Back to selection

Back to selection

Letters from Blocked Filmmakers: Michael Lew

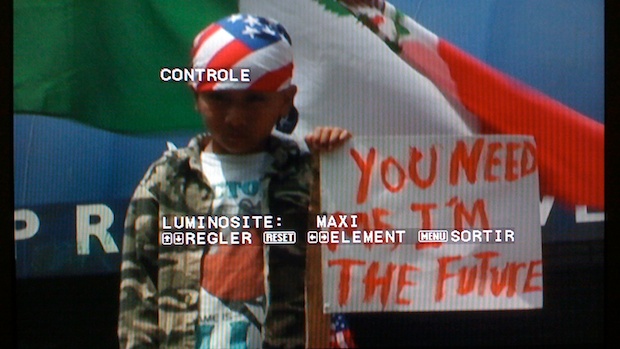

Junkyard of Dreams test shoot

Junkyard of Dreams test shoot Get together for drinks with a group of people who work in film, and soon the memories will flow. And they are usually linked to films these people have worked on. Film titles become markers of memory. It was on that film that this electrician met his future wife. On this one a P.A. adopted her dog. The sound guy was going through a divorce on this other one. The films may have faded from our collective memory, but the days on those sets are still ripe for the people who were involved.

In reading this letter from Michael Lew, I was struck by how unmade films function this way as well. In this autobiographical submission to “Letters from Blocked Filmmakers,” Lew places his stalled features on a continuum that stretches from his parents’ backgrounds through his childhood up until present day. The films he wants to make are expressions of his intellectual and artistic passions, and while the films are not made, he is clearly still immersed in their subjects. Another interesting note here: Lew’s films have attracted attention from labs like Film Independent’s, and Lew has attended various co-production workshops abroad. So, while U.S. indies often envy “the European system,” as Lew’s letter details, that system can be hard to break into as well. — SM

Dear Scott,

Today is Valentine’s Day.

I just started to rent a small room just above Lausanne, with a French flatmate who works as a nurse on night shifts in a private clinic. Instead of going to hit the bars and try to find some random lost souls, I decided to go back to my new room, assemble my new IKEA desk, and start writing to you.

Yes, since 2005, I have been trying to make my debut feature. With no success so far.

I come from a Jewish background. My grandfather was born in Warsaw, Poland, and his parents were killed during WWII. He met my grandmother in Vilnius and together they left to South America, where he was hoping to make a new life. There my father was born, who, when his mother died of cancer shortly after his bar mitzwah, decided to become a doctor. At the time they were living in Brazil, and the Zionist youth there sent my dad to Israel to learn Hebrew. There he started studying biology, and finally never returned to South America. He managed to continue his studies in Geneva, Switzerland, where he met my mother. My mother’s family was both wealthy — because of a tobacco business some uncles had built in the early 20th century — and diverse: art dealers, lawyers, bankers, scientists, engineers… And also a theater director from El Salvador, who had married my mother’s cousin. But above all, Switzerland proved to be a fascinating place to be, because of its neutral position in the world, its attempt to create the first League of Nations, its pharmaceutical industry, and all the NGOs in human rights based mostly in Geneva. The CERN for science, nuclear physics and the web, Piaget for saying that children would become a primordial subject of investigation, Rousseau and Voltaire, who posed the foundations of the French revolution, The Red Cross with Henry Dunant, the Rome of Protestantism with Calvin — all of these reasons and many more meant that I would grow up so happy to be from Geneva.

I spent the first years of my own life growing up in Boston, MA. So English in a way was my first language, including exposure to the media, kids shows on TV, public libraries, first tastes, scents and flavors. But the rest of my childhood and teenage years happened in Geneva.

I wanted to study something hard and solid, so I went for electrical engineering in the Federal Institute of Technology. I had been exposed to piano, harmony, acting and other things earlier, but there was no real established film school. After graduating, I went to New York to attend the New York Film Academy, and then was hired at MIT Media Lab in the interactive cinema group, between Dublin and Boston. I learned about the fundamental changes affecting media, and lived this tremendous revolution from the inside. In this climate of euphoria, I was hired to teach at USC in the new interactive media program. That was the year that my mother passed away, and it was a big shock to me. My mother. She had always been so close, and so overprotective. Through her, I lived her dream of living in Hollywood, meeting “famous directors and producers.” That was in 2004/2005.

