Back to selection

Back to selection

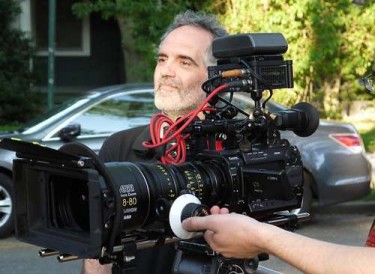

Dan Sallitt on The Unspeakable Act

The Unspeakable Act

The Unspeakable Act With an exacting intelligence, a hyper-articulate quality that brings to mind the characters of American systems novels, Dan Sallitt’s The Unspeakable Act meditates on the burgeoning mutual attraction of two Brooklyn siblings in a manner that, while leaving many unsettled, has already marked his third feature as a potential breakout for the critic-filmmaker. The scions of an old-school Brooklyn bohemian writer, Jackie Kimball and Matthew Kimball (Tallie Medel and Sky Hirschkron) have long harbored a forbidden desire for one another, although it is most intensely felt on Jackie’s side. Medel’s big green eyes under dark, foreboding bangs fill in all the gaps that the rapid volleys of voice over do not when it comes to the internal conflicts that this arrangement casts on her. Matthew, a bookish would-be scholar who prevents the situation from evolving into physical intimacy, soon leaves for college and Jackie is thrust into a crisis of sorts, stranded in the odd oasis of their mother’s almost otherworldly Brooklyn home. She seeks the help of a counselor, who may or may not hold the key to reigning in her incestuous impulses and allowing her to find an adult identity all her own.

The 57-year-old Sallitt is a Pennsylvania native who for years lived and worked in Los Angeles, where he cut his teeth as a critic for the Los Angeles Reader. He is the subject of an Anthology Film Archives retrospective that runs concurrent with the week-long release of The Unspeakable Act. Beyond his previous two features, 2004’s All the Ships at Sea and 1998’s Honeymoon, the retro will feature a rarely seen, mid-80’s, feature length video experiment titled Polly Perverse that Sallitt made while in conjunction with the long defunct L.A. video-art gallery EZTV.

The Unspeakable Act opens this Friday.

Filmmaker: All three of your films primarily deal with the complications of a single familial relationship and the ways unusual upbringings both trap and offer a way out for the characters. Where does this set of concerns come from within you?

Sallitt: If it’s autobiography, I don’t realize it. I love making films about family, because you can show the strangest, most dissonant behavior and still remain well within the bounds of the everyday. The trap and the way out…that’s an interesting way to put it. Recently I’ve started to notice that my films are pretty Romantic under a veneer of naturalism: there’s always a character who does extraordinary, almost fantastic things. I thought I’d left that stuff behind with my childhood, but no.

Filmmaker: Perhaps this dynamic is taken to a new level entirely given the forbidden intimacy that’s at the heart of The Unspeakable Act.

Sallitt: I guess that the trap, to use your phrase, is right up front this time, the first thing the viewer sees. On the other hand, maybe that makes it possible for the rest of the film to be relatively gentle. My last movie, All the Ships at Sea, is also about unrequited love between siblings, but in that case the trap is constructed slowly and is fully visible only at the climax.

Filmmaker: Does being a critic inform how you write movies at all?

Sallitt: Two things happen simultaneously, or in very quick alternation, when you write a script: one side of the brain generates the ideas, and the other side shapes them. The generation of the ideas is a crazy, infantile business that has nothing to do with criticism, or really even with art. But the shaping draws on exactly the same skill set and experience as does criticism: in that mode you’re being your own critic.

Filmmaker: Given how dramatically the low budget and microbudget film landscape has changed since you last made a feature in the early aughts, was it more or less challenging to put together from a practical and financial standpoint then the others?

Sallitt: I’ve always financed my own movies, so I’m blissfully shielded from the fundraising aspect of filmmaking. Each film costs a little more in some ways and a little less in others – I’d say costs are holding steady overall, while benefits are increasing. For instance, I pay less for lighting equipment because cameras are more sensitive to light, and the overall result is superior.

Filmmaker: Did you write it for with the performers in mind or was there a prolonged casting process?

Sallitt: The latter. When I wrote this script, I didn’t have an intimate enough connection with any young actor to customize the lead roles. I find casting very hard and very scary: I started casting nine months before the shoot, and even so there were key parts that I didn’t nail down until the last minute. But I really lucked out this time around.

Filmmaker: The Unspeakable Act has an immaculate and considered visual style, which I imagine was achieved on a low budget. How did you discuss the intended aesthetic with your collaborators and what were the most key elements to give it the texture it has?

Sallitt: The director of photography, Duraid Munajim, had worked with me twice before, and he had a pretty good handle on what I wanted. The first time he shot with me, I told him I wanted the lighting to look like Nestor Almendros, and I gave him a copy of A Man with a Camera to read. I think I recommended Claire’s Knee and The Marquise of O… as references. That kind of lighting is not necessarily expensive, and with today’s sensitive cameras it can often be done quickly.

The compositions are pretty much my department, and I stick close to my storyboard, which contains little detail but which shows blocking and the amount of space around the subjects. The storyboard is also a cutting continuity, and the final cut is extremely close to what I put on paper. Bridget Rafferty, the production designer, had a lot of freedom, and then the actors and I would sometimes ask for small changes on the set. The amazing house that we shot in was another stroke of luck, and we had no budget or permission to change the color scheme that it imposed.

Filmmaker: How do you know when you’re ready to shoot a scene? Do you rehearse things until you think it’s perfect or do you prefer the chaos of takes that may come from the performers and the crew feeling less sure?

Sallitt: I greatly dislike chaos, and put lots of directions for cast and crew down on paper. But in recent films I haven’t done much rehearsal, and it’s amazing how often the first take of a scene contains original acting that can never be duplicated. Then I fuss over the performances, and after multiple takes we arrive at something that may be better or worse than what we started with. In the editing room, sometimes spontaneity wins and sometimes calculation. In future, I plan to do more rehearsal before shooting certain special scenes, like emotional moments that are physiologically difficult to repeat.

Filmmaker: What most surprised you about the nature of the movie you were making once you got to the editing room?

Sallitt: I knew on the set that Tallie Medel was terrific, but I didn’t fully realize how astonishing that performance is until I sat with it in the editing room. During shooting I can be a little too focused on the broad outline of things, making sure that meaning is conveyed and that mistakes are eliminated. But during editing I can relax, put my antennae out, fully appreciate the vibrations of performance. Quite often I don’t use the take that I’d thought was best when I was shooting.

Filmmaker: Are there ever any regrets you carry into the night about this film (or the others)? Things you felt you could have done differently, or better?

Sallitt: Oh, there are always regrets, and you have to accept that as part of the process. Each time out I get a little smarter about how to set things up to avoid pitfalls, and each film I’ve made has fewer things that I want to change than the last. Every misgiving that I’ve mentioned in this interview – my rehearsal habits, my relative insensitivity to acting nuance on the set – has already given rise to remedial strategies. Still, eliminating imperfections isn’t necessarily the most important thing about filmmaking. A crude early work can be more moving than a refined later one. You just have to move on and leave it for others to decide.