Back to selection

Back to selection

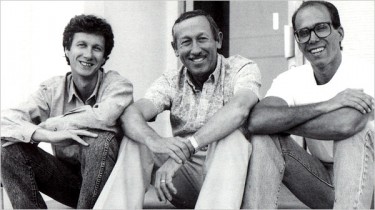

Don Hahn, Peter Schneider on Waking Sleeping Beauty

As filmmakers, we are genetically programmed to look to the future. The next script, the next movie, the next deal. After all, the films — on DVD, on hard drives, in canisters stacked in our closets — are their own memories.

Except, of course, that a film only tells part of the story. They are the ends of their tales, not the beginnings, and they only tell their own stories, and not the dramas of their making. If at all, those stories that circle around a film are only sometimes relayed in magazine profiles or in books written by people who have had little connection to the times and people they chronicle.

With Waking Sleeping Beauty, director Don Hahn and producer Peter Schneider accomplished what every filmmaker must dream of at one point in their career: revisiting their earlier successes — the revitalization of Disney animation — and entering their own version of the story in the historical record. The two were part of Disney’s epic animation run in 1980s and ’90s, a time whose industry coverage was dominated by boardroom dramas involving Disney CEO Michael Eisner, studio chairman Jeffery Katzenberg, board member and head of animation department Roy Disney, and President and COO Frank Wells. Schneider was President of Feature Animation and Don Hahn was a producer of the two biggest hits during this time: Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King. As Schneider notes, it was a well documented era, most notably by James Stewart in his Disney War, but the creative energies that powered its animation department were never extensively detailed. Mixing voiceover interview, archival footage and, most notably, recently discovered home movie footage shot by Randy Cartwright and John Lassiter, Hahn and Schneider walk us through these years, balancing the requisite executive drama with the story of the hundreds of creative workers who include Tim Burton, Lassiter, Bob Zemeckis and, memorably, the late Howard Ashman, whose lyrics to The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast were a major part of the startling and successful reinvention these films represented.

Premiering last year at Telluride and the Toronto Film Festival, Waking Sleeping Beauty has been traveling the doc festival rounds before opening today in limited release by Disney. I spoke with Schneider and Hahn separately by phone for this edited interview.

Filmmaker: Peter and Don, what motivated you to make this film?

Schneider: I was at Disney for 18 years, and after I left in 2001 I felt that there was a story there that no one had captured. It was well written about period of time — there was the James Stewart book and all the drama covered in the mainstream press. But no one, I thought, had captured the essence of the emotional story of what happened.

Hahn: For me, it grew out of talks with Ed Catmull, who is today’s president of Disney animation. I was saying to him, “It’s really important that we tell this story because we’re going to forget it. Don’t you wish there was a documentary about Walt Disney and his colleagues? Let’s preserve it now while these stories are still intact, when people are still alive.”

Schneider: It has now been 25 years since Michael, Frank and Roy took over company, and 20 years since Beauty and the Beast opened. And, of course, Roy Disney has just passed. We did a screening at the Frank Wells building. Everybody knows who Frank Wells was, right? Well, one woman said no. I said, “You work in the Frank Wells building. Did you ever stop and say to yourself, ‘Who is Frank Wells?’” He was an important figure, so I also did it for that reason. I wanted to set the record straight.

Filmmaker: What specifically was it that these other accounts of this era failed to capture?

Schneider: What people failed to capture amidst all the drama was the joy that exists while you are making a creative project. I wanted to capture the extraordinary joy of that period of time as well as the personal drama. It took the entire team to make these movies successful. It wasn’t just one individual, two individuals — it took a collective group of people working in a unique manner. It always gets put out there that Jeffery did this, or that Michael did that, but I wanted to show the inspirational teamwork. That was my motivation.

Filmmaker: As subjects, why did you decide to make the film yourselves with Don directing?

Hahn: Peter wanted to make the film for a long time. I was reluctant at first. I knew that the film would have to draw from so many inside sources, and that it would need [as a director] someone who could access all of that [history]. In the end I decided to jump in and direct it myself. If we hired someone else I knew I would just be pointing them in the direction of film clips and stills.

Schneider: When I first approached Don, we decided to produce it together. We interviewed four or five documentary filmmakers, and with everyone we interviewed, we felt they were focused on the external story and wouldn’t be able to capture the internal story. We never felt that anyone we interviewed wanted to tell our story. They wanted to tell their story. But this was Don and I wanting to tell our story because we were there. So one day I said, “Don, why don’t you take it on?”

Filmmaker: Don, why did you decide to narrate the movie?

Hahn: We initially hired actors [to do the narration] and try different approaches. I did the narration as a temp track when we were putting the movie together, and in the end felt that my narration lent a more personal quality to the movie. I was trying to be a trusted voice leading you through the movie. In a funny way, [using myself as the narrator] led to me cutting myself out of the movie a bit more. The movie is not “the Don Hahn story.” I didn’t put what was happening in my life in the movie. I didn’t say, “I had my first child at this moment, and then I got this award.” Instead, I preferred almost being the voyeur, playing the role of the person who was taking you by the hand and leading you through the story.

