Back to selection

Back to selection

Hirokazu Kore-eda on Still Walking

A connoisseur of longing and remembrance who brings great sensitivity to each of his reflective fables, Japan’s Hirokazu Kore-eda should be better known in the States, as his films extend the tradition of world-class artists like Naruse and Ozu. Enthralled with the operation of memory and the impact of grief on the lives of everyday people, Kore-eda has created a body of work that’s as rich with feeling as it is modest in tone. In Maborosi (1995), Kore-eda told the story of a quietly devastated young widow struggling to move on after her husband commits suicide. He then departed from this film’s elegant compositions and moody, color-saturated production design to draw on the observational techniques he’d developed earlier in his career as a documentary filmmaker. After Life (1998), built around interviews he conducted with hundreds of participants, visits an institutional purgatory where the recently deceased are asked to choose a single recollection to relive for eternity as a film. Distance (2001) and Nobody Knows (2004) are both loosely based on high-profile news items: the emotional aftermath of the Aum Shinrikyo sarin-poisoning tragedy and the heartrending story of three school-age children who survived for 200 days in an apartment after being abandoned by their mother. Even Hana (2006), an Edo period piece, has none of the usual trappings of the jidai geki genre, instead emphasizing the gentle, domestic rituals of a reluctant samurai-turned-village teacher who elects not to avenge the murder of his father. Throughout these films, Kore-eda studiously avoids the pitfalls of cynicism and sentimentality, exploring the private worlds of vulnerable, emotionally complex people with extraordinary grace and subtlety.

If Kore-eda is deeply attuned to the mystery of memory and the inner lives of those grappling with loss, he is also attentive to the subtle rhythms of family life, which he captures in an unobtrusive, naturalistic style. His latest feature, Still Walking, surveys a low-key family gathering at the home of proud, retired doctor Kyohei (Yoshio Harada) and his wife Toshiko (Kirin Kiki), who have assembled their relations to honor their eldest son, a drowning victim, on the occasion of his death. Surviving brother Ryota, an art restorer, has recently married Yukari (Yui Natsukawa), a 40-year-old widow with a preteen son (Shohei Tanaka), and is wary of Kyohei’s gruff judgments about his life and chosen career. Chirrupy sister Chinami (pop star/TV personality YOU), happily married with a small brood herself, keeps the mood light even when kitchen-table conversation turns sour. Over the course of 24 hours, as long-simmering tensions bubble to the surface, the atmosphere remains tinged with plaintive regret and flecked with wry, true-to-life humor. Kore-eda gives each of his characters full-blooded life as we glimpse each of them in private moments. Though it carries echoes of Ozu’s Tokyo Story in terms of its general themes and domestic scenario, Still Walking is gentle in its aims, comforting even in its moments of discomfort, and graced with earthly images of transcendence (flower blossoms, a child’s hands). By the end, we’re privy to a poignant farewell that carries the notion of life as a cyclical and honorable journey.

IFC Films opens Still Walking Friday in select theaters.

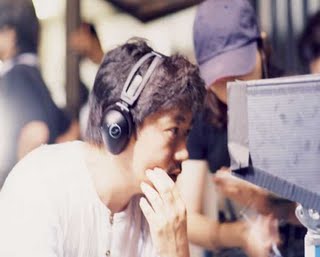

TOP OF PAGE: [LEFT-RIGHT] YOSHIO HARADA, SHOHEI TANAKA AND KIRIN KIKI IN STILL WALKING. ABOVE: STILL WALKING WRITER-DIRECTOR HIROKAZU KORE-EDA. PHOTOS COURTESY OF IFC FILMS.

TOP OF PAGE: [LEFT-RIGHT] YOSHIO HARADA, SHOHEI TANAKA AND KIRIN KIKI IN STILL WALKING. ABOVE: STILL WALKING WRITER-DIRECTOR HIROKAZU KORE-EDA. PHOTOS COURTESY OF IFC FILMS.Filmmaker: You mentioned in your director’s notes that Still Walking grew out of a personal experience, specifically the sense of regret you felt after the death of both your parents. Could you elaborate on that and say how this experience fed into the concept of the film?

Hirokazu Kore-eda: [long silence] My mother had breast cancer but continued to live alone after my father passed away. I would phone and e-mail her occasionally, but I really left her on her own. I was working on Nobody Knows at the time, so I was very busy, and I used that as an excuse and didn’t go see her very much. Then I had a dream in which my dead father called me on the phone. It was very much like the relationship between the father and son in Still Walking: We were on the phone but had nothing to talk about. Finally he said, “I’m calling about your mother.” And I said, “Oh, I just talked to her yesterday, she seems fine.” And my father said, “No, she’s not fine. I think it’s going to happen around the 28th.” I woke up thinking, “What is this, the 28th?” I didn’t want to take it literally, so I ignored it. The morning of the 29th is when she had to be hospitalized, and I felt incredibly guilty. Even though my dead father came to tell me that in a dream — which is not the sort of thing I actually believe in — I still didn’t go home and see my mother. After she was hospitalized, because of my guilt, I spent a lot of time with her. But it really was too late. At that point, I started regulating my work a little bit and seeing her more frequently. My older sister and I kept notes on conversations we had with her, and in the two years my mother was ill, before she passed away, we were able to catch up and talk about all these things that in the 15 years prior we hadn’t really discussed. Her dementia was getting worse, but she’d recall things about my childhood, the home we lived in, the tempura we used to eat — things like that. At her death, my sister and I had a total of five notebooks from all the conversations we’d had over those two years. We looked it over and that was a starting point; that was my material for writing this screenplay.

