Back to selection

Back to selection

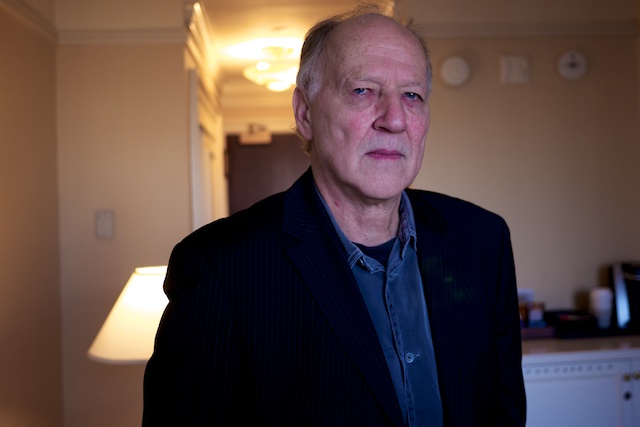

Werner Herzog on Into the Abyss

In his films, Werner Herzog has traveled the Amazon, journeyed to Antarctica and, most recently, descended through time into the caves of France to uncover centuries-old cave paintings. So, his trip to a small town in Texas awaiting the capital punishment of a young murderer might have been less epic were it not for the moral dilemmas, lingering anguish and genuine strangeness he finds there. Eschewing the tropes of typical capital punishment documentaries, Herzog, with his German-accented voice jutting from behind the camera, lends an empathetic ear to the words of not only the killer but his accomplice, the victims’ daughter/sister, his father, and several of the men responsible for his capture, incarceration and, ultimately, his execution.  There’s a prison chaplain who goes on a reverie about golfing and the squirrels who race across the course; a “prison wife” who reveals her own version of an immaculate conception; the victims’ relative, who describes entering and departing from years of intense solitude after the crime; and the accomplice’s father, who rues his own parenting skills from his own prison cell. And while Herzog gives us the details of the crime — a shockingly petty car theft that leads to the callous killing of a mother who opens her door to help two men in need — the abyss pictured here is a larger one, encompassing a culture in which violence functions almost like a virus, with men and woman both succumbing but also resisting its infection.

There’s a prison chaplain who goes on a reverie about golfing and the squirrels who race across the course; a “prison wife” who reveals her own version of an immaculate conception; the victims’ relative, who describes entering and departing from years of intense solitude after the crime; and the accomplice’s father, who rues his own parenting skills from his own prison cell. And while Herzog gives us the details of the crime — a shockingly petty car theft that leads to the callous killing of a mother who opens her door to help two men in need — the abyss pictured here is a larger one, encompassing a culture in which violence functions almost like a virus, with men and woman both succumbing but also resisting its infection.

The first of a series of films about capital punishment commissioned by Investigation Discovery, Into the Abyss opens today in theaters via IFC.

FILMMAKER: I want to ask you about this idea of a documentary with limitations. I understand you only had 45 minutes to interview death-row prisoner Michael Perry.

HERZOG: All documentaries have limitations. Let’s face it – every single film has limitations of time and money. You can ponder for five days over how to change a scene that doesn’t work, but on set, you have only 30 seconds. So every movie has these restrictions. In this case it was more severe. On Death Row there are strict rules. And there’s super-max security. You cannot change the rules, which is quite all right. You have to cope with it. That’s why we’re professionals.

FILMMAKER: One thing I liked about the film is that you let things be a little mysterious. Whether it’s about the exact events of the crime itself, or the paternity of the young baby at the end, you seem to allow situations to remain not entirely explained.

HERZOG: [In the film], I make my position clear. I respectfully disagree with capital punishment. But, as a German, I’m not telling the American people how to handle criminal justice. So please don’t expect that from me. I’m not interested in making a movie which tries to establish the innocence of an inmate. Yes, these films are wonderful achievements, like, for example, Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line, in which a man on death row was actually set free. But this film is something different. It’s more like American Gothic. A big tapestry. Innocence or guilt was, I think, beyond much doubt in the case of Jason Burkett. There was too overwhelming evidence. But I still allow [the two men] to at least maintain their innocence. I do not dispute it. I told everyone, “It’s not my business to establish guilt or innocence.”

FILMMAKER: You are creating a space for these people.

HERZOG: Yes, because it’s very gracious of them to let me talk to them in this capacity. Perry was going to die eight days later. However the hour or 50 minutes that I had with him, he really thanked me at the end, because for almost an hour he was almost completely oblivious to the fact that he was even in a prison. We talked about childhood adventures, canoe trips in the Everglades, alligators and monkeys. When you look at him, he’s oblivious that he’s on death row.

