Back to selection

Back to selection

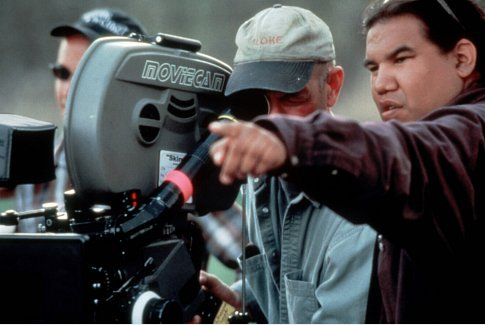

The Work is the Reward: Chris Eyre on Hide Away

It’s hard to believe it’s been nearly 15 years since filmmaker Chris Eyre burst onto the indie scene with 1998’s Smoke Signals, based on a short story by fellow Native American Sherman Alexie, who also wrote the screenplay, and starring Native Canadian Gary Farmer (probably best known for Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man). Since then the Portland homeboy has seamlessly shifted from the big screen, to PBS fare, to franchise TV and back again, most recently with Hide Away, an existential drama featuring Josh Lucas and James Cromwell. Earlier this year, Chris was tapped for an entirely different gig, chairing the Moving Image Arts Department at the Santa Fe University of Art and Design, which is where I first met him when I arrived in town as the new director of programming for the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival. (Full disclosure: the second time I ran into Chris it was at Gary Farmer’s house party where the host and his band regaled us guests with an impromptu jam session in the garage. Now that’s what I call a warm southwest welcome!)

Filmmaker: So your latest film Hide Away is a pretty white story. Personally, I’m all for filmmakers jumping out of defined boxes – Spike Lee and Gus Van Sant are indie auteurs first, black and gay directors, respectively, down the line – but do you feel any backlash from Native Americans dismayed at seeing Josh Lucas and James Cromwell starring in the latest Chris Eyre flick?

Eyre: [laughs] Yes, this is my “white period!” Although it probably started with the network TV I directed a few years ago – Law and Order and Friday Night Lights. So far I haven’t seen any backlash from Native peers or audiences. Ultimately, we all know it’s about “making work” and continuing to make good work as an artist. Which means they are just different “songs,” so to speak. This movie Hide Away is almost dialogue free. I wanted to make a purely visual movie with atmosphere and character. Frame for frame, and story point by point, I love this movie because it’s a departure for me. Whether or not the characters are Native or not wasn’t something I thought about. I just embraced the story and the people in it.

Filmmaker: Also, just looking at the opening credits of the movie I notice a lot of non-Native names. Do you not work with Native Americans in key production roles? If this is correct, why not? (In contrast, Spike Lee certainly practices affirmative action when it comes to his crew. What’s a minority filmmaker’s obligation?)

Eyre: A filmmaker has an obligation to his or her voice, to his or her audience, to the story. That is the barometer. I would love to hire largely Native American crew, and now you can, but it’s not essential. What is essential is that you make the best work you can make with the most talented people you can collaborate with. There is this utopian hope that not only will I someday make the great Native American version of Schindler’s List, but also do it with an all Native American crew. My attitude is not to get stuck in the politics, and to create work whenever you get the opportunity to speak as an artist. The real prize is to produce a body of work. And who wouldn’t want to work with massively talented people from anywhere?

Filmmaker: Hide Away has a very old-fashioned vibe to it, with visual echoes of Knife in the Water. Who were some of your filmmaking influences growing up? I noticed you have books on Scorsese and Ford on the table in your office.

Eyre: Hide Away has actually been described as having a 70s feel to the filmmaking. I was raised on all the typical fair of 70s movies and TV. I love pop culture and Native culture and American culture. Lately I have been revisiting Stanley Kubrick’s work, inspired by a documentary on him that I watched a year ago. He made less than ten films in a very specific and methodical way. He understood story in a very human and powerful way. Each of his films is different, but spoke the same truths about people’s tenacity. I love John Ford’s movies, too, despite the fact that John Ford and John Wayne’s movies together did the most harm to the image of Native people worldwide, second to the Bible, that is. The doorways and windows and vigilantism in The Searchers are beautiful. I love a good western.

Filmmaker: One of the most surprising things for me to have learned about the Native American community is that there really is no such thing. There’s actually a lot of political bickering and animosity between tribes. (I think it was Gary Farmer who reminded me that tribal warfare was always the norm throughout history, and that there are around 600 different tribes throughout North America.) Which made me examine my own preconceived notions – I mean, no one would expect me as a NY Jew to be best buddies with an Israeli. That said, do you think these historical tensions are keeping Native Americans from actively pooling their filmmaking talent and resources together?

Eyre: There is such a thing as a “Native American community,” and sometimes it’s not always harmonious, but it is ours. Just like America is ours. We love them both and contribute to them both, sometimes at the same time. I live in New Mexico, and if Native filmmaking is happening anywhere in this country it is happening here, with many young and talented people that are collaborating. All independent filmmakers are facing the challenge of getting their work seen in wide distribution. We all know today’s challenge isn’t making the movie as much as it is getting the movie seen.

Filmmaker: Finally, what are some of the challenges of being a working filmmaker while simultaneously heading up the film department of a university?

Eyre: [laughs] Good question. Recently, I became the chair of the film department at Santa Fe University and I’m loving it. Thankfully, this university wanted a “working” filmmaker to head its department, and so I am doing just that. Along with my duties to ensure our students get the best film, TV and emerging media education possible, I am still doing my own films such as Hide Away – and next up is a thriller called Dead River. Being busy is the only way to go. I tell my students as they are making their first films, “The work is the reward.”