At that time, I had recently met Chantal Akerman, in Jerusalem, where I had attended in parallel the first film festival dedicated to Palestinian film, and the Jerusalem film festival. You could really feel the line between the West, and the rest of the world, just by taking this little bus to Ramallah, after exiting the old city through the Eastern gate. There I saw Elia Suleiman, smoking a cigarette, who resembled a modern-day Buster Keaton, except that his country was under siege. Back in Jerusalem, Chantal and I spent an afternoon talking in a taxi, actually, that brought her to Tel-Aviv. She had just signed, for the first time of her life, a deal with a producer agreeing to make a film in Israel.

Of Chantal, I had seen a video installation in Rotterdam that portrayed the surveillance cameras around the border separating the US and Mexico. From there I started to investigate the topic. I spoke Spanish, and started to become acquainted with Latino culture, more specifically the Chicano world of Southern California. The Inca imagery, the gang stories, all that imagery started to blend and to reveal the life of these people, who were for the most part second-class citizens doing all the jobs that Americans didn’t want: in kitchens, shops, construction sites. I started to rent B-movies from a local video club that had this section with Spanish-only VHS cassettes. Speaking Spanish in the streets of L.A. gave me a little bit of warmth, the heartwarming feeling of being a refugee, an immigrant, sharing vulnerability and somehow also touching the vibrating strings of my Socialist and leftist sensibilities. Lenin had lived in Geneva, and Che was still a legendary figure.

So I started writing a feature film about the intertwining story of two characters: one young man from Central America, fleeing his home town to live his dream in L.A., and a sophisticated bourgeois bohemian PhD student from Paris, only wearing white shirts, coming to L.A. to study the “société du spectacle”: basically trying to deconstruct Hollywood and understand how it works. They are both from very different social classes. And the guy from Central America does not even have a precise goal in head, apart from making a living and having a stable situation. Initially he leaves his home country also because of gang harassment.

With this project, I was accepted into the Directors Lab program at Film Independent. That was amazing. I learned a lot. I met some people willing to help me, such as [producer] Ram Bergman for example. But my visa was expiring. I did not manage to find a job in L.A., and my attempts at getting a visa, or some kind of contract from a company that could get me a visa, failed. It was not an option to get married just for the visa, and I missed Switzerland. I felt I had learned enough for the moment to go home for a little while. When I hit my home base, the worst tornado in the financial world hit everyone by surprise: Madoff, Lehman Brothers, etc. I actually had to renounce any plans of going back to California for the time being.

I went to see a French producer (Dominique Barneaud) and went to all the information sessions in Cannes, Geneva, Zurich, Bern, about how to set up your own company and raise some funding to make your film. But my film, Junkyard of Dreams, had no European element, except the main actor, and me, the director, and some said that might not be enough to justify public money.

So I started to write a really low-budget film that could be shot entirely in Geneva. I called that film Blocages. Inspired by Albert Cohen and his time at the League of Nations, it takes place in the world of international organizations, in particular at the World Trade Organization. While the youngsters fight and demonstrate for a better world and for bottom-up fair trade, the old men representing governments of all sizes are confronted by the risks of war, instability, collusions with all sorts of traders and giant corporations — it’s quite ugly.

Picking up on this email now (on April 16th, 2013), I probably wandered off and did not answer your question. But at least I answered your call! I meant to write to you for a while. Yes, I have been stuck since 2006, approximately, not managing to make my films. I am now focusing on research technologies for a new kind of cinema, experimental video, some interactivity (as in video games in the tradition of cinema), but not too much.

I will hopefully be making a short film soon… and focusing on aspects of production design / set design as part of a PhD I have started in Switzerland, with the Zurich School of the Arts.

Anyway, I still hope to be able to make one day this film that I planned to shoot in Southern California and Central America.

I hope you are well.

Best wishes from Switzerland,

Michael Lew

If you would like to tell your story in this column, read the guidelines here and then email me your letter for consideration at scott@filmmakermagazine.com. — SM