Back to selection

Back to selection

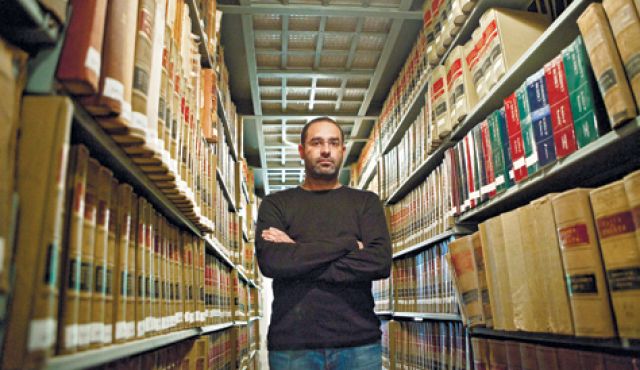

Ra’anan Alexandrowicz on The Law in These Parts

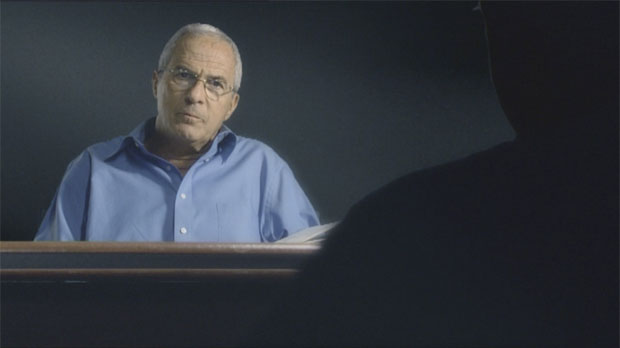

Ra’anan Alexandrowicz’s The Law in These Parts sheds new light on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from an unexpected perspective. Interviewing nine military judges, the director explores how Israel created a new legal system to control the Gaza Strip and West Bank after occupying them in 1967. At first, the state may have begun with the understandable desire to defend itself from violence, but its justifications quickly became self-serving. In one of the film’s most memorable examples, a woman was sentenced to a year and a half in jail for giving a “terrorist” bread. The film consists of stylized interviews with the judges, shot on a set with a green screen, which is sometimes used to project archival footage of Palestinian uprisings. Alexandrowicz covers the history of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and the methods used by military law the country to govern a people who became stateless for decades, depicted from the perspective of the men who prosecuted Palestinians. His style is self-conscious, and points out his own gaps and moments of dishonesty. The Law in These Parts resembles Errol Morris’ epic interrogation of Robert McNamara in The Fog of War at times, but Alexandrowicz is far feistier interviewer. Often, one expects his subjects to walk out. Filmmaker spoke to him on the eve of his film’s New York opening.

Filmmaker: Your interview style is quite contentious. Your interviews seem very tense. Were they as difficult to conduct as they appear?

Alexandrowicz: They were not easy to conduct. I’m not a legal professional. I was struggling to understand material with which I was dealing and interviewing people whose profession it is to work with it. I was working on a set, not people’s living room or office. So it wasn’t an easy situation. What took over is that I spent a lot of time studying this material, in detail. On one hand, I wanted to continue asking questions when I felt there was still something to talk about. On the other hand, I didn’t want to create an atmosphere where people wouldn’t want to talk. Creating that balance took some effort. At certain points, some of the interviewees were unhappy.

Filmmaker: Why did you decide to begin the film with the construction of its set?

Alexandrowicz: I wanted to focus not only on the subject I was documenting but on the documentation itself. This is something that came up during the editing of the film. I had already been working on the storytelling for a while and realized I needed to intervene more than I did. It was originally supposed to be one long interview, in a question and answer format. The audience was missing a lot of context and needed to be helped to decipher the subtext. I started thinking about storytelling devices. Because of these thoughts, I realized that I’d like to make the storytelling very apparent. I decided that there’s a strong parallel between making apparent the subjectivity of the documentary and the subjectivity of the law. By showing both, I could actually help the audience understand a lot of issues by exposing how law is pursued in the occupation.

Filmmaker: Has the film been criticized for not including interviews with Palestinians?

Alexandrowicz: Yes, it has been. The decision to tell the film from…I wouldn’t necessarily say from our side, but from our words was one of my basic directorial decisions. It had to do with many reasons, having to do with me being an Israeli filmmaker, films I made before which documented the Palestinian voice and what I felt about that afterwards, and the main audience I’m trying to reach, which is mainstream Israeli society. I thought it would be the most effective way to reach that audience. Now that the film is reaching other audiences, such as academics, I realize that this decision had a greater effect than I expected.

Filmmaker: How was the film received in Israel?

Alexandrowicz: Naturally, there was a mixed reaction. It’s been screened nearly 200 times in public in Israel. For a documentary, that’s quite a lot. Half of them were with discussions with different kinds of audiences. If I can choose what’s most important to me, for many Israelis, such as bureaucrats or teachers, the film becomes a mirror of what happens to us when we bring our education and ethics to a system with an agenda that’s not necessarily ours. By our complicity, we have to forward that agenda. The film raises a mirror to this human situation. Many Israelis are seeing the film and maybe because it just uses the words of Israelis, it makes them see into the mirror. That’s my feeling from their reaction.

Filmmaker: Has it also played to Arab audiences?

Alexandrowicz: There have been a few, not many. We did invest in creating an Arabic-subtitled version. Our resources are limited, so I’m focusing on Israel. But once in a while, there’s a screening in the West Bank or a Palestinian audience within Israel. I thought the fact that I decided to tell the story just through the voices of Israeli legal officers would make a Palestinian audience not want to engage with it. There are many Palestinians who’ve had demeaning experiences with the Israeli legal system, so it’s not just a subject for a film to them. What I did see at these screenings was the Palestinian audience was a mirror of the Israeli audience. They might laugh where an Israeli audience is silent and shocked. It was an inverted reception. From the discussions after the film, there are definitely Palestinians who find it engaging.

Filmmaker: The sections of the film I found most engaging were the ones dealing with torture. They come near the end of the film. Were your interviews structured so that you knew in advance you’d be addressing that point then?

Alexandrowicz: This is the kind of film where you think a lot about the interview’s structure. It’s not just questions and answers, but a dynamic scene going on between the people I’m interviewing. I left certain subjects aside and tried to approach them in a more provocative way. I knew the subject might end the interview if torture came up. That’s why I brought it up near the end.

Filmmaker: Have any of the people you interviewed reacted to the film publicly?

Alexandrowicz: First of all, I think it’s important to say that half of them are very unhappy with the result. It was not a surprise to me that this would be the reaction. These people told me or other people their reaction, but they haven’t attacked the film publicly. Other people either feel that the film is good or have mixed feelings about it. Some have agreed to participate in Q&A sessions afterwards. They have qualms about its perspective or what it doesn’t cover, like the idea that justice isn’t the primary value when you’re a military lawyer, or even the juxtaposition of their words with someone else’s words that they don’t agree with. On the other hand, an important moment for me was at a public event when one of the protagonists said the film had an objective he wasn’t aware of when he gave the interview and it’s something he wasn’t happy with, but he can understand why my action was necessary in order to open people’s eyes.