Back to selection

Back to selection

Social Studies

Leading up to the Oscars on Feb. 22, we will be highlighting the nominated films that have appeared in the magazine or on the Website in the last year. Brandon Harris interviewed The Class co-writer-director Laurent Cantet for our Fall ’08 issue. The Class is nominated for Best Foreign Film.

Starting with 1999’s Human Resources, Laurent Cantet has quickly built an international reputation as France’s most socially engaged narrative filmmaker, crafting films that highlight the ever lingering issues of race and class in both France and, as in the case of his 2006 film Heading South, its former colony of Haiti. With his new film, The Class, Cantet has attained new levels of acclaim and is primed to reach significant worldwide audiences with a timely story of one teacher’s attempt to instruct his multicultural French-language class, many of whom see French identity as something that can never truly belong to them and who live in a culture and language they have little affinity for.

While the film is firmly rooted in the well-worn genre of the classroom drama, the authenticity and immediacy with which Cantet renders this tale allows it to transcend and ultimately redraw the limitations of this familiar setting. Blackboard Jungle, Dangerous Minds or even Half Nelson this is not; Cantet shows us with great specificity and common empathy the everyday challenges and failures of basic secondary education in a multicultural society.

Based on a book by French schoolteacher François Bégaudeau, who plays a version of himself in the film, The Class meditates on an adolescent French-language class in a public school in Paris. As Begaudeau’s teacher slowly loses the good faith and interest of his mostly black Caribbean class over the course of a full year, submitting in a battle of wills to a pair of unruly but sophisticated young girls and a proud, rebellious boy, Soyleymane, Cantet takes us to a place where the children of poorly educated immigrants are too often left behind. As teacher and students march through the complicated grammar and tenses of the French language, the kids’ own cultural roots are largely ignored by a man who has the best of intentions but whose methods may not prove sufficient.

A late edition to the Cannes lineup this year, Cantet walked away with this year’s Palme d’Or and in an unforgettable moment, invited his entire young cast onstage to revel in the honor with him. The film opened this year’s New York Film Festival and will be released by Sony Pictures Classic in December.

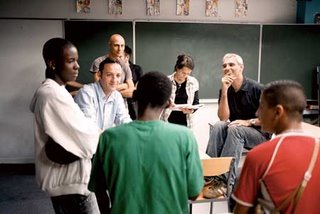

TOP OF PAGE: FRANÇOIS BÉGAUDEAU IN THE CLASS. ABOVE: THE CLASS CO-WRITER-DIRECTOR LAURENT CANTET (RIGHT). PHOTOS BY PIERRE MILON.

TOP OF PAGE: FRANÇOIS BÉGAUDEAU IN THE CLASS. ABOVE: THE CLASS CO-WRITER-DIRECTOR LAURENT CANTET (RIGHT). PHOTOS BY PIERRE MILON.How did you stumble upon François Bégaudeau’s book and when did you decide you wanted to make it into a film? I already wrote the beginning of the script two years before reading François’s book. It was taking place in a school just like the book and it was telling the story of Souleymane that we kept in the final script. Then I forgot about the project while making my previous film, Heading South. The day Heading South was released in France, I went in a radio studio and François was there to present a book of his that was released on the same day. He talked about his book and read some parts of it and I realized that it was really connected to my next project, first because it was based within the walls of the school and that François could give me a lot of documentary material that I wouldn’t be able to get by myself even if I planned to stay in classes to see how they work. François had been a teacher for 10 years before writing this book so he could bring me into the classroom much better than I could have done without that. I also like his character, the way he is in front of his classroom, the way he talks to his children. The way he is also trying to stimulate their minds, to show them that their way of thinking is too short and trying to get them to go a little bit further — that really interested me. Also, the way he is not afraid of fighting with the students. He’s not just trying to make things smooth, he’s taking the risk to confront them and that’s something I like. I think it’s a way to show the children that he cares. He considers them.

Other than the Souleymane story thread, were there other things you took from the book? Souleymane was not in the book. That’s what I wrote before. What we wanted was to chronicle the life of this class and then in this class we identify a few characters that will take the fiction on their shoulders. Souleymane was one of them. When we met with the children in the workshops the year before shooting we met Esmeralda. The first time I saw her I knew she would be a good [character] for us.

She’s a contrarian. Yes. So we created some characters like that which came out of the class and became important figures in the film, but we never tried to adapt the book. What was important for me was that François was playing the teacher and he knew exactly what I wanted from each scene. Before shooting I went to each student one by one, telling them “When François says that, you will say that. When he will say that, you will answer that. I want you to be like that or like that.” They had some landmarks in the scene. François was in front of them. The children were allowed to improvise in front of him except that I wanted them to include in the improvisation all the sentences I had asked them to say. So they said everything I wanted them to say, but within these improvisational parts that really brought life to the film. That’s why I say it’s not an adaptation because what we kept from the book, these elements, we placed in the structure of this class. That gives them another reality than they have in the book or would have had in another class. We never copied exactly from the book.