Filmmaker: You have a quiet and dignified approach to representing this family, and yet over the course of the day, the fault lines in their relationships come to the surface. There are a number of tensions in the film, between the domestic and public spheres, between men and women, youth and age. Did you have these in your mind while writing the script?

Kore-eda: I was very aware of those tensions as I was writing the script. It’s basically a social rule that you don’t say what you mean to the person that you feel [tension with], and that’s true of my mother, of me, and of most of the people around me. You don’t say what you think to their face, and then you go to someone else and say what you really think. There’s a disjointed line of communication, so that’s something I was conscientiously working with.

Filmmaker: As a filmmaker, you’re very attentive to gesture and nuance, and the subtle ways that people relate to each other. How do you maintain the balance between action and nonaction, between the things that are said and those that are left unsaid?

Kore-eda: [long pause] That’s a difficult question.

Filmmaker: Well, I could rephrase that by asking, do you write or direct certain scenes that you decide to remove because they interfere with the capturing of those nuances?

Kore-eda: There are definitely times when I’ll shoot a scene and edit it out completely later, and sometimes I’ll go in and add things as we’re going along with the shoot. For example, with this movie, there isn’t a story or plot that needs to move to a certain place. The top priority was portraying a single day in the most naturalistic way possible. Of course, we had the character relationships and the character premises before we started the film. But with Yukari, who is the new wife to the second son, she’s a person who’s in the most difficult and oppressive situation. She has to really hold her tongue and be smiling all the time. And as we were working, I could see that her character was going to want to remove herself at some point and be alone. So we have the scene where she’s alone [in a bedroom], and when her husband comes in, that’s when she says what she really thinks. And that’s something we could see as we went along.

Filmmaker: Do you think you achieved something new with Still Walking in terms of behavior and emotion?

Kore-eda: I think with this film, more than any other, I was able to portray the most sides of a character — to show their complexities and in the most well-rounded, three-dimensional forms. For example, in making Nobody Knows, of course I was involved with the children, but as a director I worked mostly from a detached point of view and didn’t really get involved with their inner selves. It was [shot] almost from a documentarian point of view. In this movie, [in terms of] my relationship to the characters, the distance was much closer.

Filmmaker: I ask you that because I see you working through and revisiting the same themes in so many of your films: death and mourning, loss and remembrance. I wonder if you’ve reached a point where you have realized those themes in a way that makes you want to think about exploring something else, or whether you think they will continue to be a persistent contour of your work.

Kore-eda: [laughs] Well, in terms of those themes you see recurring, that really happened very unconsciously for me. In a way it’s a big problem. If it was a conscious choice on my part, it’d be easier to understand. But I have to say that with my next film, Air Doll, I conscientiously depart from some of my previous themes. It’s very different in terms of its main motifs and ideas. But I think as time goes on, my personal interests will change, my environment will change, and also my technique will evolve.

Filmmaker: Nostalgia is important in Still Walking, too. What’s the story of “Blue Lights of Yokohama,” the song that has such a strong resonance for Toshiko in the film?

Kore-eda: It’s a song my own mother really loved, and it played a lot when I was in elementary school, so it always left a very strong impression on me. I always wanted to use it in a movie. The original Japanese title [of Still Walking] literally means Keep on Walking, Keep on Walking, which are direct lyrics from the song. I thought at some point in the movie I would make a scene where that song is played. It was a backwards process to do it that way, but that’s where the song came from. There are a lot of mysteries left in the movie, actually, and some stones are left unturned because the scope of the film is limited to that one day. For example, there’s someone who’s left flowers on the grave of the older brother. You don’t know who it is and you never find out — it’s outside the scope of the film. Then some things happen that other characters don’t know about: Atsushi talks to his dead father in the dark yard, but the main character, Ryota, doesn’t know that. When you have some mysteries left behind, even after a movie is done, it makes for a richer world and a richer film. Some things that are deeply hidden — emotions the mother has or an allusion to adultery on the part of the father — are left unexplored by the end.

Filmmaker: Do you think in general you strive to hark back to the Japanese cinema masters of the past in creating films?

Kore-eda: I definitely think there’s a lot I can learn from that era, but I don’t have any desire to go back to that. By the time I started working as a director, the studio system was long gone, completely dismantled in Japan, so I never had it in mind to work in that kind of environment. When I started out, the people whose works I found more helpful to reference were contemporaries who were working in the same situation as me, not the studio system, people like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Víctor Erice, from Spain. Of course, there are Japanese masters like Ozu and Naruse who dealt very much with the Japanese family. The environment they worked in is very different from mine, but in terms of how they portray the Japanese family and domestic sphere, I had much to learn from them working on Still Walking.

