plainly about his art, which he hopes reflects the world while also parting its frequent storm clouds.

Filmmaker: There have been a lot of young-adult novels gaining attention recently, particularly in regard to film adaptations, but we haven’t seen any quite like André Sollie’s This Is Everlasting, on which your movie is based. What made you think the story would translate well to the screen?

Defurne: Well, I actually may have chosen something a little too easy [laughs] because the story is very visual. Sollie is a visual artist and a poet even more than a writer. This was his first novel. He wrote a lot of poems and made a lot of drawings. I think he was 60 years old when he wrote this book. And it’s very visual, and very poetic. That’s what I liked about it. The novel really has very few expressions of inner thoughts and emotions; most of the things he writes about are situations and beautiful, visual moments. So it was kind of easy for me. And I liked how it had a positive take on its subject. I didn’t want to make something with a Brokeback Mountain ending. We live in a country [Belgium] where a man can marry a man and a woman can marry a woman. In the way that this story is told, I think it can reflect positive things about our society.

Filmmaker: The film was shot in your hometown of Ostend, and the landscape is very integral to the mood and look of the film. Was there something specific about the environment that made you know it’d be a good fit for the story?

Defurne: Yes. We’re here in a little beach town. I actually went away and lived in the big city and didn’t like it, so I came back to my hometown. There are so many personal reasons [for the shooting location], but, essentially, when I make a movie, I want to make it—how can I say—a little bit romantic. What happens to these characters is quite hard and difficult sometimes, and there’s a lot of loneliness and rejection. I didn’t want to make a gritty, sad, gray movie. I didn’t want to make it realistic. So I thought that it needed a beautiful natural setting. And, to be very honest with you, [Ostend] is a city with cars, and ugly houses, and a lot of tourists. So it’s not really as pretty as it looks. We had to cheat to make it look so pretty. Why did I want to make it so pretty? To make it easier to digest for audiences, I guess. There a lot of mixed feelings in the film, and negative feelings too. [Pim] doesn’t have a father, [Gino] doesn’t have a father, there’s death in the movie, people going away, people getting upset. And I didn’t want to make it even more negative. I really wanted to make a movie I would want to see, not something that chases people away.

Filmmaker: In general, from your short film Campfire to your photography, nature is just as much a recurring theme as gay relationships. In North Sea Texas, you often overlap the themes, cutting to waving grasses and windy beaches in especially intimate moments. From your perspective, how do these elements relate?

Defurne: Well, I try to make movies as visual as possible. I’m really into silent movies. When I lived in Brussels, there was a film museum that showed silent movies daily, with a guy playing piano. My ideal movie would be one that, even without subtitles, even if it were in Dutch or Chinese, someone who didn’t understand the language would still understand what the movie was about. So that means a lot of visual storytelling, and there are some things you can’t speak about, especially in stories I tell. There are a lot of things people can’t really say, or they’re too shy, or there’s no one to talk to. So I have to express this, and I think I use nature as a means to express things that people can’t, or won’t, talk about. So, say, the lonely gay teenager, who’s sad—who should he talk to? Or the lonely, straight teenage girl—same story, same emotions. She’s sad and she’s lonely, so she goes into nature, into the dunes, and talks to the clouds. She talks to the wind. I think it’s something adolescents do. I’m not an adolescent anymore, and I’ve found people I can talk to, so I don’t go into the dunes to speak to the clouds. But I think it’s typical of the loneliness of teenagers to go off into nature.

Filmmaker: There’s also an artistic theme that runs through the film, as Pim is always drawing and he’s labeled a dreamer—a visionary. I’m assuming there’s some identification there between filmmaker and protagonist.

Defurne: Hmm…a little bit. Well, it all comes from the book and it’s very true to the book. If it were autobiographical, it would be about the author, and not about me. But, still, we’re kind of sister souls, or brother souls, if you will, the writer and me. We share a lot of things that we love and emotions too. I read his book and wrote a letter to him, and he had seen my short films. Of course there’s some connection between me and Pim. Sollie makes drawings all the time. I don’t really make drawings all the time, but I am, in many ways, a dreamer, and I like that. Pim is a boy who makes the world more beautiful, and I think that’s one of his strategies to cope with the world. And I think that’s part of your job as an artist—to make the world comprehensible, or make the world a better place, by showing something beautiful. Am I a dreamer? I don’t know. But the world can be rainy, and dark, and dull, and the movies I make are a bit like fairy tales, in the sense that they’re not realistic, but what they talk about are very true relationships and feelings between people.

Filmmaker: Aside from the film’s very strong compositions and picturesque setting, there’s something consummately cinematic about North Sea Texas, as it’s dreamily depicting a boy and his escapism, and it could also serve as an escape for a boy like Pim in the real world. Was this something you thought about when you were making the movie?

Defurne: Well, I think there may be lot of Pims in the audience. The film’s not really meant to have some really strong message, but, intuitively, I really liked making it and I hope people connect to it. One of the most beautiful compliments I’ve had about the movie was during its premiere in London. A guy in his thirties came to me and said that the first time he fell in love like Pim was when he was 27, and he was happy that, in this film, he was shown what his youth could have been. So he was happy to have seen himself in a hypothetical way. Maybe that’s what I’ve tried to do with this movie—show a possible way that someone’s youth could have been. There was a guy at the Palm Springs International Film Festival who said that being in love in the 1940s was just the same as it is in [North Sea Texas]. So an American guy who must be over 70 recognized himself in the movie, and I think that’s the most valuable thing. I’m really very happy that there are people out there in the audience, in China, Poland, or the USA, from 16 to 66, who recognize something of who they are. That’s what excites me as a filmmaker.