So we couldn’t call it an adaptation, but something else? Right, right. Except that we also guide them in the direction we were expecting to go. After the first take, which was very improvised like that, I was speaking with each of them, telling them I wanted them to keep one thing, not the rest. “This thing that you said was interesting — can you say it again?” And so they were replaying what they gave me in improvisation in the first take. They had the same energy in the seventh take and the first one. I could mix the first take and the last one. It’s exactly the same energy and just as natural.

How were you able to make these children and non-actors comfortable with this new circumstance of making a film? How do you create an environment where they can open up? We worked a lot before shooting. We had a workshop during the entire school year. Every Wednesday we used to meet for three or four hours, improvising on situations, just to confirm that what we were writing on our side was not too far from what they could do or think. Then we talked a lot; I listened to them very carefully. I think they really understood that the film was trying to respect them, and they trusted me. They were very involved in the creation of the film; they worked from the very beginning of the writing. They felt proud of being in the center of the process, proud of being listened to by me, and also they are not impressed at all by the camera, by the technical apparatus and all that. They are used to it. I never had to tell them not to watch the camera. The first day we were shooting, they came into the classroom, the lights are all over the ceiling, three cameras are in front of them, a boom operator standing there, but they just went to their tables and didn’t even take notice of all that stuff. They just improvised like the day before.

What are some of the differences between directing non-actors and someone who is formally trained, professional performer? I don’t think I directed them too much. They were the characters. We built each character with them during the preparation for the film. Even if it’s not them, they are close to what they could feel, and situations they know and have experimented with before. The inspiration comes directly from them. For example, the boy who was playing Souleymane, Franck Keita, is the opposite of Souleymane. He’s a very nice boy, very quiet, very discreet, but we worked a lot before that and he got used to that character and he could make it real. He just became the character whenever we were shooting.

What about Begaudeau? I didn’t direct him much. Except at the end of the film, when he’s losing control. In all the beginning of the film, I didn’t direct him. He was also the double of myself in the scenes. He could help me to drive the children to what we were expecting. He was more thinking, “So who is going to speak now? Is it her, or him?” He was more focused on the organization of a scene. He just behaved like he used to do when he was a teacher.

The film depicts a France that’s at a crossroads culturally. It asks what it means to be French in a multicultural, 21st-century France. Did you learn anything about what that meant to these young people while you were working with them? Do they view their Frenchness differently than you did when you were their age? When I was 15 years old, I was in a little province outside Paris and in our classrooms we were all white, middle-class children. My children are now in junior high school in the suburbs of Paris and I think they are much more open to all components of society just because they are spending time with people coming from everywhere, dealing with them and having the same recreations. I think it’s very important for them. It helps them to have an open mind. After that, it’s not a problem for the children, but it can be a problem for the adults. The adults create problems around them.

How? By being afraid of that diversity and by stigmatizing this group of young people. It’s not easy to be young in France, or all over the world, I think. Everybody is a little bit afraid of your reaction. Thinking that you are dangerous. Everybody is afraid of those children, especially if they are not white, if they are not speaking correct French. I think one of the reasons to make the film was to try and watch this multicultural, multiracial group from different social backgrounds and just show that they are not only thinking of burning cars and insulting adults, but that they are just children trying to understand the world, find a place in the world, find a place in our society. For example, when Esmeralda says once that she’s not proud to be French, I can understand her. If you want to be proud or to feel a part of a community, you have to be sure that this community desires for you to be a part of it, and I’m sure that she doesn’t feel that way.

So this film is then in ways informed by the unrest and riots of 2005? It was not that important. I was in the States at that time. I was watching TV in Los Angeles and I thought it was the revolution in France, and I came back and it was not that…

It was overblown? Yes, sure, but I think it’s important to take the question into account if you don’t want to have problems with those children.

How do you think a western country like France does that given the fact that they have classrooms like this, with people of all hues and colors, which is a direct result of their imperialist ambitions of centuries before? Not only that. The country is richer than a lot of others. A lot of people…

Gravitate toward those countries seeking opportunity and a better life. I’m not trying to say that colonialism is not part of it. But it’s not only that.

It’s much more complex than that. But I’m saying, given all those historical factors, how does a 21st-century France include these people in a way that makes them feel welcome? I don’t have any answer to that question, if I would have…

You would have run against Sarkozy. [laughs] I think what the film says is that it’s important to look at them, to take them into account, and that they feel themselves to be unconsidered and neglected.