Filmmaker: What during the making of this movie challenged your memories of this period?

Schneider: What challenged our memory was the discovery of the archive footage — when we found [animator] Randy Cartwright’s home movies [of work at Disney Animation]. Every three or four years with his cameraman, John Lasseter, 1980 went around studio filming things, just the heck of it. The discovery was finding all this footage in people’s shoeboxes and garages.

Filmmaker: Peter, what was the process of interviewing the subjects?

Schneider: We had [writer] Patrick Pacheco do preliminary interviews for us. He spent days and days interviewing 150 people. We sent him in as a kind of neutral person.

Filmmaker: Were these interviews on camera?

Schneider: No. We chose not to use talking heads — only archival and voiceover interviews. People were more honest if they weren’t on camera, and they were more relaxed when Patrick interviewed them. Patrick confirmed the story [we already knew] but he also amplified that story. It was out of those interviews that we built our movie. We used the words those interviewees said [while editing] and then Don went back and re-interviewed them for the movie. Our technique in making the movie was to tell you a story — like how they changed the title of The Great Mouse Detective and everyone going mad, and then cementing that story with an outside person, like, in that case, Alex Trebek asking a question about it on Jeopardy. We didn’t have footage of the standing ovation for The Beauty and the Beast at the New York Film Festival, but we had Roger Ebert talking about it. We used other people to confirm [our stories] so they weren’t just my word or Don’s word.

Filmmaker: What about the balance of the story, between the creative development of the films and the drama going on in the boardroom and executive suites?

Hahn: The balance of the story was always a contentious issue when making the film. Peter pushed more towards the executive story, and I wanted more balance from the artistic side. But this period of time unravels when the executive side unravels — that was the structure of the film. One leaves, one dies in a plane crash, and I had to invest enough time in [these figures] so you feel a sense of compassion.

Filmmaker: Do you think that culture that produced films like Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King has been lost? Or is it just different?

Hahn: I don’t know if lost is the right word. It’s changed. You can never strike a match twice. We had a young group of talented filmmakers who all then went their separate ways. The best thing that’s happened recently at the studio is John Lassiter being named the artistic leader. He’s bringing up a generation of new talent at Disney.

Filmmaker: What about the corporate culture, then? Has that changed?

Schneider: The corporate culture will always be there. Michael Eisner said, “You always have a boss of some sort.” [As a filmmaker] what you look for are executives and studio heads who understand your desires and are supportive, and that still exists. Brad Grey, Amy Pascal, Stacy Snider — they are all benevolent bosses. We executives are required to be partners because that’s what the system demands. You can argue whether that’s a good culture or a bad culture, but what has changed dramatically is the pressure of financing. The business was reasonable cheap to get into 25 years ago, and now these movies cost $200 million to make.

Filmmaker: Peter, how was the film’s depiction of your colleagues in the executive suites colored by your personal relationships with them before and after your tenure at the studio?

Schneider: I have great admiration for all three of the gentlemen — Roy Disney, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Michael Eisner. One of my goals [after leaving Disney] was to always be able to have dinner or lunch or fly on airplane with them. There are no bad feelings, and I still have lunch with Michael. In this story, none of them were villains, none were right, and none were wrong. They were all interesting, complex, and flawed human beings. The goal of the filmmaking was to not make them into good guys and bad guys, to make an “us against them” story. That would have been the easy choice. The truth is that without any one of the individuals we all wouldn’t have been as successful. There were thousands of people who made these movies and were integral to their success.

Filmmaker: Don, what was it like to change hats and make what is ultimately an intimate documentary instead of producing a huge animated film like The Lion King?

Hahn: Pretty great, mainly because of the speed and turnaround. Making animation is like steering an aircraft carrier. You are working with 500 people. It’s very gratifying, and it’s like nothing else in the film business, but this film offered different kinds of rewards. We worked with a small crew, just eight or nine people, and could sit at the Avid, make different choices, try things in multiple ways. Personally, this film has been a really great break for me.

Filmmaker: The film covers so many different personalities and events. What would you like people to take away from it?

Hahn: Emotionally, what I would love people to come see it for is Howard Ashman. He is hard to portray — he is articulate, he could have been a trial lawyer, he was the funniest guy around as well as a passionate and angry guy. I tried to share with the audience this nearly forgotten lyricist who was the catalyst, the creative guy who turned it all around. Executives may get the headlines, but you can point to Howard and say, “This is the guy who changed the world.”

Filmmaker: And you open on March 26?

Schneider: Yes. Disney is releasing it in five theaters. New York, San Francisco, Chicago. I hope it does business. Oddly enough, it’s opening the same day as [Dreamworks Animation’s] How to Train a Dragon. I’m trying to figure out how to spin it, to tie it in, but I’m sure Jeffery won’t want to do that.