FILMMAKER: What do you think your interview subjects thought of you?

HERZOG: They all like me; because when you speak to someone on death row, they can tell from a mile away whether or not you are phony. And I’m absolutely blunt. Within 120 seconds of our conversation, I told [Perry], “The fact that your childhood wasn’t good doesn’t exonerate you. It does not necessarily mean that I have to like you.” And he froze for a moment, and I knew that my conversation could have ended right there. But they like me for being so blunt, so straightforward. They really like me for that.

FILMMAKER: In terms of this movie as a personal exploration for you, it’s called ‘Into the Abyss.’ Yes, the inmate is looking into the abyss. But –

HERZOG: – It’s us as an audience. We’re looking inside the deepest recesses of the human soul… Wherever you look there’s yet another abyss. It’s kind of mind-boggling.

FILMMAKER: Many of your docs are journeys of discovery. What did you discover in doing this film?

HERZOG: There are significant discoveries when you listen to the father of [Jason Burkett], who is in prison on a life sentence. The way he speaks about family values, about raising his children, it really sharpens your senses. I had become a bit dismissive of family values in Hollywood movies. They always prevail, and there has to be a happy ending. And all of a sudden, I look at it with completely fresh eyes. The way this man tragically speaks about how he should have dealt with his children; how he should have encouraged them to finish high school; how he should have avoided prison and been present as a father, I look at it with fresh, astonished eyes again. And the other thing I discovered comes from an inmate [in a different film in the series], who actually made the trip from death row to the death house. It’s a 43-mile trip to Huntsville, where they’re being executed. In 17years, he hasn’t seen anything of the outside world, and he describes this last trip in a van, caged in shackles with guards armed to the teeth. He’s traveling through a bleak forlorn part of Texas, and he says, “Everything looked like Israel. Everything looked like the Holy Land.” That really intrigued me. Later I did this same trip with my camera, and all of a sudden the world became magnificent. Even an abandoned gas station. All of a sudden yes, this is a Holy Land.

FILMMAKER: Are the other films in this series the same length?

HERZOG: No, they’re shorter. They’re one-hour programs.

FILMMAKER: Is each one exploring the particulars of a different person and case, or do they thematically look at the issue from different perspectives?

HERZOG: Well, they’re not finished yet, but I understand so far that it’s very multifaceted. Very different people end up on Death Row. Each of the films seems to have a different outlook, but at the same time they very intimately belong together.

FILMMAKER: I wanted to switch gears and ask you about your Rogue Film School.

HERZOG: I’m doing a new round this January in Los Angeles. Applications are open, but of course you have to be serious. What I want to know is – who are you? Rest assured that I read every single application and view every single short film. It’s my choice who I invite. But of course there’s more than this application. There’s a mandatory reading list, and it’s a serious list. It’s not just books on filmmaking. There’s Antigone. Virgil. Old Nordic poetry. Or a short story by Hemingway. Or the Warren Commission’s report on Kennedy’s assassination, which is a phenomenal piece of reading. I just try to hammer into each person, “Read, read, read, read.” If you don’t read, you will never be a great filmmaker.

FILMMAKER: How are you finding the students that you have? Are they becoming interesting filmmakers?

HERZOG: They are very fascinating people, without exception. And as I said, you do not need to have a staggering academic record. Sometimes I make my choice based on a five-minute film that’s not really that good, and I would normally dismiss it, but there’s a moment, a spark of incredible inspiration. And I invite that person, and I tell them, “This went wrong. This went wrong. But there’s this wonderful moment – hang on to it!”

FILMMAKER: It seems that the class must have its own critique of the way that other film classes are taught. It seems like it’s trying to do something different.

HERZOG: You’re allowed to speak about your perspectives, about your ideas, even if they’re only half-baked. If they’re fully baked, you don’t need to go to the Rogue Film School. And if you need to learn technical things, please just apply to your local film school. Rogue Film School is more about a way of life. I run this basically alone, singlehandedly. It’s very, very intense.

FILMMAKER: What are you reading right now?

HERZOG: A book which I should actually include on my Rogue Film School mandatory reading list. The Peregrine by a British writer, J.A. Baker, published in 1967 at a time when peregrine falcons were at the brink of extinction because of pesticides. This book, it’s only about the most meticulous, precise observations. It has such a passion for observation; it’s wonderful for every filmmaker. It’s one of the finest books I’ve read in a decade. The writer goes into such ecstasies that at some points in the book he starts off writing, “the falcon soars” and then switches to “we swoop.” He lapses into “we.” It’s very, very beautiful.