One of the wonderful things about the film is that you empathize with these children and their teacher and the system in which they find themselves all entangled, which is clearly flawed, but which has good intentions. It seems that these kids find themselves ill prepared to accept some of the things François’s character is telling them. Even if he found a way to communicate these things to them, given their immigrant experience and that they aren’t inheriting French culture at home, how would they find a way to process it in the classroom? What the film says is that no one is guilty of the situation. I think teachers, some teachers, really try to work like François, to try to give that space to dialogue, and that for me is the only way to start to make them feel like they exist in this community. The only guilt is the scholarship system, which is built on selection. In France we have a very strong sense of what our culture is. Classical culture has the highest value in the eyes of most people, but it’s somewhat heavy for such young kids.

And yet a young woman like Esmeralda’s character in the film is ultimately revealed to be someone who is versed in that culture, even though her teacher is ignorant of that fact. The scene about her reading The Republic was not invented; it was something that one of the students told Begaudeau when he was a teacher. It was almost too perfect for the film. I was really hesitant about using it. So when I was still hesitating about it, I talked to Esmeralda and we gave her a few elements to explain to her who Plato was. The way she said it again in the scene afterwards proved that she not only had understood perfectly what we had explained to her but that she would have been able to read it and learn something from the book. In the film, the reason she read Plato was because it was something her sister showed her and not the teacher. But on the other hand, maybe she wouldn’t have been interested in that book if it wasn’t for the school context to contradict so it’s also something she can be grateful to the school for. It’s important to note here that the vision of school as a sanctuary where children would arrive and leave behind their preoccupations and their cultures just doesn’t work. If schools ignore [students’] experiences out of school, and everything that makes them specific and unique individuals, they will impose on them things the children will not accept. There are still a lot of people who consider school that way, as a place to go and ignore the world.

There are a lot of films that fit into this genre of the classroom drama. I think in many ways your film transcends them. Were any of those films of use to you, with similar themes and milieus, even if just to say, well this has been done I’m going to do it another way? Not really, the only thing I was trying to avoid was to make another Dead Poets Society. [laughs] That teacher was a sort of guru, he knows everything — we wanted to show a teacher with all his weaknesses, who doesn’t know everything, who sometimes makes big mistakes with the way he is talking. It’s the way things really happen in school. If you are a teacher you have to answer very fast, you take risks and you are not a model. There is a film I really like, [Jean Vigo’s] Zero for Conduct, and what helped me by watching this film was this energy in the way the children are speaking.

Your films often have a documentary-like quality to them, but yet also a lyricism. Do you design the films or are they shot complete off the cuff, in a vérité style? Do you have in your mind specific shots you have to get when you step on set? How do you work? I don’t have any storyboards or anything like that. The main part of the mise en scene for me is to find the best system to film the situation we want to show. Each film gives you a different way of building that before you begin shooting. Here it was working with non-professionals, working with children, listening to them. François was playing his own part, he was a teacher, he wrote a book, we adapt the book, he’s playing someone who’s not himself but is basically himself. The main thing I wanted to get was this energy of the discussion between them, so we decided to have three cameras. Since we started with that I was sure that we wouldn’t have to cut and do it again and get a reverse shot. You just film in continuity and they never know who is on camera. They’re playing the whole scene without waiting for the moment when they are going to be filmed. I think that’s what made the difference between this film and my previous film…

Heading South, which is much more controlled… Yes, much more. In fact, when I decided to make this film, it was to come back to the method I used when I made Human Resources and even before in my first short film, which was also a story between students who are preparing a strike in a school. The difference here is I’m shooting in HD video and it allows me to give them the opportunity to improvise even during the shooting. I worked with them on improvisation before the shooting and everything was a little bit more written when we arrived to set. This time it was possible even during the shooting to change everything. I don’t know what my next film will be, but I would like to be sure that I have the freedom to write a script knowing that it’s just a starting point and that it can change. For this script we managed to convince all the financiers for the film that it could change, that we were not sure that the film would be exactly what was written in the script. They accepted it, maybe because the film was not very expensive. I hope I can go on working like that with this freedom.

Would you ever consider making a film here in the States? Is it something you desire? Why not? A few years ago I almost did it. I met some young L.A.-based producers who proposed that I go to New Orleans and make a film about people who had gone through Katrina. The idea was to just go meet people in the streets of New Orleans. I had some stories that were intermingled and that I wanted to include with testimonies from them. In this case, that method was not accepted by the financiers for the project. They wanted something way more scripted. It’s in France with this film that I completely gained this freedom to choose how to work, so this is why I want to continue working there. But it’s true that I’m really interested in American literature and mythology. I’d love to make a film in New York. One day.