Filmmaker: While your films seem utterly contemporary, I could not help but think of Ozu at certain moments in Still Walking: there are those elevated shots of Yokohama with the commuter train running through the frame, and one of a potted flower in a darkened room that reminded me of a similar shot in Late Spring. I like those little homages and wondered how much they were in your mind.

Kore-eda: [smiles] Thank you very much. But it’s something I really wasn’t conscious of while I was working on the film. Now, those examples you brought up make me think — oh, a flower in a darkened room, I’ve definitely seen that before! [laughs] And as soon as you mention it, it makes a lot of sense to me. Honestly, I was not conscious of it, but thank you.

Filmmaker: Originally you had ambitions to be a novelist, so what was it about film that for you became the best forum for self-expression?

Kore-eda: I don’t know. I might find out that maybe film is not my medium! [laughs]

Filmmaker: I doubt that very much. You still write, don’t you, for magazines?

Kore-eda: Yes. I still like to write. Sometimes, if you ask me do I prefer writing or shooting, I might say writing. [laughs] These days, I’m not certain it’s exactly right for me. I’m not joking when I say this, I’m not totally sure this is what I was meant to do. In my late teens, when I started to going to college, I was in a literature department at university and my classes were so boring. I started going to a movie theater every day. There used to be a theater in the Ginza district, and it was a really stinky basement theater that had maybe 40 seats. One Sunday, they had a double feature of Kurosawa’s Ikiru and Wonderful Sunday. And at the end of the second movie, the people in their seats all got up and applauded, even though there was hardly anybody there. Maybe everyone had a different reaction to what we saw, but there was a sense we had a communal experience together. And that communal feeling was something I got really hooked on. Up until that point, I was a really independent person. I liked to read by myself and write, and I didn’t want to get involved with other people. After that experience, the joy of sharing things with other people really struck me.

Filmmaker: You alluded earlier to the fact that your techniques have evolved over the years, and I certainly notice an extraordinary stylistic gap between the lush formalism of Maborosi and the later work, like Nobody Knows and Distance, where you are drawing more on the documentary techniques that you had worked with previously in television. I wonder where you see yourself in that process now. Where is your technique evolving on Air Doll, for instance?

Kore-eda: When I made Maborosi, up until then I had only worked in TV, so I really wanted to make a movie, you know? I had a very strong desire to make a film and I was very aware of what a movie is. As time has passed, I’ve lost that sort of self-consciousness about what a movie might be or should be. In terms of making Still Walking, the only problem I had was, “How do I portray a single day and people and their lives in the most realistic and naturalistic way possible?” I never thought, “Oh, well, it’s a movie so it has to do this,” or, “How can I use the medium of film to do that?” I just wanted to portray people honestly instead of “making a film.” So that’s definitely changed over time. But you’ll see with Air Doll that I’ve taken a completely different approach, so it’s continually evolving. This is a story from long ago, but 15 years ago, when I had just finished Maborosi. I was doing an interview on TV, and I was able to meet Hou Hsiao-hsien and I got him to watch Maborosi. He said to me, “Your technique is great. But I can tell that before you started shooting, you storyboarded everything. You did, didn’t you?” And he said, “How do you know how you’re going to shoot a person before seeing that person? You started in documentary, so you should know that better than anybody.” It left a very strong impression on me. After that, I stopped doing storyboards. We’ll get to a location now and we’ll do a little rehearsal, and I’ll see how things flow. I’ll look at the people and then decide where to place the camera. Because of that one comment from Hou Hsiao-hsien, I’ve changed my approach. And not just my approach to filmmaking but also how I deal with people in general, in life. So I think I’m still in the process of working on what he’s taught me.

Filmmaker: Incidentally how do you see the landscape for independent cinema changing, or how has it changed in the past few years in Japan?

Kore-eda: The future is very dark! [laughs] One thing that’s happening in Japan is all the arthouses that show more artistic and foreign films are all going out of business. They’ve been replaced by multiplexes all over the country, which only show Hollywood films, commercial films. They really don’t want to show films from Europe or other places. These arthouses can’t financially survive anymore. For independent filmmakers like myself, the films themselves can’t survive off ticket revenues, so you can’t have long runs. For example, Maborosi came out 15 years ago, and it was in the theater for 16 weeks. Still Walking, which was pretty popular, was only in the theater 8 weeks. One other thing that’s happening now is that I’m not sure you can even say the films we’re watching are even all films. For example, TV dramas will have 11 episodes air on TV, and if it’s a big hit, they’ll call the season finale a “movie” and put it in theaters. And that’s not really a movie. So for independent filmmakers in Japan like myself and Kiyoshi Kurosawa, it’s a survival game. I don’t have a lot of hope for the future right now, but we’re going to work hard.